Page index

This is a series of articles in Canada's National Post dealing with forced adoptions of babies taken from their single mothers at birth.

- Curtain lifts on decades of forced adoptions for unwed mothers in Canada

- Taken without mother’s consent: Woman calls for inquiry into P.E.I.’s ‘systematic removal’ of children

- Coerced adoption: Salvation Army launches review of maternity homes that housed unwed mothers

- ‘The fathers had no say’: Men tell another side of coerced adoption story

- ‘These women didn’t know their options’: Ontario urged to consider inquiry into coerced adoptions

- ‘You suffered just as much’: Adoptees gain new insight into parents’ choices as coerced adoption stories come to light

- B.C. government hit with class-action lawsuit over coerced adoption claims

- The Australian precedent: Women fighting for an adoption inquiry look across the ocean

- NDP MPP Monique Taylor ‘shocked’ at lack of response to push for coerced adoption probe

- Senator joins growing call for probe into forced adoptions

- Your baby is dead: Mothers say their supposedly stillborn babies were stolen from them

- What the #!%*? Is anybody investigating the allegations of forced adoptions across Canada?

- United Church archives ground zero in search for evidence of forced adoptions

- United Church of Canada to hold mirror to its role in forced adoptions as families push for national inquiry

Curtain lifts on decades of forced adoptions for unwed mothers in Canada

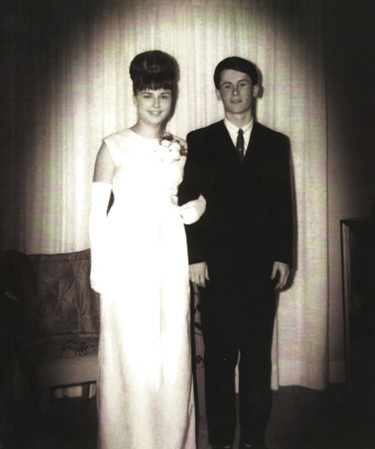

Karen Lynn was 19 when her mother sent her to a home for unmarried pregnant women in Clarkson, Ont., in 1963. There, she was known as Karen No. 1 to protect her family’s reputation, and said it was clear she would not have been allowed to stay there if she did not agree to an adoption. A year later, Sharon Pedersen was 20-years-old when she was drugged and tied to her bed during labour and then shown four different babies through the nursery window at a hospital in Victoria, she said.

She ultimately signed adoption papers at the local children’s aid society, she said, but not before social workers held a pen in her hand and threatened to call the police because she was screaming and throwing furniture in protest.

Similar accounts have begun to emerge across Canada, and there is now a growing movement calling on the federal government to probe this country’s historic adoption practices. Many decades have passed, and many women have since reunited with their sons and daughters, but they are speaking out against what they say were coerced and forced adoptions.

Not every unmarried mother was coerced or forced into giving up her child, but the women going public today are not alone.

Their stories sound eerily like the hundreds of testimonies submitted to a recent Australian inquiry into adoption from the 1950s to the early-1980s, and last month an Australian Senate committee urged the government to apologize to the “many parents whose children were forcibly removed” from their care.

Beyond a push for an inquiry here, Canadian provinces from Quebec westward will soon be hit with class-action suits accusing the governments of kidnapping, fraud and coercion, according to the well-known lawyer heading the pending actions.

“Clearly, this story is a sad and difficult one, and we’re just beginning to hear more about it,” said Bruce Gregersen, a spokesperson for the United Church, which co-ran Winnipeg’s Church Home for Girls, where one woman said she was told she could be criminally charged if she tried to keep her child. “This will warrant a great deal of attention.”

Seven women spoke with the National Post, most telling their stories openly for the first time, in the hopes of airing what some say was more than a vague societal push for unmarried mothers to consent to adoption.

Teenaged and unmarried, Valerie Andrews said she was unknowingly given medication to block her breast-milk. Hanne Andersen said her B.C. hospital records say “Baby for Adoption” even though the teenaged single mother had planned to keep the baby. Social workers in Sudbury, Ont., never told Esther Tardif she was eligible for social assistance and said if she loved her unborn child, she would let him go.

Most of the mothers interviewed for this story said the coercion was systematic: From the church-run maternity homes where accommodation was sometimes predicated on adoption and where mothers had to write a letter to their unborn child explaining the separation; to the social workers who concealed information about social assistance and who told single mothers they could be charged with child endangerment; to the medical staff who called the women “sluts” and denied them painkillers, and who reportedly tied teenagers to their beds or obstructed their view of labour with a sheet.

“To the Canadian establishment, this will come as a big surprise,” said Ms. Lynn, who heads the Canadian Council of Natural Mothers, which aims to expose the negative treatment of mothers in adoption practice. “What we hear all the time is, ‘You gave up your baby.’ What I say is that, at very best, it was a tragic choice.”

Ms. Andrews has studied Statistics Canada data on illegitimate births from 1945 to 1973 and the rough rate of adoption among unmarried women at the time, and offers what seems to be an astronomical estimate: that 350,000 unmarried Canadian mothers were persuaded, coerced or forced into adoption.

But some unmarried women may have been grateful to know their child would grow up in a secure home and spared the stigma of being an illegitimate child, said Lori Chambers, who pored over thousands of archived children’s aid cases for her book, Misconceptions, about unmarried mothers in Ontario from 1921-1969. And not all ostracized women suffered in maternity homes — some would have appreciated the shelter, food and friendships that no one else would provide.

“The question becomes not why unmarried women gave babies up for adoption, but how some women had the fortitude not to,” Ms. Chambers said. “Most of them gave up and released their child for adoption.”

Ms. Andrews has spent much of the past four years documenting the treatment of unmarried teenaged mothers in church-run maternity homes, hospitals and children’s aid societies, at a time when abortion was illegal, birth control was not easily accessible, and unmarried mothers were seen as loose women too feeble-minded to parent.

Joyce Masselink, a social worker who dealt with unmarried single mothers in Toronto and B.C. in the 1960s, said Ms. Andrews’ estimate “does not sound realistic,” and said girls were “treated very well” in the church-run maternity home she often visited in Vancouver.

When Marilyn Churley found herself alone and pregnant in 1968, the former Ontario MPP said her social worker in Barrie, Ont., was the only friend she had — although she said the social worker never talked about alternatives to adoption and that she endured a “horrific” 24-hour labour without painkillers.

“I didn’t know any social workers who forced or coerced women into adoption, and I certainly didn’t myself,” Ms. Masselink said, adding that some social workers were, however, rigorous in promoting the social values of the day. “I do know that probably went on, though. Women’s stories attest to that.”

An April 25, 1961, Ann Landers column perhaps best illustrates how society viewed unmarried mothers. In describing a single mother’s love for her child, she wrote: “Such ‘love’ is questionable. It is a sick kind of love turned inside out — an unwholesome blend of self-pity mixed with self-destruction and touch of martyrdom.”

Most of the mothers interviewed for this story said they kept their secret for decades, having been “groomed for shame,” Ms. Andrews said. But with last month’s Australian report, the women said it is time for Canadian mothers to know they are not alone and for their children to know they were not unwanted. Ms. Andrews has planned a two-day conference airing Canada’s history of adoptions this fall in Toronto, and is hopeful hundreds of mothers and adoptees will attend.

The Australian committee called on the government to apologize — without reference to the social values of the day — and to compensate mothers, some of whom “recounted a pregnancy marred by systematic disempowerment,” according to the report.

“I still feel the shame,” said an Ontario woman named Katie, who asked that her last name not be used because her daughter does not know she was conceived in rape. “It wasn’t until I got my hospital records and saw what they did to me that I could start breathing without this horrible weight on my shoulders.”

Katie said she was given labour-inducing drugs and was not allowed to hold the child at a Winnipeg hospital, not far from the United Church home where she was living. The fair-haired 17-year-old was knocked out with what “felt like a chemical straight-jacket” and later shown a black-haired baby who was too big to be a newborn, she said.

Katie said she never signed an adoption paper but remembers nodding in a courtroom where she thinks she made her daughter a ward of the state.

Ms. Chambers said until Ontario children’s aid societies started receiving substantial government funding in 1965, they relied mostly on donations, often from adopting parents. She said the societies were in a conflict of interest, then, and at times struck a deal with the father: If he consented to an adoption and paid a small sum, the society would not represent the woman in a costly child-support battle.

Ms. Andrews, who heads Origins Canada supporting people separated by adoption, is urging the federal government to follow Australia’s lead and launch an inquiry here. She said roughly 100 mothers and adoptees have so far registered with the organization for a future inquiry, but said Justice Minister Rob Nicholson’s office told her this is a provincial matter. A spokesperson for the minister confirmed this is the government’s position.

Ms. Andrews said a July, 2011, letter written by her Ontario MPP, Reza Moridi, to the Minister of Children and Youth Services has so far gone unanswered.

“Nobody will acknowledge this because they don’t believe us, just like for years they didn’t believe the women in Australia,” said Ms. Andersen, who today heads Justice for Mother and Child, an advocacy group for those “unlawfully separated” at birth.

She plans to file a police report this month to prompt an RCMP criminal investigation into women she said were “targeted” for their babies, many of whom were white, healthy and in high demand, she said. Ms. Andersen, who became pregnant at age 15 in 1982 and said she was allowed to hold her baby just once, will also be the lead plaintiff in a class-action suit expected to be launched against the B.C. government in the coming weeks or months.

“My feet were still in stirrups and I had a sheet over my body so I couldn’t see the baby,” said Ms. Andersen, who claims her consent to adoption was invalid because she said she never actually had possession of her daughter in the first place. “They wrapped her up in a blanket … I said, ‘Stop! Where are you going with my baby? I asked three times and had to yell, ‘Bring me my baby now!’”

A draft of the statement of claim says the class action will cover women affected by the “Baby for Adoption (BFA) protocol” and seeks general and special damages for the lost opportunity to parent, medical treatment without consent, and mental distress.

“I don’t think there is any question there was a policy where, if a child was born outside of a marriage, that child was not to remain with the mother,” said Ms. Andersen’s well-known Saskatchewan lawyer, Tony Merchant, whose firm secured a $2-billion settlement in the 2006 Indian Residential School class action.

In Australia, the inquiry heard the “BFA” policy often led to treatment in line with the then-popular “clean break theory,” which said it was in everyone’s best interest to avoid contact between the natural mother and her child after birth.

A spokesperson for the B.C. Ministry of Children and Family Development said ministry staff “don’t know of any concerted policy in the government back in the 1960s and 1970s that would have forced women to give up their babies.”

Mr. Merchant said the class-action suits will attempt to saddle the provinces with responsibility for the wrongdoings of church-run organizations because they were provincially funded agents.

John Murray, a spokesperson for the Salvation Army, said the government-funded maternity homes it ran — such as Maywood, the B.C. home where Ms. Andersen said she was starved, verbally abused and never told of any available social assistance — helped pregnant teens in a time of need.

“I can’t specifically comment on how the organization managed its operations 40 or 50 years ago,” said Mr. Murray. “That’s not to say there weren’t perhaps isolated situations … but certainly, I think historically the Salvation Army was welcomed and valued by people in the community.”

A spokesperson for the Presbyterian Church in Canada, which owned the maternity home where Ms. Lynn stayed, said “there’s no one here now with any kind of living memory of what went on 40 years ago.” The Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops said it is up to each specific diocese to comment separately. Neither the Canadian Medical Association nor the Canadian Pediatric Society would comment. The Ontario Association of Children’s Aid Societies passed an interview request to the Toronto Children’s Aid Society, which did not respond to a separate request for comment.

Mr. Gregersen, meantime, said the United Church will now comb through its archives to find out what happened at its maternity homes, but said he invites mothers to come forward so researchers know where to focus their efforts.

“Canada is so far behind on this,” said Ms. Pedersen. “I’ve been breathless ever since the Australian report came out. It’s about time it was acknowledged that these were forced adoptions.”

Source: National Post

Taken without mother’s consent: Woman calls for inquiry into P.E.I.’s ‘systematic removal’ of children

A woman is urging the Premier of Prince Edward Island to launch a public inquiry into that province’s historic adoption practices, which she said resulted in the “coercive and systematic removal” of children from their unmarried mothers from the 1950s to the 1970s.

The call comes ahead of an expected series of class-action lawsuits against provinces from Quebec westward, accusing the governments of kidnapping, fraud and coercion, according to Tony Merchant, the prominent lawyer heading the pending actions.

“There is evidence that unethical and improper procedures were widespread,” Mary MacDonald, who was adopted in 1958, wrote in a March 5 letter to P.E.I. Premier Robert Ghiz. “The activities and involvement of religious agencies in co-ordination with government and judicial agents is a collective shame that rivals the scandal of the residential school system.”

Ms. MacDonald said her adoption records show a government-certified adoption agency, which she said was run by Protestants, took her from the hospital before her mother signed a surrender document. She said the document was later signed but was neither witnessed nor notarized, and that the lawyer handling the adoption was simultaneously sitting as chairman of an orphanage.

Ms. MacDonald said the Premier has not yet responded to her letter, which came on the heels of an explosive February report by the Australian Parliament calling on the Australian government to apologize to the “many parents whose children were forcibly removed” from their care. Mr. Ghiz’s spokesperson did not respond to an interview request on Sunday.

The P.E.I. woman is among the growing movement of mothers and adoptees calling on the federal and provincial governments to probe this country’s adoption practices, during a time when abortion was illegal and unmarried mothers were stigmatized as feeble-minded and unfit to parent.

On Saturday, the National Post told the stories of several women who said they were coerced or forced into putting their babies up for adoption between the 1950s and the 1980s — whether by social workers who threatened women with police action unless they consented, by matrons at church-run maternity homes who said unmarried women could not live there unless they agreed to an adoption, and by medical staff who denied women the right to hold their babies and reportedly gave them lactation-suppressants without their knowledge.

Over the weekend, more than a dozen other mothers contacted the newspaper with similar accounts of systematic coercion, and at least three said they are seriously considering joining any future class-action lawsuit against the Ontario government.

“As far as I’m concerned, young women were wronged, and choices were taken away from them,” said Betty Meredith, who was sent to an Ottawa maternity home for unmarried mothers when she was 18 in 1964. “To this point, no one’s paid too much attention to the suffering of these mothers.”

Ms. Meredith said she signed adoption papers before her daughter was born — before she was tied down to the birthing table, covered with a sheet so she could not see the baby being born and then unknowingly given drugs to dry up her breast-milk.

“This has nothing to do with money,” said Jani Francis, who also plans to join the Ontario class-action suit after her experience as an unwed pregnant teenager in Toronto in 1969. “What happened was cruel and inhumane. I want someone to be held responsible.”

Ms. Francis said she signed a temporary wardship putting her son in government care for three months so she could buy herself some time to find a place to live. Her parents flew her home to Thunder Bay for the Christmas holidays, but they refused to pay for her ticket back to Toronto. Knowing she could not afford to get back to her son, she said she reluctantly signed the adoption papers. Right after, Ms. Francis said the social worker revealed the child could have easily been transferred to Thunder Bay, where Ms. Francis said she had a friend who would have been willing to house her and her baby.

An Ontario woman named Suzanne, who asked to conceal her identity because her family does not know she put a child up for adoption in the 1980s, is also considering joining the suit.

Suzanne said she tried to revoke her consent within the 21-day period, but said she was stonewalled by her social worker, who refused to meet with her, and by the children’s aid society, which bounced her back to the social worker and ultimately said there was nothing they could do.

Valerie Andrews, the executive director of Origins Canada supporting people separated by adoption, said over the weekend two more women added their names to a list of mothers registering for a future federal inquiry. More than 100 have so far signed up, she said.

When asked whether the government would consider such a probe, a spokesperson for Justice Minister Rob Nicholson said adoption is a provincial matter.

Source: National Post

Coerced adoption: Salvation Army launches review of maternity homes that housed unwed mothers

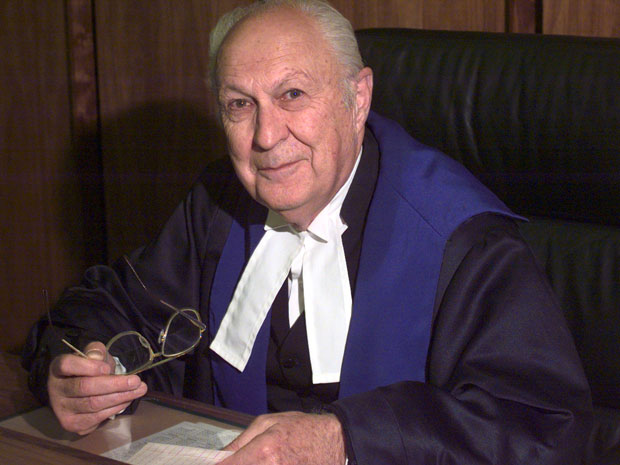

The Salvation Army says it is conducting an internal review into its historic maternity homes, just as a retired Calgary judge — who was once a high-ranking child welfare worker in the city — has come forward and corroborated some of the claims mothers have recently made about coercive adoption practices directed at unmarried mothers decades ago.

‘These people thought they were doing good – they thought these girls were sluts. They thought they were rescuing these children from a life of poverty,” said Herbert Allard, a former social worker, who said he was prompted to speak out upon reading the National Post’s story on forced adoptions over the weekend.

“At the time, I was divorced from the reality … It upset me in a way, but it’s just what went on.”

His account appears to confirm the coercion was systematic: He said the Salvation Army accepted teen mothers into their maternity homes on the condition they would surrender their baby, city social workers purposefully withheld information about revoking the adoption or the option of temporary wardship, and that unmarried mothers were punished in a Salvation Army hospital for getting pregnant out of wedlock.

“[Salvation Army] homes were operational during a time when there was a tremendous social stigma attached to being an unwed mother,” the church said in a statement responding to Mr. Allard’s account.

“The Salvation Army is currently conducting an internal review of the operation of these centres 40 to 50 years ago, including the treatment of our clients.”

The Alberta Ministry of Human Services, which includes Calgary and Area Child and Family Services, did not respond to a request for comment by deadline.

Mr. Allard’s public airing of what he called a “cultural conspiracy” comes ahead of an expected series of class-action lawsuits against provinces from Quebec westward, accusing the governments of kidnapping, fraud and coercion, according to Tony Merchant, the prominent lawyer heading the pending actions.

It also comes on the heels of a woman’s call for a public inquiry into adoption practices in Prince Edward Island, similar to an Australian probe that last month recommended the Australian government apologize to the “many parents whose children were forcibly removed” from their care.

The United Church said last week the matter here in Canada “will warrant a great deal of attention,” and spokesperson Bruce Gregersen promised the church was committed to working with mothers to uncover what happened in its maternity homes.

He has since spoken with Valerie Andrews, the executive director of Origins Canada supporting people separated by adoption, and said a researcher has been assigned to comb through the archives for documents such as board minutes and correspondence.

“Our role in this, among many things, is to help the story to be told,” Mr. Gregersen said Monday.

Mr. Allard was a social worker and assistant director of Calgary’s children’s aid during the late-1940s and 1950s, and said every surrender document signed by an unmarried mother would have crossed his desk. He also dealt closely with one of the city’s two female social workers who worked with pregnant unmarried mothers, and who often visited them in church-run maternity homes and at the Salvation Army’s Grace Hospital.

Beyond the claims already put forward by mothers now fighting for a federal inquiry into Canada’s historic adoption practices, Mr. Allard said the director of Calgary’s children’s aid had full discretion in deciding whether or not to honour a woman’s desire to revoke her surrender if she changed her mind within the cooling-off period.

“Mothers were sometimes successful, particularly if the baby wasn’t attractive — if the father was Ukrainian, for example,” said Mr. Allard, 85, adding that an English, white girl was considered a “premium” child.

Mr. Allard said surrender documents were sometimes sanitized so a child would appear more attractive to prospective parents on paper. If the document said a mother had a criminal background and said nothing about the father, a children’s aid social worker might lie and say the father was medical student — “that was the classic example,” he said.

‘The more adoptable the child was, the less likely it was she would get it back.’

He also said women often signed surrender documents while they were still recovering from labour.

“What really bothered me was that some of these women were still in post-delivery trauma,” Mr. Allard said. “[The surrenders] were done right away, sometimes because the mother just wanted to leave and get out of there.”

Mr. Allard said the social worker he dealt most closely with never told women of their right to revoke the adoption or to request a temporary wardship so they could find work and a place to live. In fact, he said she told the women their decision was permanent.

“She had great sympathy for the girls, but she was also part of the culture where unwed women did not keep their child,” he said. “She really struggled with the pain of this.”

He said the social worker sometimes came to his office crying because of the way the Salvation Army officers treated unmarried women in their Grace Hospital, where single women were segregated from married women, he said. In contrast to the accounts of women who said they were denied the chance to hold their baby, Mr. Allard said he knew of women who were forced to nurse their child, even after agreeing to an adoption.

“The idea was that if you made it easy for women to hatch and give the baby away, then that would be a bad idea,” Mr. Allard said. “The bonding would remind them of what a terrible thing they’d done … It was also a form of punishment, because it broke the woman’s heart when they gave them up.”

A social worker’s decision to conceal information about a woman’s options appears to have been more widespread than isolated.

Lori Chambers, who pored over thousands of archived children’s aid cases for her book, Misconceptions, about unmarried mothers in Ontario from 1921-1969, said social workers would not have wanted to encourage unmarried women to keep their baby.

In a 1970 letter to what was then called the Ontario Department of Social and Family Services, an adoption coordinator named Victoria Leach said many of the young girls she visited in a Presbyterian-run maternity home were ill-informed about adoption appeals and short-term wardships.

“I had things said to me yesterday like … ‘My social worker never mentioned that to me,” Ms. Leach wrote.

She suggested the department publish a brochure, “not unlike our ‘Adoption Procedure in Ontario’ booklet, which … would outline in detail some of the avenues open to them.” At the bottom of the typed letter, though, there is a handwritten note to the attention of the director, Betty C. Graham, that said, “If the branch prepared it, I’m sure there would be undue criticism of the contents.”

Karen Lynn, who was 19 when she was sent to Armagh in 1963, said no one ever asked her if she wanted to keep her unborn child.

“Nobody who was unwed kept their baby,” said Ms. Lynn, who said she was known only as Karen No. 1 at Armagh, as part of the matron’s bid to protect her family’s reputation. “I’ve only met a handful of women who said [adoption] was their free choice. Everyone else understands we had no choice.”

Mr. Allard, who was in 1999 celebrated by the University of Calgary as a community leader and awarded an honorary degree after 37 years of judicial service, was active in the United Church and in the 1960s helped close the church’s homes for “fallen women.” He said women there were sometimes punished by being placed alone in a “thinking room” with nothing but the Bible.

“I don’t think it could have gone a different way, simply because of the culture at the time,” said Mr. Allard, who has since been outspoken about the need for open adoptions so children can trace their roots. “There were caring people out there, but the times inhibited them.”

Source: National Post

‘The fathers had no say’: Men tell another side of coerced adoption story

As more mothers come forward to push for an inquiry into Canada’s historic adoption practices targeting unmarried women, fathers have emerged to say they, too, were coerced into surrendering their children.

In Sutton, Ont., Raymond Cave said he was never asked to sign a surrender document in 1967, even though the people handling the adoption knew he was the father. In Saskatchewan, Bernard Shepherd said he was only allowed to look at his baby before signing the surrender document, and said he was never told about the option for a temporary wardship so he could take some time to consider raising the child with his mother’s help. And an adoptee remembered how when she contacted her natural father, he had no idea she existed.

“There’s a whole other side to this story,” said Mr. Cave, whose high school sweetheart, Linda Dawe, got pregnant at age 17 in 1966, when the couple was teenaged and too young to legally marry. “The fathers had no say — no legal rights. No one was ever supposed to know who the father was, let alone come ask me for a signature. It was like I didn’t exist.”

The Salvation Army said on Monday it is conducting an internal investigation into its maternity homes after the National Post reported the stories of several women who say they were coerced into giving up their babies decades ago because they were not married.

Since then, an adoption-oriented Facebook group has been flooded with comments from mothers. “Honestly I never thought I’d see this day,” a woman named Lori wrote on the Facebook page for Origins Canada, which is pressing for a federal probe into this country’s adoption practices. “Validation is an amazing healer,” wrote Sharon Pedersen.

But Mr. Cave is telling the fathers’ side of the story, just as more and more mothers register with Origins Canada for any future federal inquiry. Governments across Canada are also expected to soon be hit with a series of provincial class-action suits, accusing them of kidnapping, fraud and coercion, according to Tony Merchant, the prominent lawyer heading the pending actions.

Although Mr. Cave and Ms. Dawe lost touch soon after they surrendered their daughter, Karen, in 1967, they reunited in 2006 at their Sir James Dunn high school reunion in Sault Ste. Marie. Now married and reunited with their child, the couple are sharing their story.

They fell in love in Grade 10, but when Ms. Dawe became pregnant, her religious parents sent her to the Salvation Army’s Bethany maternity home in Toronto, where she was told she had no choice but to give her up her unborn child, she said. Mr. Cave said the home permitted only family to visit Ms. Dawe.

When Ms. Dawe was eight months pregnant, Mr. Cave saved up some money and took the train to arrange a secret meeting. Ms. Dawe got a pass to leave the home for a few hours, and the couple met at the King Edward Hotel, where they said they struggled to scheme a plan to keep the child. They had sex, too, and laughed because “she couldn’t get any more pregnant,” Mr. Cave joked.

One month later, Ms. Dawe gave birth at the Salvation Army’s Grace Hospital, where she said she was not given any painkillers, despite needing 100 stitches after labour. She said she does not recall signing a surrender document then, but she did not leave the hospital with her baby in her possession.

A month later in a Sault Ste. Marie courtroom, Ms. Dawe officially surrendered her child. When she asked to put Mr. Cave’s name on the surrender papers, she said the court clerk told her it was no use. His name would be whited-out.

The couple said they were never told of their right to revoke consent if they changed their mind during a cooling-off period, nor of the option for a temporary wardship, which might have bought the couple time since Ms. Dawe had turned 18 and could legally marry.

Herbert Allard, a retired Calgary judge who was a high-ranking child welfare worker in the early-1940s and 1950s, said fathers were treated as “non-persons.” They sometimes signed surrender documents under the threat that children’s aid would come after them for exorbitant amounts of child support, one historian has said.

“We didn’t think they had rights at all,” Mr. Allard said, adding that some men took advantage of the cultural norms and left the woman to deal with the child alone. “If some men did want to keep the baby, it didn’t matter. They had no status.”

Mr. Merchant said since the National Post’s report on Saturday, about a dozen more people have come forward to join prospective class-action suits. Mr. Shepherd, for his part, said he is considering joining any future suit in Saskatchewan and hopes he will someday connect with his son, who will be 31-years-old on Nov. 4.

“I think if I’d had just a little time, if I’d been given some options, I at least could have talked to my family about it,” said Mr. Shepherd, who was 21-years-old when he got his then 19-year-old girlfriend pregnant in 1981. “That’s what was so disappointing.”

Mr. Merchant said he now has prospective plaintiffs in all provinces Quebec westward, as well as in Newfoundland & Labrador and New Brunswick.

“When a child is taken,” he said, “that cuts the father off from the child just as much as it cuts the mother off.”

Source: National Post

‘These women didn’t know their options’: Ontario urged to consider inquiry into coerced adoptions

Ontario’s NDP urged the Dalton McGuinty government Wednesday to look at launching an inquiry into the province’s historic adoption practices in the wake of accusations from women who say they were coerced by social agencies, medical workers and churches into giving up their children.

“I would urge the Minister of Children and Youth Services in Ontario to give serious consideration to calls for an inquiry, and to listen carefully to the views of groups representing those who have been affected by these practices in maternity homes and elsewhere,” Monique Taylor, the Ontario NDP’s critic for children and youth services, said in a statement.

The ministry said in an email earlier this week the Ontario government “does not have plans” for an inquiry.

Ms. Taylor’s call comes after the Salvation Army and the United Church both announced reviews of their maternity homes’ practices from the 1940s to the 1980s, when abortion was either illegal or difficult to access, birth control was not easily accessible and unmarried mothers were viewed by authorities as too feeble-minded to parent.

Also on Wednesday, two former social workers stepped forward to confirm that they had been part of agencies that had pressured unwed mothers into handing over their babies for adoption. One apologized for his role in a system he said was “stacked” against unmarried mothers.

“It was a travesty of justice,” said Sam Sussman, a former children’s aid worker in Winnipeg and now an assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Western Ontario. “I regret being part of the system. I bought into the philosophy of my peers and the people I looked up to…. I apologize.”

Mr. Sussman, who arranged for unmarried teens to stay at church-run maternity homes during their pregnancies — a clear path to adoption, he acknowledged — said he is considering formally asking the Manitoba government to launch an inquiry.

Despite obtaining a masters degree of social work degree from the University of Manitoba in 1965, Mr. Sussman said he was unaware at the time of a woman’s right to revoke her consent for putting her child up for adoption if she changed her mind, nor of the option for putting her baby into temporary wardship if she wanted to buy time and find work or a place to live.

“These women didn’t know their options, so if that’s coercion, then yes, they were coerced,” Mr. Sussman said.

Baldwin Reichwein, a social worker and former acting director of what was once the Alberta Public Welfare Department, said he would support a provincial inquiry in Alberta partly because he questions the validity of some women’s adoption agreements.

Mr. Reichwein, who dealt with unmarried mothers in a community just south of Edmonton during the 1960s, said he was particularly concerned that some women signed surrender documents while they were in a vulnerable or disoriented state. In Alberta at the time, he said consent was valid so long as it was signed no sooner than five days after birth — a time when a woman could still be recovering from labour, confused, or still under medical care.

“I’m not a psychologist, but what the hell is five days?” he said, adding that back then women were often in the hospital for about a week. “You can say, ‘She signed the consent form,’ but in hindsight, given the circumstances, I have some doubts about whether those consents would stand up.”

Lori Tkach Blatz said she was heavily medicated the day she signed a surrender document in 1988 in Alberta, and that the person handling the paperwork told her to count backwards from 10 as a test of her lucidity. Ms. Tkach Blatz said she failed, but she said the woman told her it was “close enough.”

The National Post first reported on Saturday on a series of class-action lawsuits planned against several provinces that will accuse the governments of complicity in the kidnapping of babies, fraud and coercion, according to Tony Merchant, the prominent Saskatchewan attorney heading up the pending actions.

Mr. Reichwein and Mr. Sussman add their voices to that of retired Calgary judge and former social worker, Herbert Allard, who on Monday corroborated some of the claims mothers have made about systemic and coercive adoption. Mr. Allard said the Salvation Army accepted teen mothers into their maternity homes on the condition they would surrender their baby; that social workers purposefully withheld information about the mother’s options for revoking the adoption or the option of temporary wardship; and that unmarried mothers were emotionally punished in a Salvation Army hospital for getting pregnant out of wedlock.

“The mothers know their truth, but one thing we have been seeking is acknowledgment and validation,” said Valerie Andrews, who heads Origins Canada, a group supporting people separated by adoption. “This helps.”

Today a social historian, Mr. Reichwein said he has copies of various historic reports proving the Alberta government had an agenda when it came to unmarried pregnant women decades ago. In response to an explosive 1947 report by the Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire alleging coerced adoptions, Mr. Reichwein said three judges responded with a Royal Commission report to the Alberta Department of Public Welfare. In their report, he said they stated that an unmarried woman’s punishment should be “immediate and grievous” and that “the state ought to do whatever it can to remove the damage of illegitimate birth from the child.”

‘Surrender has been in the closet for too long, but it’s slowly starting to come out’

“Surrender has been in the closet for too long, but it’s slowly starting to come out,” Mr. Reichwein said. “Social workers say they did the right thing, but did they? Did I? It’s hard, but we have a moral duty to look back.”

Cathy Ducharme, a spokeswoman for Alberta’s Human Services, said earlier this week the ministry is “looking into the situation.” She did not respond to a follow-up request for comment on Wednesday.

Source: National Post

‘You suffered just as much’: Adoptees gain new insight into parents’ choices as coerced adoption stories come to light

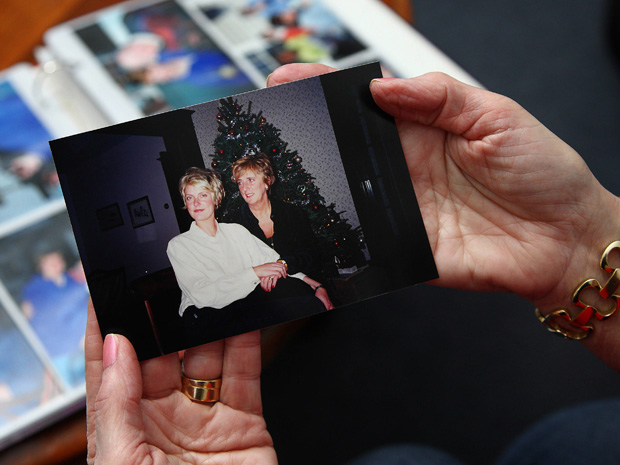

On this day, 48 years ago, Betty Meredith says she was tied down to a birthing table, covered with a sheet so she could not see her daughter being born and then unknowingly given drugs to dry up her breast milk. Teenaged and unmarried at the time, she ultimately surrendered her child for adoption, and Friday her daughter, Betsy Eldon is celebrating her birthday.

The pair reunited 15 years ago and have grown close, but with the public airing of Canada’s historic adoption practices, Ms. Meredith said her daughter finally understands the magnitude of the coercion she said she experienced — both at the Salvation Army maternity home, where she was known only as Betty to protect her family’s reputation, and at the Ottawa Grace Hospital, where she said she was given no food, no water and no kindness, all because she was unmarried.

Since a National Post investigation began uncovering stories about coerced adoption among unmarried women from the 1940s to the 1980s, several adoptees have contacted the newspaper saying the reports have validated their mothers’ accounts and helped prove that the choice to surrender was not fully hers. Some women had told their stories on the record for the first time, and they said their children have since expressed shock and compassion.

One man reached out on Facebook to the brother he never met — a stranger, all because people in the 1960s “thought they knew better than” his mother, he said — and they are making plans to meet face-to-face.

‘But the stuff about being tied down? When I read that, I was horrified’

“I had already explained and explained and explained over the past 15 years, but when you see it in the newspaper, and you see it coming from so many other mothers, it validates it in a different way,” said Ms. Meredith, who had been interviewed for one of the articles earlier this week. “[Betsy] said she suddenly realized what these mothers endured and said, ‘You suffered just as much as I did, but in a different way.’ Coming from Bets, that was kind of mind-blowing.”

“I knew my mom was in a maternity home, and that she wasn’t allowed to use her last name,” Ms. Eldon said. “But the stuff about being tied down? When I read that, I was horrified … Our relationship is changing and evolving all the time, but this has given me a new perspective.”

The Ontario NDP on Wednesday urged the Ontario government to consider a provincial inquiry into the claims put forward by Ms. Meredith and several others, and three social workers in Alberta and Manitoba this week confirmed that social workers and churches targeted unmarried women and pressured them into giving up their babies.

In Saskatchewan, Jani Francis said she received a long letter this week — not from the son she surrendered to adoption, but from another son, Paul Saxberg, lamenting what she went through and assuring her he now understands why she battled chronic depression much of her life.

“That letter meant the world to me,” said Ms. Francis, who had earlier told the National Post she was coerced by a social worker into handing over her son, David, in Toronto in 1969. “To be able to talk about it takes the shame away. It puts it all on the table. It’s very healing.”

Mr. Saxberg said he wishes the public acknowledgement would have happened decades ago because perhaps he could have had a better relationship with his mother growing up. He said he was inadvertently cruel to her — their tense relationship meant he never asked questions about the adoption, and he never knew what she experienced as a teenager in the 1960s.

Ms. Francis said the nurses at the Toronto Grace Hospital only sometimes relented when she begged to see her baby, and she said a social worker withheld information about the option for a temporary wardship in Thunder Bay, Ont., where her family lived, until the moment after she signed the surrender.

“My initial reaction, to be honest, was one of rage,” Mr. Saxberg said. “I’m angry that people cheated me out of four decades of having an older brother because they thought they knew better than my mother. On the other hand, there’s a silver lining. It’s wonderful to have some insight into what my mother went through. I feel like I understand her more — like I relate to her more.”

Mr. Saxberg said he has never met his brother, who was reunited with their mother in 2004, but said over the past few days they have connected on Facebook and plan to meet.

“It’s already changing my relationship with David,” he said from his home in Calgary. “I’ve realized exactly what I’ve lost. I have wonderful brothers and sisters, but I could have had him, too.”

Ms. Meredith said her entire family has been affected by the adoption and her reunion with Ms. Eldon, and said she sent her son, Rick, a link to one of the stories on Facebook in the hopes he would better understand what happened after her parents sent her miles away to the maternity home in Ottawa nearly 50 years ago.

“He called me and said, ‘Wow, I had no idea that’s what you had been through,’” Ms. Meredith said. “Not only does Betsy now understand that I went through a lot of angst, but so does my youngest son. Adoption affects a lot of people, and this discussion of it is extremely important.”

Source: National Post

B.C. government hit with class-action lawsuit over coerced adoption claims

The British Columbia government was on Friday hit with a class-action lawsuit accusing the province of abduction, fraud, and coercion in connection with adoptions among unmarried women from the 1940s until the early 1990s.

The lead plaintiff is today a fourth-year psychology student named Cassandra Armishaw, who became pregnant at age 17 in 1985 after being sexually assaulted in Penticton, B.C, according to the statement of claim. When she was in labour at Vancouver’s Grace Hospital, she alleges a social worker entered the room and said “when you’re done here I’m taking that baby,” the claim says.

“She was still delivering the baby, and tried not to push,” it says.

Ms. Armishaw alleges she was not immediately allowed to see, hold, or touch her baby girl.

The lawsuit is the first in an expected series of similar class-actions planned against all the provinces Quebec westward, as well as in New Brunswick and Newfoundland and Labrador. Tony Merchant, the prominent Saskatchewan lawyer heading the actions, said he expects to file in Ontario and Quebec next week.

A spokesperson for the B.C. Ministry of Children and Family Development said it would be inappropriate to comment now that a suit has been filed.

Earlier this week, Brian Cotton said the government is “not aware of any official policy that would have forced unwed mothers to give up their children for adoption in British Columbia.”

None of the claims have been proven in court.

Since the National Post launched an investigation into coerced adoptions last weekend, dozens of mothers have emerged to say they were coerced or forced by social workers, medical staff, and churches into giving their child up for adoption because they were unmarried. Three former social workers, two in Alberta and one who worked in Manitoba, have come forward to corroborate some of the claims put forward by the mothers.

The Salvation Army and the United Church have said they are reviewing their maternity homes’ practices, and the Ontario NDP has urged the Dalton McGuinty government to “give serious consideration” to calls for a provincial inquiry.

Among the mothers who have told their stories to the National Post, several said they experienced coercion in British Columbia.

Sharon Pedersen said she was 20-years-old in 1964 when she was drugged and tied to her bed during labour and then shown four different babies through the nursery window at a hospital in Victoria. She ultimately signed adoption papers at the local children’s aid society, she said, but not before social workers held a pen in her hand and threatened to call the police because she was screaming and throwing furniture in protest.

Hanne Andersen said her B.C. hospital records say “Baby for Adoption” even though the teenage single mother had planned to keep the baby. Ms. Andersen, who became pregnant at age 15 in 1982, said nurses allowed her to hold her child just once.

Ms. Armishaw could not be reached on Friday, but her statement of claim says she feared another sexual assault in Penticton and moved to Vancouver. There, she claims she contacted social services to see whether she could receive assistance, but she alleges she was told no assistance was available. The claim also says a social worker testified in court that Ms. Armishaw was not able to care for herself — that Cassandra “did not eat nutritious food” and “thought other people were possessed by spirits — and that the baby should be put up for adoption.

The claim, filed to the B.C. Supreme Court on Friday morning, lists the “Province of British Columbia, as represented by the Attorney General” as the sole defendant. “The Defendant took away the right of the Class Members to make a free choice about whether to adopt their children,” it says.

The class captures unmarried women whose babies were “taken immediately following delivery and then placed for adoption,” according to the claim, which seeks general and special damages for the lost opportunity to parent, medical treatment without consent, and mental distress.

It says unmarried mothers were excluded from the regular maternity wards, and that adoption consents were executed immediately following birth, in contravention of the ten-day waiting period before a surrender can be executed.

“I don’t think there is any question there was a policy where, if a child was born outside of a marriage, that child was not to remain with the mother,” said Mr. Merchant, whose firm secured a $2-billion settlement in the 2006 Indian Residential School class action.

Mr. Merchant, who said upward of 200 women have so far signaled interest in class-actions across the country, said the suits will attempt to saddle the provinces with responsibility for the wrongdoings of church-run organizations because they were provincially funded agents. He said he hopes the case will be certified by a judge within six months, allowing the case to proceed.

Source: National Post

The Australian precedent: Women fighting for an adoption inquiry look across the ocean

For the first time in 50 years, Barbara Maison does not feel “so completely alone” in her grief over being coerced to surrender her son for adoption, and after four decades of shame, Robin Turner only now feels validated and worthy of respect.

Both women recently testified before an Australian Senate committee probing the country’s adoption practices from the 1940s to the 1980s, and both were featured in an explosive report released last month urging the Australian government to apologize to the thousands of women who were coerced by social workers, medical staff and churches into handing over their babies, simply because they were unmarried.

Hundreds of mothers like Ms. Maison and Ms. Turner gave submissions to the Senate committee, and while several lamented how difficult it was to put their accounts on the public record, most said the process was healing — that it has helped them put to bed some of the guilt they felt for surrendering their children all those years ago, and helped them mend relationships with their families because they no longer feel so ashamed.

The path to what Ms. Maison called a “cathartic” moment was not a clear one. Australian mothers had been fighting for a federal inquiry for more than 15 years — at least since Lily Arthur and Diane Wellfare co-founded Origins Australia, an organization supporting people separated by adoption, in 1995.

The pair dug through archives for evidence, launched letter-writing campaigns and met with politicians. They fought tirelessly to persuade the government to acknowledge the suffering of mothers who say the coercion was systemic: From the social workers who never told them about their right to revoke a surrender and who secured their signatures while they were still on powerful medication in the hospital, to the doctors and nurses who tied them to the birthing table and then did not let them see or touch their babies, to the church-run maternity homes, where women were essentially groomed for adoption.

“Diane died doing this work,” said Valerie Andrews, the executive director of Origins Canada, which was founded in 2002 and which she took over in 2007. “She and Lily pressed, and continually pressed, until they finally got an inquiry.”

Ms. Andrews is spearheading the push for a probe in Canada, and looks to the Australian experience for guidance. There, momentum built at the state and church level, until finally the federal government undertook its own inquiry. In 1999 and 2000 respectively, the Tasmanian and New South Wales parliaments conducted inquiries, and in 2010 the government of West Australia outright apologized.

Just last year, Catholic Health Australia, the country’s largest non-government health-care service, apologized, calling the era of forced adoptions a “shameful and regretful time.” In its submission to the inquiry, it admitted that about 150,000 Australian unwed mothers had their babies taken against their will between the 1950s and 1970s, according to an Origins Australia newsletter.

Ms. Arthur said the Senate was ultimately “forced” into launching an inquiry, given the combined pressure of the state inquiries, the growing awareness of the damage done to the women’s mental health, and the surging activism among mothers galvanized by the apologies.

One Australian senator also said social media such as Twitter and Facebook were key in lobbying the support of federal politicians.

“Canadians have the same need to have their story on the record, and to also receive support and acknowledgment,” Ms. Arthur said in an email.

Ms. Andrews estimates upward of 350,000 unmarried Canadian mothers were persuaded, coerced or forced into adoption, basing her calculation on Statistics Canada data on illegitimate births from 1945 to 1973 and the rough rate of adoption among unmarried women at the time.

As with Australia, the quest for a Canadian inquiry is not likely to culminate overnight: So far, Justice Minister Rob Nicholson has said only that adoption is a provincial matter, and Ms. Andrews has yet to find a politician who will champion the cause either in the Senate or the House of Commons.

But ever since the National Post on Saturday launched an investigation into coerced adoptions in Canada, Ms. Andrews said the momentum has been growing. Over the past few days, she said she has secured face-to-face meetings with the Salvation Army and the United Church — both of which launched reviews of their maternity homes’ practices this week — and her federal MP, Costas Menegakis. She also recently received a call from Ontario’s Child Welfare Secretariat and will be meeting with its director next month.

While the Australian movement swelled from the state level to the federal level, Ms. Andrews said Canada now has the “Australian experience to stand on,” and said she hopes to bypass the provincial level and go straight to a federal inquiry.

Calling the recent reports in the National Post “extremely troubling,” Irwin Cotler, the Liberal Justice Critic, said he “has hope that these women will have a chance to tell their stories and that some sort of truth and reconciliation will be reached for all those affected by this unthinkable practice.”

Still, he echoed Mr. Nicholson’s office and said any inquiry would likely need to be initiated by the provinces.

Adoption does not fall under federal jurisdiction in Australia either, and yet Senator Rachel Siewert, chair of the Community Affairs Committee, tabled a motion urging her government to probe the country’s historic adoption practices. Senator Claire Moore, who also sits on the committee, said Parliament had a “role to respond to issues that had such an impact on people across the country.”

Ms. Siewert outright recommended that the Canadian government undertake a federal inquiry: “I think the mothers, fathers, adoptees and families affected would get a lot out of it. Their pain, hurt and trauma needs to be acknowledged and addressed.”

And the Australian Association of Social Workers — which admitted to the committee that “many women were not given the necessary assistance, and in some cases were deliberately denied access to counselling services prior to giving consent and were not informed of their legal rights” — urged the Canadian Association of Social Workers to co-operate fully with any future federal inquiry here.

The National Post contacted several members of the House of Commons Human Resources Committee, as well as the Senate’s Social Affairs Committee and the Legal and Constitutional Affairs committee, to see whether they would consider tabling a motion for an inquiry. Two said they were not available for comment, one declined an interview, and one said her committee would not be the one to pursue such a matter.

Despite all this, Baldwin Reichwein, one of three former social workers who this week came forward to corroborate some of the claims put forward by the mothers, said he has “felt some pin pricks” and believes momentum is growing toward a full-blown public airing.

“These things have a habit of needing a lot of time for people to be willing and brave enough to speak out,” he said. “I think there’s merit for [this history] to come out … It’s time.”

Source: National Post

NDP MPP Monique Taylor ‘shocked’ at lack of response to push for coerced adoption probe

The Ontario NDP on Monday urged the Liberal government during Question Period to order an investigation into the province’s past adoption practices, citing recent accusations from women who say they were coerced by social agencies, medical workers and churches into giving up their children because they were not married.

“Unmarried mothers were forced to give up their newborn children,” Monique Taylor, the NDP’s children and youth services critic, said at Queen’s Park this morning. “Will the Minister meet with these mothers and hear their stories, and help them uncover what happened to Ontario women in maternity homes?”

Eric Hoskins, the Minister of Children and Youth Services, said he has been following the recent media investigation into Canada’s historic adoption practices “very, very closely” and said “as a parent myself, these stories are extremely difficult to read.”

When Ms. Taylor pressed him about launching an inquiry, Mr. Hoskins said his ministry is “not aware of a concerted policy to obtain babies for adoption from unmarried mothers” and then cited the province’s current adoption laws and oversights.

Monday’s exchange comes ahead of a pending class-action lawsuit, which is expected to be launched this week against the Ontario government and will accuse the province of abduction, fraud, and coercion in connection with adoptions among unmarried women from the 1940s until the early 1990s, according to Tony Merchant, the prominent Saskatchewan lawyer heading a series of actions across the country.

In an interview following Question Period, Ms. Taylor said she was “shocked” at Mr. Hoskins response, and said she plans to meet with him to discuss what she called a “huge issue” sometime in the next day or so.

“Is he planning on just brushing it under the carpet, like this doesn’t exist?” asked Ms. Taylor, who said she has received calls from several women saying they were coerced into giving up their babies. “It’s the government’s duty to [investigate] … These women don’t want to live with their dirty little secret anymore. They want to be acknowledged.”

Since the National Post launched an investigation into coerced adoptions earlier this month, dozens of mothers have emerged to say they were coerced or forced into surrendering their children between the 1940s and 1980s, a period when abortion was either illegal or difficult to access, birth control was not easily accessible and unmarried mothers were viewed by authorities as too feeble-minded to parent.

Several of these mothers recounted their experiences in Ontario.

Karen Lynn said she was 19 when her mother sent her to a home for unmarried pregnant women in Clarkson, Ont., in 1963. There, she was known as Karen No. 1 to protect her family’s reputation, and said it was clear she would not have been allowed to stay there if she did not agree to an adoption.

Teenaged and unmarried, Valerie Andrews said she was unknowingly given medication to dry up her breast-milk. Social workers in Sudbury, Ont., never told Esther Tardif she was eligible for social assistance and said if she loved her unborn child, she would let him go.

Former NDP MPP Marilyn Churley, who became pregnant at age 18 in 1968, said the prevailing attitude of the day was to punish the women — “by taking the baby, she would learn a lesson,” she told the National Post earlier this month. She said her social worker never talked about alternatives to adoption and that she endured a “horrific” 24-hour labour without painkillers.

“After I gave birth, they started to take my baby out of the room and I jumped off the table and started to chase the nurse,” said Ms. Churley, who said she was threatened with restraints. “I was screaming at them, ‘I need to see my baby.’ They brought him close to me, and I could reach out and touch his face and head. I never held him. They told me ‘no.’ And then they took him away.”

Ms. Churley, who became a leading advocate for open adoption records in the province, said she signed a surrender document within a day of giving birth to the child she briefly named Andrew Fitzpatrick — while she was still in the hospital recovering from labour.

“I don’t feel like I had a choice, but I don’t feel like I was coerced by any single individual,” she said, adding that she has since reunited with her son, Bill.

Upon reading these accounts, Ms. Taylor released a statement last week calling on the Dalton McGuinty government to look at launching an inquiry. At the time, the Children and Youth Services Ministry said the government “does not have plans” for a probe. On Monday, a spokesperson said the government’s position had not changed.

Still, Ms. Andrews, who today heads Origins Canada supporting people separated by adoption, said she is slated to meet in April with the director of the province’s Child Welfare Secretariat, which she said reached out to her last week. The ministry said in a statement that “officials will listen to her concerns.”

The Salvation Army and the United Church have so far announced reviews of their maternity homes’ practices, where unmarried mothers sometimes lived during their pregnancy.

Over the past week, three former social workers have also come forward to corroborate some of the claims put forward by mothers, including that social workers purposefully withheld information about revoking the adoption or the option of temporary wardship.

If you have information on coerced adoptions in Canada, please contact Kathryn Blaze Carlson at kcarlson@nationalpost.com.

Source: National Post

Senator joins growing call for probe into forced adoptions

Amid growing evidence of coercive adoption practices targeting unmarried mothers between the 1940s and 1980s, politicians across the country are calling for investigations into what many mothers allege was a systemic bid to secure their babies for adoption.

Since the National Post’s March 10 report detailing the accounts of seven women, dozens of mothers have contacted the newspaper saying they were coerced by social workers, medical practitioners and churches into surrendering their children.

Senator Art Eggleton, deputy chair of the Senate social affairs committee, said Canada’s historic adoption practices “should be investigated” and said if the federal government were to launch a public probe, it should be handled by a judicial inquiry or a special committee struck specifically to uncover what happened all those years ago.

“What happened to these women is a tragedy,” the former Liberal cabinet minister said in an email. “The fact it was a different time with different attitudes from today doesn’t make it any easier on those who endure.”

Irwin Cotler, a Liberal MP and the party’s justice critic, said he welcomed the Salvation Army’s announcement last week that it is conducting an internal investigation into its maternity homes’ practices, and said in a statement he hopes “other similarly implicated groups undertake similar measures.”

Vancouver MP Libby Davies, the deputy NDP leader, on Tuesday urged the Conservative government to launch a federal inquiry and said Justice Minister Rob Nicholson and Health Minister Leona Aglukkaq should “take leadership and acknowledge what happened to women all across the country.”

“This is a national issue,” she said from her constituency office, where she last year met with Hanne Andersen, a mother who says her daughter was “stolen” by medical staff shortly after she gave birth. “When I first heard about this, I was shocked. This really happened? So systemic? Who knows how many women were affected.”

Ms. Davies has twice written to Mr. Nicholson asking him to consider a federal inquiry, and said she has not yet received a response. She said she plans to raise the issue with NDP MPs who sit on relevant House of Commons committees in the hopes that one of her colleagues might table a motion calling for a national probe.

Julie Di Mambro, a spokesperson for Mr. Nicholson, said last week adoption is a provincial matter, and both Mr. Eggleton and Mr. Cotler suggested it would be more appropriate for the provinces to address the issue. When pressed again on Tuesday given recent allegations of Criminal Code violations, Ms. Di Mambro reiterated the government’s position.

‘The fact it was a different time with different attitudes from today doesn’t make it any easier on those who endure’

Adoption does not fall under federal jurisdiction in Australia either, and yet an Australian Senate committee launched an inquiry that last month culminated in a report urging the government to apologize. Senator Claire Moore, who sits on the Australian committee that headed the probe, said her Parliament had a “role to respond to issues that had such an impact on people across the country.” Senator Rachel Siewert has outright recommended that the Canadian government undertake a federal inquiry here, too.

Provincial politicians are likewise calling for investigations into claims that social workers never told unmarried women about their right to revoke an adoption or the option of a temporary wardship, that women were tied down to the birthing table and never allowed to see or hold their baby, and that unmarried mothers were specifically targeted for their healthy, white babies.

On Monday, the Ontario NDP pressed the Liberal government to take action, asking the Minister of Children and Youth Services during Question Period to consider launching a provincial inquiry.

Minister Eric Hoskins said he had been following the recent media investigation “very, very closely” and said “as a parent myself, these stories are extremely difficult to read.” He said his ministry is “not aware of a concerted policy to obtain babies for adoption from unmarried mothers.”

One provincial politician in B.C. had already written to the federal justice minister asking him to “uncover what really happened,” according to an April 5, 2011, letter written by MLA Shane Simpson and obtained by the National Post.

Ms. Andersen — a Vancouver woman who says her hospital records were marked with the words “Baby for adoption” even though she never planned on surrendering her child when was she was 16 in 1983 — said she hopes any future federal inquiry will compel hospitals and children’s aid societies to release records she said have sometimes been difficult, if not impossible, to acquire.

Calling accounts put forward by women such as Ms. Andersen “extremely troubling,” Mr. Cotler said he has “hope that these women will have a chance to tell their stories and that some sort of truth and reconciliation may be reached for all those affected by this unthinkable practice.”

Source: National Post

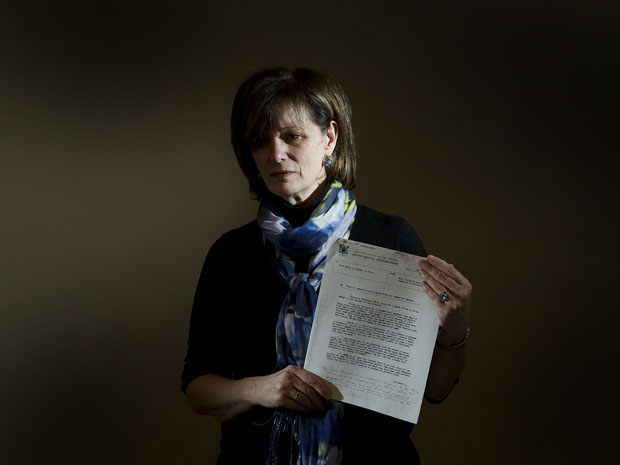

Your baby is dead: Mothers say their supposedly stillborn babies were stolen from them

This is how the woman, then young, remembered the August day in 1963 on which she gave birth to her illegitimate daughter: She was in an Edmonton hospital; the doctor ordered she receive an injection. She blacked out, and when she started to come to, a male voice said: “knock her out.”

She claimed she woke up sometime later and was told she had given birth to a girl, but the baby had died.

Her baby girl did not die, though. She was adopted by a married couple.

“I never wanted to give up any child of mine for adoption,” the Edmonton mother swore in an affidavit before her recent death. “I went through my entire life believing that the baby I carried in 1963 had died…. I believe that I was lied to and my baby was stolen from me.”

Since the National Post launched an investigation earlier this month into coerced adoptions between the 1940s and 1980s, dozens of mothers have said they were forced by social workers, medical staff and churches into surrendering their child because they were young and unmarried.

But some of these women say they never surrendered their child at all: They say they were told their child was stillborn or died shortly after birth, when in reality they allege their baby was adopted or essentially handed to a married couple.

“In those days, it was just said the child was dead because that way the mother wouldn’t look for it,” said Lise Pageau, a regional director at Mouvement Retrouvailles supporting adoptees and natural parents, adding that she has personally spoken with at least a half-dozen mothers who allege this happened to them. “[Nurses and doctors] would show the mother a very, very, very sick baby and say the child would not pull through the night. Sometimes the child was already promised to a couple.”

The Edmonton mother’s daughter, who cannot be identified because of a publication ban, is suing the woman who raised her and the hospital where she was born, alleging that her adoptive mother and a doctor wrongfully arranged for her adoption some 40 years ago.

The daughter found her natural mother in 2004, but her mother thought she was “crazy,” court documents say. A DNA test later confirmed they were kin.

It is difficult to know for certain how often Canadian women were lied to about their baby dying. Unless a woman was contacted by her child later in life, she would not know that her allegedly dead child was actually alive.

Still, the accounts of mothers, such as the one who swore the affidavit, suggest the possibility that at least some babies born to single women were immediately or eventually transferred to married couples. In her 2011 book, The Traffic in Babies: Cross Border Adoption and Baby-Selling Between the United States and Canada, 1930-1972, McMaster University professor Karen Balcom wrote that in Nova Scotia there were “numerous examples of birth mothers who were falsely told that their children were dead so they would not interfere in adoption placements.”

Gary Whitbourn said his mother was 17 years old and unmarried when she gave birth to him in London, Ont., on Oct. 8, 1975. She named him Jason Albert, but hours later she was told he died, Mr. Whitbourn said.

“Part of me was skeptical — maybe she just didn’t want to admit the guilt of giving up a baby and would rather blame it on someone else, but I’ve come to realize that can’t be true,” said Mr. Whitbourn, who met his natural mother in 1997. “It’s unnerving. You assume these things don’t happen in Canada.”

A Canadian named Tina Kelly filed a UN report a decade ago alleging that, as an unmarried woman in 1970, she was falsely told her baby died overnight because of heart trouble. She claims she was not allowed to see her son, whose adoption she alleges was arranged by a doctor who took a bribe.

The Australian Parliament says the so-called dead baby scam happened there, and a nun in Spain was charged last weekend with allegedly committing this very crime over the course of the 1950s to the 1980s. During those decades in Canada, abortion was illegal or difficult to access, birth control was not readily available and unmarried mothers were seen as loose women too feeble-minded to parent.

An Australian Senate committee investigating that country’s historic adoption practices recently reported that especially swift transfers had a formal title, rapid adoption.

“This generally referred to the process whereby a married woman whose child had been stillborn was offered a child for adoption in its place,” says the committee’s explosive February report, which urged the government to apologize for forced adoptions.

One Australian woman named Valerie Linlow testified she was heavily drugged during labour and that medical staff told her she gave birth to a stillborn. Three decades later, she said a man knocked on her door saying he was her son.

Here in Canada, Ms. Kelly claims a doctor told her he would work with the Catholic Children’s Aid Society of Toronto to arrange for her baby’s baptism and burial. She alleges she was heavily drugged when a social worker from the society asked her to sign a document, which she says she thought was the paperwork for his baptism.

The 2003 UN report says she later requested a death certificate from the Toronto hospital where she gave birth, only to be told the records say her son was born healthy and went home with her. The Catholic society said its records show Ms. Kelly was a client in 1970, and that her son was made a Crown ward and ultimately placed for adoption.

“Ms. Kelly’s version of events reflected in the UN report bear no resemblance to the information in our records,” executive director Mary McConville said in a statement.

Ms. McConville also confirmed that in 2001 Ms. Kelly filed a lawsuit against the society, two physicians and the Toronto hospital. She indicated the suit was dismissed “on the consent of all parties.” Ms. Kelly declined an interview request.

Other women, such as the Edmonton mother, say they are positive they did not sign an adoption paper. The lawyer in that case, Robert Lee, said his client alleges her mother’s signature was forged.

“Most people would think my client is crazy for thinking she was stolen from her mom at the hospital,” said Mr. Lee, whose client declined an interview request for fear of legal repercussions. “It seems as if people thought they were acting in the best interests of the child or the mother, and out of their beliefs, they went on violating the rights of these families.”

The defendants deny any wrongdoing, and none of the allegations have been proven in court.

Sharon Pedersen, a B.C. woman who was unmarried and 20 years old when she gave birth in 1964, said she was not told her baby was stillborn, but said a social worker at the local children’s aid society nonetheless demanded she sign a death certificate, saying “Dear, this is just to help you realize this baby is gone.” Ms. Pedersen said she ultimately signed adoption papers, but not before social workers held a pen in her hand and threatened to call the police because she was screaming and throwing furniture in protest.

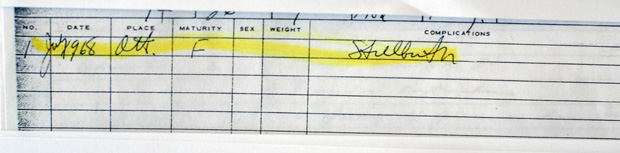

Sheri Sexton said her mother was not told she was stillborn, either, and instead signed surrender papers after hours of coercion at the hospital in July 1968. Still, Ms. Sexton said she is listed as a prior stillborn child on hospital records a year later when her mother gave birth to a girl, who was apparently born dead. Ms. Sexton suspects her sister is alive and was unknowingly raised by adoptive parents.

Ms. Sexton believes her own adoption is suspicious, too: She said her adoptive grandmother was her natural mother’s nurse, and said that while she was born in Ontario, her original birth certificate was from Quebec. She said the Ontario government has no record of her adoption, and that the Quebec government told her the adoption was private. She also said the same doctor is listed on both her and her stillborn sister’s hospital records.

Ms. Sexton’s natural mother declined to participate in the story.

Mr. Whitbourn, the Ontario man born in 1975, said he tracked down his natural mother after registering online at an adoption reunion site. He said she eventually knew to look for him because she received information from the London Children’s Aid Society suggesting her child had been adopted. But one of the society’s adoption supervisors said she finds it “surprising” that a mother would be contacted “out of the blue” with information about a child.

Mr. Whitbourn said he was born healthy but that his mother was told he died overnight. His mother tells him she held her child, then named Jason, just once.

Source: National Post

What the #!%*? Is anybody investigating the allegations of forced adoptions across Canada?

In this occasional feature, the National Post tells you everything you need to know about a complicated issue. Today, Kathryn Blaze Carlson looks at what’s next in the push for an investigation into forced adoptions targeting unmarried women between the 1940s and 1980s.

Q: We’ve been hearing about this issue for weeks. Is anybody investigating?

So far, the United Church and the Salvation Army have announced internal investigations. But because there are mothers in most, if not all, provinces and territories who say they were coerced or forced into giving up their babies, as many as 13 governments could theoretically launch investigations and offer redress; none yet have.

As for other potential probe targets: the allegations span five decades and involve not just governments, but also doctors and nurses who allegedly conspired with social workers to secure illegitimate children for adoption, as well as the churches that ran the maternity homes for unwed mothers.

Q: The Australian Senate just wrapped up a federal inquiry into historic adoption practices there. Any chance Ottawa will follow suit here?

Hard to say. It’s still early in the public push for a federal probe, and so far a spokesperson for Justice Minister Rob Nicholson has said only that adoption is a provincial issue. While that’s true, Valerie Andrews, who heads Origins Canada supporting those separated by adoption, hopes Canada will subscribe to Australia’s view that this is a national issue affecting people across the country.

She might have a champion in the NDP: deputy leader Libby Davies has twice written to Mr. Nicholson asking him to consider a federal inquiry, and justice critic Jack Harris and status of women critic Françoise Boivin recently invited Ms. Andrews to a formal meeting in Ottawa so they can start to “determine what the appropriate response might be.” Ms. Andrews, who is also slated to meet this month with her local Conservative MP, Costas Menegakis, said “maybe somebody is going to listen to us after all.”

Q: If the Conservatives say this is a provincial issue, then what’s happening provincially?