Fatal care: Foster care tragedies cloaked in secrecy

They suffocated in bed, committed suicide, succumbed to disease — 145 Alberta children died in foster care since 1999, and the government hasn’t told you

EDMONTON - The Alberta government has dramatically under-reported the number of child welfare deaths over the past decade, undermining public accountability and thwarting efforts at prevention and reform.

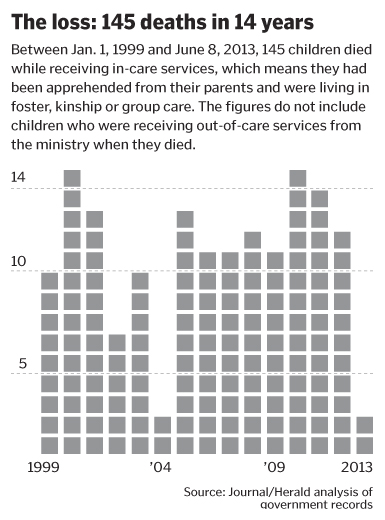

A six-month Edmonton Journal-Calgary Herald investigation found 145 foster children have died since 1999, nearly triple the 56 deaths revealed in government annual reports over the same period.

It is the first definitive count of child welfare fatalities in Alberta, based on death records unsealed by the province after a four-year legal battle. The figure includes all of the children who died in government care after child protection workers apprehended them from their families to keep them safe.

Crucially, however, the count is not yet complete: The ministry has not released death records for at-risk children that the government did not yet apprehend, or for children who were returned to their parents after time in care.

Journalists have identified at least 49 such children. There are likely dozens more.

This startling number of unpublicized deaths highlights the failure of a child death review system blighted by secrecy, disorganization, weak oversight and unmonitored recommendations.

To uncover the number of deaths, the Journal and Herald undertook an unprecedented review of 3,000 pages of ministry death records, historical fatality inquiry reports and lawsuits spanning 14 years.

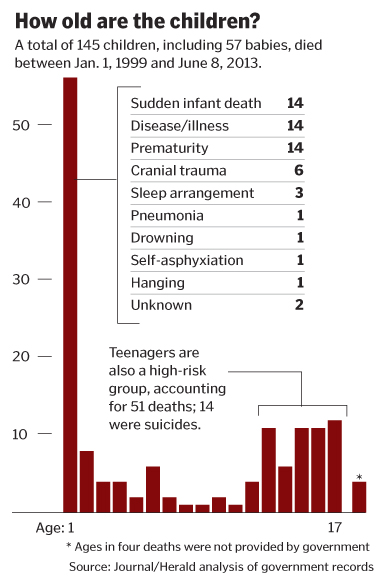

An exhaustive analysis of those documents revealed alarming trends the government has never identified: A third of children who die in care are babies, another third are teenagers, and the vast majority are aboriginal.

These are their stories.

A boy makes a suicide pact with his mother and hangs himself in a group home. A girl is found slain and frozen in a ditch; another drinks herself to death. A mentally ill boy lays down on the railway tracks, his head gets crushed.

More than a dozen babies died inexplicably in their sleep, and many more died from preventable, sleep-related incidents. One died twisted in a foster parent’s bedsheets, another suffocated in a collapsed bassinet, a third succumbed to untreated pneumonia while sleeping on the floor.

Among teens, more than two dozen young aboriginals overdosed on drugs, were beaten or stabbed to death, or committed suicide by hanging from basement rafters, playground equipment and closet bar rods.

Three teens were found frozen outside, including two boys who died of hypothermia in a backyard and a public park. When a 14-year-old girl from the Sunchild First Nation was found frozen in a ditch, officials assumed she, too, had died from hypothermia. An autopsy found she had been killed and dumped. The government made no mention of her death.

Alberta child welfare workers apprehended all of these children from their families, in an effort to protect them from harm. Instead, they died.

(To put the number of deaths into context, there are about 8,500 to 9,000 children in care in Alberta at any one time, according to data from the past five years.)

A fraction of the deaths were subject to investigation, and in cases where reviews were completed, recommendations were not tracked or monitored for implementation.

Alberta has no system for studying trends among children who die in provincial care.

“We owe it to the child victims to not only learn from their tragic deaths, but to prevent such tragedies in the future,” says Gord Phaneuf, chief executive of the Child Welfare League of Canada. “We need to commit to this. There really are no more compelling issues than protecting vulnerable babies, toddlers, children and youth from preventable deaths, and from child maltreatment deaths in particular.”

Phaneuf says governments must study individual deaths in the context of all child deaths, looking to identify which children are most at risk, and why.

“When you start to put the data together, and you do it over extended periods of time, you can discern patterns and trends that tell a very important and compelling story. We need that.”

The Journal and Herald obtained the internal death records through a freedom of information request submitted by the Journal in 2009, that trigged a four-year legal battle. In June 2013, Alberta’s information and privacy commissioner ruled in the Journal’s favour and ordered the province to release death records dating back to Jan. 1, 1999. The records were to include age, ethnicity and circumstances of death for each child, along with recommendations that resulted from the deaths.

This September, the Ministry of Human Services released the internal death records for children who died while receiving in-care services, which means they were apprehended from their families and placed in group homes, foster or kinship care.

The ministry did not release death records for children who were reported to be at risk but were not apprehended, nor did they release death records for children who had been returned to their parents after time in care.

The Journal and Herald’s investigation into failures of the $684-million child intervention system also examined Alberta’s child death review process, and found the process is mired in secrecy and bureaucracy. Dozens of elected officials, political appointees and bureaucrats operate in six different bodies under two different ministries and three different laws.

Recommendations that emerge from these bodies are not binding on government, they are not tracked or monitored for implementation and are not reviewed to see if changes have been effective in preventing child deaths.

People who work inside the system are barred from speaking publicly about their experiences and even the parents of deceased children cannot utter their dead child’s name, for fear of breaking a law that bans the identification of children in care, even after they die.

In the end, the fallout from these deaths is widespread: 12 lawsuits totalling more than $8.7 million, 13 lengthy criminal trials, and the incalculable emotional toll paid by parents, foster parents and child protection workers responsible for children in the care of the state.

Yet in an interview for this series, Human Services Minister Dave Hancock expressed satisfaction with the way the system works. He noted that there are some areas of duplication — and some room for improvement — but overall he concluded that child deaths in Alberta were getting the appropriate amount of investigation and review in the ministry.

“In the death review process,” Hancock said, “we have, I think, a fairly strong organization.”

Source: Edmonton Journal

Editorial: Secrecy in child welfare system fails the powerless

In the middle of a blinding snowstorm, an Edmonton Journal team drove west recently to visit the parents of a First Nations baby who died in care in 2011.

They were not welcomed.

The grieving parents only consented to see the reporter because she had the one thing the government had been denying them for two years.

She knew how their baby lost its life.

The reporter handed them a confidential four-page report, the room fell silent. The parents huddled together, poring over the scant details.

The system had taken away their daughter at birth, and never explained why. Two months later, she was dead and still the callous, dehumanizing silence continued. The parents were denied the autopsy report, the hospital records, all knowledge of the subsequent RCMP investigation.

Knowledge is power, after all, and these are some of the most powerless in our society.

By law, we cannot tell you their names. We cannot tell you their baby’s name.

But today, we can begin to tell you about the 145 children who have died in care in this province since 1999. It took four years and many thousands of dollars in legal bills for the Edmonton Journal to win the battle for these records.

We argued that the public has a right to know about the deaths of society’s most vulnerable and voiceless, so that the child welfare system could be held accountable. The Alberta government argued against the release of this information because, it claimed, the children and their families have a right to privacy.

A publication ban continues to prevent us from identifying the names and faces of these children. More egregiously, it continues to prevent the grieving parents of those children from uttering their dead child’s name in public.

Remember, we must all remember, those two parents we cannot name.

When the Journal finally won this legal battle last June — one in which only a sad and dismayed public could possibly claim victory — Alberta’s Information and Privacy Commissioner ruled that the need for public scrutiny outweighs some privacy protections.

And over the subsequent six-month investigation of these reports by the Journal and the Calgary Herald, many disturbing facts emerged.

The fact that nobody in government could even tell us, at first, how many children had died in care. The fact that the system is so cumbersome and convoluted that no one is accountable for these deaths. The fact that despite hundreds of well-meaning recommendations following fatality inquiries and internal investigations over the years, Albertans cannot see when or if they have been implemented.

Who knew? None of us, obviously.

It’s one of the oldest tricks in the book, using government secrecy and obfuscation to cover inaction, to hide incompetence.

The system has not just failed these children; it has failed us all.

Those involved in the child welfare system are society’s most vulnerable; often its least educated, its poorest, its most powerless. When the system fails them, as it did this blighted family, it is a call to action on the part of those who can and must demand change.

Over the next week, you will hear only the details the government has let us report. We have pursued this because we believe that knowledge is power.

We will remember — we must remember — that this is what it comes down to. Standing up, speaking up, for those who have no name.

Source: Edmonton Journal

Video: Dead in Six Days: The Story of Baby Delonna

Delonna Sullivan was just four months old when she died in April 12, 2011. She had been apprehended from her mother, Jamie Sullivan, by Alberta child welfare officials just six days earlier.

Source: Edmonton Journal

The video Dead in Six Days is on YouTube or local copy (mp4).

Babies account for one-third of all deaths of Alberta foster children

More than half of infants died in their sleep or due to prematurity, yet government has few policies to address these issues

The names of the mother and child in this story have been changed to comply with an Alberta law that prohibits identifying children who have received government care.

LAC LA BICHE — This is what the mother of a dead baby remembers.

The police came and said her six-month-old daughter, Angel, had died in her sleep at her foster home. The mother ran into the bathroom and filled her palms with panicked tears. She did not believe it.

“I remember the house being quiet. It felt like the walls were caving in. I could hear my own heartbeat,” Jodi said. “It was the worst possible thing you could ever feel.”

Her knees buckled at the funeral home when she saw the tiny casket. “I realized then that it was real, that she was going to be in there.”

She remembers picking out a white bonnet to hide the bruises on Angel from when her bassinet collapsed on her, and tucking beaded moccasins into the casket.

One in three children who dies in foster care in Alberta is a baby. In 2009, this six-month-old baby girl died after the bassinet she was sleeping in collapsed. This photo has been altered to comply with Alberta law prohibiting the identification of children in care.

“When I touched her, she was like a rock,” Jodi said. “It was, just, so cold.”

A fire-keeper tended a fire for two days. Elders passed a pipe. Drummers drummed. As she watched the casket descend into the earth, Jodi thought: “My baby is going in the ground, she is going to be alone.”

“The elder said, in Cree, that your grandmother is here and she is taking Angel with her right now. That brought me comfort,” she said.

“But I was so scared that she was by herself, in the dark.”

One in three children who dies in government care in Alberta is a baby, a startling figure given infants account for one in 10 children in care.

Between January 1999 and June 2013, 145 foster children died in Alberta, and 57 of them were babies, a joint Edmonton Journal-Calgary Herald investigation found.

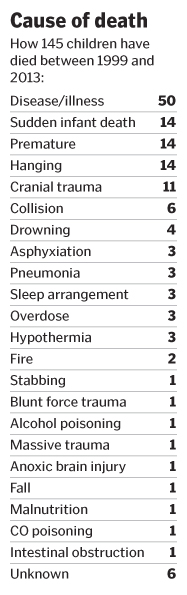

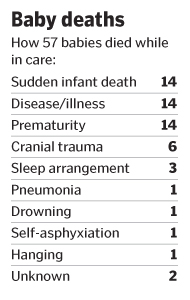

Eighteen died in their sleep, often after a foster parent employed unsafe sleeping practices. Fourteen died from the consequences of premature birth. Another 14 died from chronic illness.

Eight died by accident or homicide, two died for unknown reasons, and one died from untreated pneumonia.

Experts say many of these deaths were preventable, but government has few rules on where and how foster children sleep, and infant deaths related to sleep and prematurity are rarely subject to review.

Instead, fatality inquiries and ministry investigations focus on high-profile homicides and accidents, including a bathtub drowning, a blind cord hanging, and six cases of cranial trauma.

“I haven’t seen anything come back to say there is a systemic issue with infants,” Human Services Minister Dave Hancock said in a recent interview. “Each case is unique and you have to look at it and learn from those cases, and we do.”

The province has no process to study death trends among children in care. “There are only so many, and the people who are involved can fairly easily determine across them what’s happening,” Hancock said.

Angel is one of 18 Alberta foster children who died while sleeping.

At first, police told Jodi that Angel died from Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. She later learned the baby died from “positional asphyxiation” after her bassinet collapsed.

“It was even worse when they told me that she had suffocated,” Jodi said. “She was awake. ... She suffered.”

In six of the deaths, records show foster parents employed what experts call “unsafe sleeping practices,” which increase the odds of sudden death. Such practices include co-sleeping, sleeping on unsafe surfaces such as sofas, sleeping on the stomach or with blankets in the crib.

In 2009, a baby was found face-down in her crib with a blanket around her head. In 2011, a baby died from “self-asphyxiation.” In 2013, a foster mother brought an infant to bed and found the baby tangled in her bedsheets the next morning.

Three infants died during lengthy, unattended naps. Seven were sick, or had recently visited a doctor. In 2009, a baby died of untreated pneumonia while sleeping on a makeshift bed on the floor. In 2011, another died sleeping in an infant carrier with loose sheets — the autopsy concluded: “The infant’s sleep environment was not completely safe.”

In 2003, a foster mother ignored warnings not to put a baby to sleep on his tummy. After the baby died, his doctor said: “That’s probably what killed him.”

By definition, Sudden Infant Death Syndrome is unpredictable; it is listed as a cause of death when doctors cannot find another explanation.

Yet risk factors are well known.

In 2005, a ministry review of eight SIDS deaths found all of the babies showed at least three of those risk factors, including poor prenatal care, maternal smoking, co-sleeping, aboriginal heritage and male gender. A 2011 medical examiner’s report found co-sleeping was a factor in half of all unexplained infant sleeping deaths between 2005 and 2010. A similar 2005 B.C. study found unsafe sleep practices in 83 per cent of infant deaths over 18 months.

Nobody knows why these factors and practices increase SIDS risk, but University of Calgary pediatrics professor Ian Mitchell said that shouldn’t matter.

An 1854 cholera outbreak ceased after a doctor noticed most of the sick drank from the same well, he said. Scientists didn’t yet know about germs, but taking the handle off the water pump stopped the spread.

“When I tell this story, my message for SIDS is that you can stop it without knowing all the fine details. ... Why does quitting smoking work? Why does sleep position work? I don’t know, but it works,” Mitchell said.

Still, rules that govern sleep practices for foster babies are limited.

The safety checklist used for licensing foster parents contains two lines about safe infant sleep: Each child must have a separate bed with a suitable mattress, and cribs or playpens must meet government standards.

Policy requires caseworkers to tell foster parents a crib must be free of pillows and blankets, and foster parents are not allowed to smoke around foster children. However, a safety assessment does not check for these items.

There are no rules about co-sleeping and sleep position, and foster babies are not assessed for SIDS risk.

“When a child is apprehended, you and I are the parents, along with everybody else,” Mitchell said. “The government is now the parent ... The standards have to be the highest possible standards.”

The province has taken some steps to reduce SIDS deaths.

A new Safe Infant Sleep policy comes into effect in January 2014, when health-care professionals will be required to promote universal safe sleep guidelines for all new Alberta mothers. The policy expands on a campaign launched in 2012.

Alberta is also adopting a B.C. program that trains and supports people caring for babies exposed to drugs and alcohol. In 2013, the program was piloted in Edmonton and Saddle Lake, but a provincewide implementation date has not been set.

On Nov. 8, the government announced foster parents who purchase a crib can be reimbursed up to $500.

Jodi was ready for her fourth baby. She set up a crib, bought supplies, saw a doctor and tried to stay sober. She wanted to take her baby home and get her other children back from foster care.

On July 16, 2009, she was on a bus to Edmonton when she realized the baby was coming six weeks early. She walked to the hospital, and Angel came quickly.

“They tested me. I did drink that day, of all days. I drank a six pack to myself,” Jodi said. “They found it in my baby’s system, and my kids before that, that happened, too. So they didn’t even give me a chance to explain.

“I didn’t drink before that, and I decided to drink that day, and then I ended up having her.”

Angel was apprehended at the hospital.

Like 14 babies who died between 1999 and 2013, Angel was premature. It is not clear whether prematurity played a role in her death, but experts say many deaths related to prematurity could be prevented with stronger interventions.

“If you can intervene early enough ... then we really believe we can lower the pre-term birth rate, just through simple behavioural changes,” said David Olson, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Alberta who has studied pregnancy and prematurity for more than 30 years.

Death records for two of the 14 premature babies cite inadequate prenatal care as a factor in the child’s death.

Officials say government cannot legally intervene until a child is born, but the ministry offers voluntary prenatal support to expectant mothers. Some women who have had children with fetal alcohol disorder can take part in a three-year, home visitation program shown to reduce substance abuse and increase use of birth control.

A U.S. program that brings at-risk mothers together for monthly meetings on prenatal care resulted in a 33-per-cent reduction in premature births, according to a 2007 study in the Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Olson said.

Alberta government investigations into prematurity and sleep deaths are rare.

A policy in effect until 2009 automatically ruled out an in-depth internal review when a child died for medical reasons; current policies are not documented.

Between 1999 and 2010, no fatality inquiries into sleep deaths occurred. Since then, the province has called six such inquiries. Two are scheduled for 2014, including Angel’s.

The internal summary of her case was completed in August 2010. It noted bassinets in Canada were unregulated and the ministry had no policy for their use. Since then, Health Canada has passed stringent regulations. The ministry still has no policy.

The review also revealed Angel slept in the bassinet for six months because she had no crib — a clear violation that went unaddressed.

The report reiterates foster children must have their own bed, and says “this does not include hammocks, bassinets or playpens.” The report was never made public, and this prohibition is not reflected in policy.

Jodi shared her story because she doesn’t want other parents to suffer. Her life has unravelled since Angel died. She continues to struggle with alcoholism. The pain and guilt are insurmountable.

This is what she wants to remember:

“She was wise, in her eyes,” she says of Angel. “The last time I saw her, when I put her down to put her stuff on her, she grabbed my pinkies and she wouldn’t let go.

“She was saying goodbye to me.”

About this data analysis

It is impossible to make an apples-to-apples comparison of the mortality rate between infants overall in Alberta and those in provincial care.

This is partly because the infant mortality rate is calculated by using the number of births and deaths over a set period of time; by contrast, the number of infants in care changes from month to month.

It is also because the data that underpins this story is based on incomplete death records released by the provincial government after a four-year legal battle with the Edmonton Journal.

When possible, we extracted key details from the records, including the child’s age, but in many cases, the government provided only the years of birth and death. In these cases, we calculated ages based on a birth and death date of Jan. 1, which results in imprecise ages.

With this context, it is worth noting that the mortality rate for Alberta-born infants under one year was 1.6 per 1,000 live births between 2001 and 2010 — the most comparable figures available.

As of September 2013, there were 830 children in care in Alberta under 18 months old. Our data shows that on average, between 1999 and 2012, four infants died in care per year. Taken together, the death rate of infants in care is 4.8 per 1,000 apprehensions.

Source: Edmonton Journal

Deaths of Alberta aboriginal children in care no ‘fluke of statistics’

More likely to die of accidents, suicide and homicide; children also more at risk if under care of federally funded on-reserve agencies

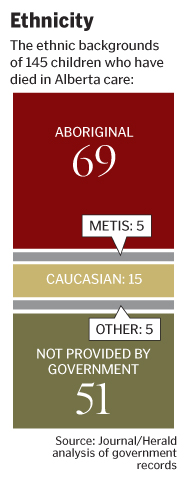

Only nine per cent of Alberta children are aboriginal, yet they account for a staggering 78 per cent of children who have died in foster care since 1999.

Aboriginal children are also more likely to die if they are put in foster care on reserve, a statistic that starkly highlights the federal/provincial funding disparity that gives off-reserve aboriginal children more services and more support.

According to an Edmonton Journal-Calgary Herald investigation, 145 children in Alberta have died in foster care since 1999. Of the 145, the provincial government lists ethnic information for 94 children, including 74 who were aboriginal.

Among the findings:

- 31 of the 74 aboriginal children who died were in their teens; of those, 25 were aged 15 to 17.

- 24 were infants; of those, 10 of them died from SIDS or from the consequences of prematurity.

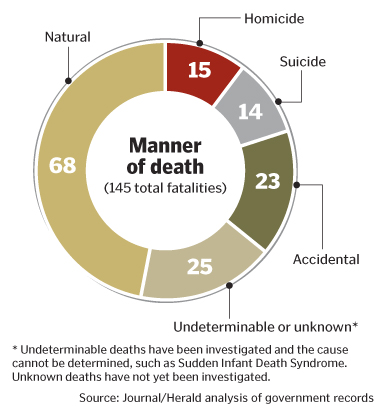

- 13 aboriginal children died in accidents; 12 committed suicide, 10 were the victims of homicide.

- 45 aboriginal children died in the care of a provincially funded Children and Family Services Agency (CFSA) while 29 died in the care of an on-reserve Delegated First Nations Agencies (DFNA). However, DFNAs care for a fraction of the children that CFSAs do — in 2012-2013, 73 per cent of aboriginal children were in the care of a CFSA, 27 per cent in a DFNA. Therefore, since 1999, proportionately more children died in the care of a DFNA than a CFSA.

“There are an incredible number of kids dying in care each year,” said Raven Sinclair, an aboriginal professor who teaches in the faculty of social work at the University of Regina. “This isn’t just an accident. It is not a fluke of statistics. It is happening year after year.”

Experts blame the disproportionate rate of aboriginal children dying in care on poverty, substance abuse, substandard housing, the legacy of residential schools and a lack of supports and services in aboriginal communities.

Critical to the argument is a funding disparity between on- and off-reserve agencies.

In the early 1970s, Alberta First Nations began establishing their own on-reserve child welfare agencies, with the first on the Siksika First Nation in southern Alberta in 1973. Since then, the province has signed 17 additional agreements with 40 of Alberta’s 47 First Nations. These Delegated First Nations Agencies are funded by Ottawa, but regulated by Alberta.

They take care of children on reserves; those who are off-reserve are taken care of by the provincially funded Children and Family Services Agencies.

According to Jean Lafrance, a former Alberta child advocate and children’s services assistant deputy minister, the government hoped delegating responsibility for First Nations children to aboriginal agencies on-reserve would result in more culturally appropriate programs, and reduce the apprehensions of children, but that hasn’t happened.

In many ways, the transition hasn’t been smooth. In 2002, a DFNA was temporarily suspended after a series of deaths; the province had to provide mentors for aboriginal caseworkers and help the understaffed agency with high caseloads. Band leaders have taken active roles in apprehensions and staffing decisions, and funds for child welfare services have been misspent.

And there have been repeated complaints about lack of funding.

Cindy Blackstock, executive director of the First Nations Family and Child Caring Society and an associate professor at the University of Alberta, says aboriginal agencies receive about 22 per cent less in funding than provincial agencies. Her organization and the Assembly of First Nations took the matter to the Canadian Human Rights Commission in 2007. That case is still ongoing.

“It is shocking to many people that in this day and age on the heels of the residential school fiasco that we have the government of Canada on trial for racial discrimination, simply to get it to do what it should do as part of a moral course, which is to provide equitable funding for these children and their families and give them a fighting chance at growing up safely in their homes,” Blackstock said.

First Nations agencies argue the federal funding is flawed because it is based on the formula that six per cent of children on reserves will need child welfare services. In reality, the rate of children in care can be as high as 18 per cent.

The federal government has since boosted funding for preventive services with an enhanced funding formula, but First Nations and the federal auditor general have said it still doesn’t match the province’s level of agencies funding.

Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada spokeswoman Valérie Haché said the department has boosted funding for aboriginal child welfare agencies nationally from $193 million in 1996-1997 to approximately $618 million in 2011-2012, plus an additional $374 million in enhanced prevention focused funding.

Alberta DFNAs have received $98 million since 2007 and are slated to receive $20 million this year, she said.

“Improving the safety and well-being of First Nations children on reserve and child welfare services on reserve is a priority for our government,” she said in an email.

But a 2010 evaluation of the enhanced funding could not determine whether the program is delivering reasonably comparable services to those provided by provincial agencies, or whether the additional funding is reducing the apprehensions of aboriginal children.

Delegated First Nations Agencies simply haven’t been able to afford the same level of services of CFSAs, such as programs to keep kids at home with their parents.

“If you had a family facing very serious problems, problems that might be solved by providing parenting programs, maybe a homemaker, maybe a child-care worker — those kind of services which are available for all children across Alberta through regular child welfare authorities were not being funded by the federal government until fairly recently,” said Nico Trocme, a McGill University professor of social work. Statistics from the Ministry of Human Services seem to bear that out, showing far more non-aboriginal children receive home supports than aboriginal children.

According to 2012-13 figures, a total of 12,032 children in Alberta were receiving intervention services, either in the care of the government or in their family home. Aboriginal children made up 7,027 of that number; 82 per cent of them had been apprehended, while 18 per cent were receiving services at home.

In comparison, of the 5,005 non-aboriginal children in the system, only 54 per cent had been apprehended, while 46 per cent were receiving services at home.

The issue has been raised at two recent fatality inquiries in Alberta.

Carolyn Peacock, executive director of Kasohkowew Children’s Society on the Samson First Nation at Hobbema, told a September inquiry federal funding doesn’t cover programs for children with fetal alcohol syndrome or other disabilities on the reserve.

Alberta provincial court Judge Bart Rosborough raised similar concerns in a report into another death. “I recommend that Alberta investigate whether such a disparity exists and, if so, enter into consultations with Canada to eliminate that disparity.”

The funding issue also results in staffing and training issues on reserves, including high caseloads and lack of supervision, which can lead to deaths.

“Child protection is failing our kids because child protection doesn’t have the resources to effectively monitor what is going on in foster care and group care,” said University of Victoria associate professor Jeannine Carriere, who has been contracted by Alberta in the past to review aboriginal deaths in care.

University of British Columbia assistant professor Shelly Johnson concurs: “We have foster parents that are quite poorly supported and social workers are desperate to place very high needs children in homes where foster parents may not have adequate training support.”

Johnson, who headed a First Nations children’s services agency in Victoria, adds:

“I don’t think the answer is turning over a broken and flawed system and then paying aboriginal people 22 per cent less than everybody else to manage that misery.”

Indeed, First Nations agencies blame high staff turnover on the simple fact they can’t afford to match provincial caseworkers’ salaries.

Darrin Keewatin, a former director of Kasohkowew Child Wellness Society in Hobbema, told the human rights tribunal his caseworkers often handled up to 35 cases compared to 20 for their provincial counterparts.

He also noted that — using the new money from the federal government — he hired three workers to do prevention work with at-risk families on the Samson First Nation, but ended up retraining them as front-line caseworkers due to chronic staffing issues. This problem was exacerbated by the fact his DFNA has to place many children with high medical needs in private facilities and group homes off-reserve.

“First Nations children in Alberta are the walking barrels of oil to those group homes and institutions,” he said. “If all of my money is going to group care, how can I begin to develop a prevention program or do family counselling or any services?”

Human Services Minister Dave Hancock said his government is working with the chiefs from the province’s three regional treaty areas on the funding issue.

“All children in Alberta are Alberta children and jurisdiction should not get in the way of appropriate service delivery,” he said in a recent interview.

A move in 2004 to involve a person designated by the First Nation band council to help plan for a child’s services has made a difference, he said. But Hancock conceded the over-representation of aboriginal care won’t be resolved quickly.

Mark Hattori, assistant deputy minister of the child and family services division of Alberta Human Services, agreed that the province must work in partnership with aboriginal people to reduce the number of aboriginal children in care.

“Can we do a better job? Absolutely,” he said. “We don’t deny that there are things that need to be changed.”

With files from Karen Kleiss, Edmonton Journal

About this data analysis

Our analysis of the deaths of aboriginal children in care is restricted by the incomplete data released to us by the Ministry of Human Services.

Of the ministry’s death records for the 145 children who died in care between Jan. 1, 1999 and June 8, 2013, only 94 recorded ethnicity; 69 of which were aboriginal and five were recorded as Métis. Another 15 were Caucasian, and five were listed as “other,” but a total of 51 had no ethnicity listed.

Therefore, when we refer to the percentage of aboriginal deaths compared to the total deaths, we are using only those cases for which ethnicity is known.

To put the number of deaths into context, there are about 8,500 to 9,000 children in the care of the Alberta government at any one time, according to data from the past five years.

We also asked the province for data on the number of aboriginal children being cared for by a provincially operated Child and Family Services Authority (CFSA) or a Delegated First Nation Agency (DFNA).

The ministry reported that in 2012-13, 7,027 aboriginal children were receiving intervention services from the government — 5,769 were in care, while another 1,258 hadn’t been apprehended but were receiving help.

Of that total, 73 per cent of them, or 5,130, were in the care of a CFSA. The remaining 27 per cent, or 1,897, were in a DFNA.

Using the ethnic data that we know, we calculated that 74 aboriginal children died in care since Jan. 1, 1999, 45 in a CFSA and 29 in a DFNA. Applying the ratio of 73 per cent in a CFSA to 27 per cent in a DFNA, we calculated that on average, 3.4 aboriginal children died annually in a CFSA, and 2.4 aboriginal children died annually in a DFNA.

In applying those numbers to the 2013 figures, the result is a death rate of aboriginal children of 0.66/1,000 in the care of a CFSA, and a rate of 1.26/1,000 in the care of a DFNA.

Clearly, there are limitations to this data analysis. First, we do not have the ethnicities of all the deceased children. Second, we used 2012-13 figures to create an average rate, yet the percentage of children in a CFSA versus a DFNA could certainly have changed over the years. We did not have that information.

Finally, it’s difficult to compare the percentage of the deceased children in care who are aboriginal with the percentage of children in care who are aboriginal. That’s because the makeup of the in-care population has changed over the years.

For example, between 2008 and 2013, the percentage of children in care who were aboriginal rose from 60 per cent to 68 per cent. While the actual number has increased by only about 400 children, the percentage appears greater due to a drop in non-aboriginal children in care.

Source: Edmonton Journal

Alberta’s child death review system lacks accountability, transparency, clear mandate

Even when reviews are done, there’s no process to track, implement proposals

Alberta’s tangled system for investigating the deaths of foster children is secretive, redundant and fails to ensure recommendations to prevent similar deaths are acted upon, an Edmonton Journal-Calgary Herald investigation has found.

The child death review system is governed by two ministries, three different laws, an internal policy document, unwritten conventions and political whim.

At least six groups with divergent mandates review some or all child welfare deaths, depending on the laws that govern them. Communication between organizations is limited and sometimes litigious, conclusions are drawn in isolation, and recommendations can be radically different.

The decision to investigate is made largely in secret, with limited public accountability, despite at least three government-funded reports calling for independent, transparent oversight.

Just two of the six organizations have published guidelines that dictate which deaths must be reviewed, and none is required to tell the public why they decided for or against an investigation.

There is no appeal process for parents or advocates who believe a child’s death has not been adequately scrutinized.

In the end, many deaths are never investigated at all. These include the case of a 13-year-old boy who had a seizure and drowned in a bathtub in 2000, the death of a 17-year-old girl from a massive cocaine overdose in 2002, the drowning of 17-year-old boy in a river in 2007, the alcohol poisoning death of a 14-year-old girl in 2008, a 14-year-old boy found frozen to death in 2009, and more than a dozen babies who died in their sleep.

Of the 145 children who died in the care of the Alberta government between 1999 and 2013, 53 cases merited a public fatality inquiry or a documented in-depth internal review. When those reviews issued recommendations to prevent future deaths, there was no system in place to track them, or to ensure they were implemented.

SO, HOW DID WE GET HERE?

In June 1977, the province passed the Fatality Inquiries Act, authorizing medical examiners to investigate all sudden deaths, including child welfare deaths. The act also established the fatality review board, whose job would be to recommend which deaths should be the subject of a fatality inquiry led by provincial court judge.

The objective of the law, which remains the cornerstone of Alberta’s child death review system, was not to assign blame, but to prevent future deaths.

In the intervening decades, however, new ideas emerged about how to investigate, learn from and prevent child deaths.

Now, many experts say the most effective reviews are conducted by an independent multi-disciplinary group of professionals that includes pediatricians, child welfare experts and police.

They argue the system should be transparent, with clear guidelines about who investigates deaths, and why. Findings should be made public and the resulting changes should be monitored to make sure they are effective.

Such a system would reveal trends that could result in targeted improvements that save children’s lives, said Gord Phaneuf, executive director of the Child Welfare League of Canada.

“When we look at (deaths) in isolation, as individual occurrences, the tendency is to miss the larger significance, particularly when we want to think from a prevention perspective,” Phaneuf said. “To really get a meaningful understanding of the risk factors … you have to look at more than one case. You look at many cases.”

In response to the changing philosophy, the Alberta government has added to its system, tacking on advocates, panels and committees, but not overhauling it.

First came the child and youth advocate in 1989, a position intended to give a voice to wards of the province. In the mid-1990s, the medical examiner established pediatric death review committees to look at child deaths under 18, including children in care.

By the early 2000s, the ministry was conducting internal special case reviews into child welfare deaths, which were overseen by a panel of department experts, but weren’t made public.

In 2005, the government changed the Fatality Inquiries Act to make it “as efficient and effective as possible,” by reducing the number of inquiries into child welfare deaths and restricting media access.

In August 2011, the province established the internal council for quality assurance, and months later newly elected Premier Alison Redford made the child and youth advocate an independent officer of the legislature. Both now have the power to order independent investigations into systemic issues arising from a child’s death.

Most of these changes were made under political fire, during an election campaign or after a tragedy made headlines.

COMMUNICATION PROBLEMS, OVERLAP

The result is a circuitous child death review system plagued by duplication and poor communication.

Officials at the helm of all six main bodies say their organizations are independent from each other and that they rarely share information; in some cases, agencies employ lawyers before sharing records.

Pediatrician Lionel Dibden, chairman of the council for quality assurance, said the council defers to Del Graff, the child and youth advocate, to investigate systemic issues and doesn’t focus on reviewing child welfare deaths; members have the power to do both, but he wants to avoid further duplication.

He notes reviews are already conducted by the advocate, the fatality review board, the medical examiner’s office and the pediatric death review committee. In addition, some deaths trigger a fatality inquiry and others are subject to criminal investigation.

“Many of them relate to the same question,” Dibden said. “What happened? … What went wrong, or not wrong, and what can we learn from that?

“Alas, it always seemed to me that there was a lot of overlap. People are doing the same thing, trying to do it at the same time, then there were timelines that you couldn’t do one thing before you did the other,” he said. “My position was, whatever we do, we should not make it worse by duplicating what other people are doing.”

Instead, he said the council has set up a spreadsheet to track the “myriad” reviews underway, and focuses on working with government to improve the system in other ways.

Human Services Minister Dave Hancock acknowledges the system retraces its own steps.

“Typically, a fatality review report is about five years after an incident,” he said. “It is almost a retrospective check back to say — and that’s not to say that they’re not important, they are important — to make sure we caught everything.

“But by the time it comes out, I hope that my answer would be, yes, we have already dealt with that.”

The system, he said, meets his expectations.

“My expectations would be that first and foremost we would learn everything we possibly could from any incident. ... Out of every circumstance, we should learn,” said Hancock.

“In the death review process, we have, I think, a fairly strong organization.”

Hancock and Justice Minister Jonathan Denis together oversee a child death review system governed by three different laws, each of which uses a different legal definition of what constitutes a reviewable death.

As a result, there is no single person or agency that is accountable for the system, and each body is entitled to information about a different subset of deaths.

The medical examiner and quality assurance council are only legally entitled to information about the deaths of children receiving in-care services — these are children who have been apprehended from their parents.

The fatality review board also reviews deaths in care, but only if the cause of death was unnatural or undetermined, or if the child died under suspicious circumstances.

The law is silent about which deaths the pediatric death review committee examines.

Only the child and youth advocate is entitled to information about all child welfare deaths, including at-risk children who were known to the ministry but not taken into foster care.

FEWER REVIEWS

The changes have also resulted in fewer opportunities to investigate what went wrong in an individual child’s case.

While the medical examiner continues to look at individual deaths in care, all other avenues for individual reviews are closed or significantly reduced.

The quality assurance council and the office of the child and youth advocate review child deaths when there are systemic issues at play.

The pediatric death review committee examines individual deaths, but work was suspended in September 2013, pending review. Chief medical examiner Anny Sauvageau declined interview requests, but a spokeswoman said the review is expected to be finished in 2014, after which a new model will put in place. She declined to say what the model would look like.

Until 2009, the Ministry of Human Services conducted special case reviews into individual child deaths that were unexpected or preventable. These internal reviews included interviews with key people, oversight by an internal panel of experts, and recommendations for change. The process was governed by written guidelines and captured 20 of the 145 in-care deaths between 1999 and 2013.

But the number plummeted in the 2000s — from seven in 2001 to one in 2009 — and they have since been stopped.

Mark Hattori, assistant deputy minister of human services, said such reviews have been replaced with an informal process that doesn’t result in written recommendations.

“There might be some conversations between the statutory director and their staff ... but we don’t necessarily create reports,” Hattori said. “It wouldn’t be documented. ... Some of it might be meetings; there may not be minutes.”

The lone document produced during the new internal review is a chronology of the dead child’s time in care, Hattori said.

Today, a fatality inquiry is the only part of Alberta’s child death review system that conducts a documented, public review of an individual child’s death, but the number of fatality inquiries has fallen dramatically in recent years.

Until 2005, the law required the fatality review board to recommend an inquiry into every death in care, unless the board was convinced the death was both natural and unpreventable.

In 2005, the law was changed, and now, the board can avert an inquiry if it sees “no meaningful connection” between the child’s death and the quality of care. At the time of the law change, critics said the board couldn’t possibly know whether the quality of care played a role in the child’s death without a fatality inquiry, and warned the change would reduce the number of inquiries into deaths in care.

Indeed, in the 15 years that preceded the law change, there was an average of three inquiries a year into the deaths of children in care. In the four years that followed the change, the average was fewer than one. In 2006 and 2008, there were none.

Those statistics were contained in annual reports issued by the medical examiner’s office, but the office stopped publishing such reports in 2009.

RECOMMENDATIONS NOT TRACKED

When reviews are completed, the recommendations that emerge are not collected, tracked or monitored for implementation. None are binding on government, and the province is not required to respond.

Internal and historical recommendations are not accessible to the public.

Since 1999, fatality inquiries and internal reviews have together resulted in 258 recommendations, in addition to those from the child and youth advocate, the auditor general and one-of-a-kind expert panels.

In August, the quality assurance council wrote a letter to Hancock recommending the province collect and monitor recommendations from these reviews.

The ministry refused to release the letter, but Hancock said the government has agreed to “a more formal tracking process” that would be publicly accessible online.

Still, he said he’s confident the ministry has thus far appropriately implemented recommendations and that the government’s “system” would alert him if recommendations were being repeated.

Pressed to explain how, Hancock said: “The people who are involved actually, there are not so many (deaths) that they don’t know each one fairly well. And they would know what’s coming out of them. I am confident that we actually do a pretty good job — I think, an excellent job — of learning from each circumstance and tying them together.”

Source: Edmonton Journal

Restrictive law silences grieving parents

Publication ban prohibits naming deceased children, shields Alberta government from scrutiny

Alberta’s ban on publicizing the names and photos of children who die in provincial care is one of the most restrictive in the country, robbing grieving families of their ability to raise concerns in public about the deaths and sheltering government officials from scrutiny.

About 10 children die in care in Alberta every year, but because of a law that prevents their names and photographs — and those of parents or guardians — from being publicized, the public is denied the right to know who they are and assess whether their deaths could have been prevented.

Basic information about the 145 children who died in care in Alberta between 1999 and 2013 was only released to the Edmonton Journal and Calgary Herald after a four-year legal battle. Still, we can only tell you the names of two of the 145. That’s because their parents applied in court to have the publication ban lifted — a step all parents must take if they wish to speak out about the deaths of their children.

Velvet Martin, who went through the court process, said the ban is evil and “the nemesis of justice.”

“They have failed the child in the utmost way possible and now they are stealing their identity — the only thing they have left,” said Martin, whose daughter Samantha died after being in care. “It’s bad enough to lose a child, but to have it covered up is just wrong and I won’t stand for it.”

With scant information on child death cases, Albertans are left to trust that the government will investigate and correct any systemic problems, yet often the same people responsible for supervising a case lead the review.

The result of the legislation is a blanket of confidentiality over the child welfare system.

Child welfare agencies won’t talk to the media. Several didn’t respond to repeated requests for information about how they protect children and one, citing the province’s privacy act, referred calls to the Ministry of Human Services.

People who work inside the system are barred from speaking publicly about their experiences; even those who spoke on condition of anonymity were afraid they’d lose their jobs.

Government officials argue the ban is necessary to protect the privacy of children and their families; in some cases, a child who dies might have siblings who are also in government care. Children in care are some of the province’s most vulnerable citizens, and provincial authorities feel strongly about trying to protect them.

“I think there is always a balance of values that you have to take into account,” said Human Services Minister Dave Hancock. “One of the values obviously is an open and transparent process so that people can know and understand what is happening and know that things are being handled in an appropriate fashion. The other value is you don’t want to intrude in the personal lives of families any more than necessary, particularly in circumstances like that where they have already suffered significant tragedy.”

In a press conference on Wednesday, in response to the Journal-Herald investigation, Hancock said that the issue of where that line should be drawn will be discussed at a roundtable of MLAs and experts scheduled for January. Hancock announced the roundtable on Tuesday.

The Alberta College of Social Workers supports the principle of the ban for the benefit of the family and any siblings.

“It could cause some definite hardship for the family,” said spokeswoman Lori Sigurdson. “They could be ostracized in the community. It could be a shame thing. Their relationship with the ministry and the worker who is working with them could become antagonistic or more difficult because they feel they have betrayed them.”

Hancock said the bodies that review deaths — including the child and youth advocate, the quality assurance council and the fatality inquiry review board — provide the public with appropriate access to information. He said it’s “not necessarily useful to publish a name and face just for the prurient interest of the opposition or others.”

However, in an interview this month, Hancock admitted he didn’t realize the law went so far as to prohibit parents from talking about their children and releasing their names to the media, and said he would look into it.

“I think families for the most part need to be able to heal and need to have the discussions that they need to heal,” he said.

That’s the argument made by the family of a 21-month-old aboriginal baby who died in a foster home in 2010.

“It is ridiculous. We want to tell our story and we can’t,” the girl’s aunt said. “We’re suffering in silence here.”

A Morinville foster mother has been charged with second-degree murder, but the case has not yet gone to trial. It could be years before the facts of the case and what went wrong are revealed — if ever.

Choking back tears, the aunt said problems with the system must be scrutinized if similar deaths are to be avoided. “Every couple of years, another child is dying in care, and it is usually a native kid,” she said.

Martin, the mother who had the ban lifted on her daughter’s name, said almost every family she has met wants to speak out, but they often don’t know their rights and can’t afford to seek legal advice.

“A lot of people don’t have the fortitude, they don’t have the education, the ability, to come forward,” said Martin, a spokeswoman for a national advocacy group called Protecting Canadian Children.

In her case, she was able to lobby for a fatality inquiry. During that process, she found out that while Samantha’s caseworker had assured her that the girl — who had a number of medical conditions — was getting exceptional care, the caseworker hadn’t seen her for 14 months, nor had she been examined by a doctor in three years.

“I was naive and under the impression that children’s services was doing an internal investigation and were actually going to do something other than cover their ass,” she said. “It was a hard lesson for me.”

Like Martin, Jamie Sullivan went to court to lift the ban on her daughter Delonna’s name — but she’s angry she had to. “If you want to arrest me for talking about my daughter, then arrest me,” she said. “You can’t take anything more from me than you have already. ... And I’m not going to have somebody telling me I can’t show her picture. That’s just not right.”

The publication ban law is part of Alberta’s Child, Youth and Family Enhancement Act. It stipulates that “no person shall publish the name or a photograph of a child or of the child’s parent or guardian in a manner that reveals that the child is receiving or has received intervention services.” The penalty is a maximum $10,000 fine or up to six months in jail.

Prior to legislative changes in 2004, the ban didn’t exist. A 13-member task force, chaired by Calgary MLA Harvey Cenaiko and made up entirely of Conservative MLAs and child welfare officials, had recommended the change to government. Cenaiko told MLAs the new provisions were drafted to align with the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act. No mention was made that the ban remained in place after a child died.

Provincial privacy commissioner Jill Clayton, who wasn’t in office when the law was amended, said she can’t find any record of the government consulting the office for advice or guidance on the issue.

Across Canada, most provinces ban the publication of names of children who are in care or receiving services from the government, but lift the ban or decline to enforce it when one of those children die. Only Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Quebec have bans similar to Alberta’s, and officials say Quebec currently does not enforce the ban when a child dies.

But in Alberta, despite the minister’s promise to review the ban, the government continues to enforce it.

This month, Alberta’s children services director refused a request from the Journal and Herald to lift the ban on the name of a Samson Cree baby, opposing an application that was supported with affidavits from both the child’s parents.

Being able to publish the names, photographs and personal stories of children who die in care are large factors in bringing about change, experts say. If parents are muzzled, there is no one else to speak for the children, said Robert Fellmeth, executive director of the Children’s Advocacy Institute in the U.S.

“These children have no lobby,” said Fellmouth, a professor of public interest law at the University of San Diego. “They have no campaign contributions. They don’t vote. Their sole asset is democracy, and public sympathy and concern, and disclosure. That’s the sole political card they have.”

Many laws to protect children are named after child victims, he noted. The Amber Alert system was named for Amber Hagerman, a nine-year-old abducted and murdered in Arlington, Texas, in 1996, while Chelsea’s Law in California, which increases penalties and monitoring of sexual offenders, was named after 17-year-old rape-murder victim Chelsea King.

In Canada, there’s the Jordan Principle that stipulates that care be provided for children when they need it and decisions about who is responsible for paying for it be made later. It is named after a five-year-old Manitoba Cree child named Jordan River Anderson, who died in hospital while federal and provincial authorities bickered over who was responsible for his home care.

And in other provinces, the deaths of children in care make headlines. In Manitoba, a public inquiry has put the 2005 death of five-year-old Phoenix Sinclair under the microscope; in Saskatchewan, RCMP are investigating the alleged 2013 murder of six-year-old Lee Bonneau by another child under the age of 12; and in Ontario, an inquiry has been probing the case of five-year-old Jeffrey Baldwin, who died in 2002 after years of mistreatment.

By comparison, in Alberta, when the child and youth advocate writes reports about flaws in the system, he has to make up names for the children. In July, he released “Remembering Brian,” and just last week he issued “Kamil: An Immigrant Youth’s Struggle.” Both are pseudonyms.

Even when a death of a child in care is examined at a fatality inquiry in Alberta, the children and parents are identified only by initials. Provincial court Judge Leonard Mandamin balked at this practice in an August 2007 fatality inquiry report into the suicide of a 16-year-old Tsuu T’ina boy. “The use of initials dehumanizes the tragic death of this young person,” he wrote.

University of Manitoba professor Arthur Schafer, director of the Centre for Professional and Applied Ethics, wonders who the publication law is designed to protect.

“My overarching concern is that privacy is being used as a smokescreen to conceal potential wrongdoing and to prevent the public from getting an accurate picture of problems that may turn out to be systemic,” he said. “Privacy considerations are important, but they aren’t absolute.”

Publication bans by province

British Columbia: The name and photo of a child who dies in care can be published provided information comes from family or other sources.

Alberta: It is illegal to publish names or photos of children who die in care without a court order lifting the ban.

Saskatchewan: The name and photo of a child who dies in care can be published provided information comes from family.

Manitoba: The name and photo of a child who dies in care can be published provided information comes from family.

Ontario: The name and photo of a child who dies in care can be published without restriction.

Quebec: It is illegal to publish the name and photo of a child who dies in care, but the law is not enforced.

New Brunswick: It is illegal to publish the name of a child who dies in care.

Nova Scotia: It is illegal to publish the name of a child who dies in care.

Prince Edward Island: The name and photo of a child who dies in care can be published.

Newfoundland and Labrador: The name and photo of a child who dies in care can be published if information comes from family or other sources.

Source: Edmonton Journal

Simons: When accused killers have no faces — Baby M case poses complex moral questions

EDMONTON - Thursday morning, the Supreme Court of Canada will reveal whether it will hear the Baby M case.

In May of 2012, M’s parents, immigrants from Algeria, were charged with aggravated assault. The couple had a three-year-old son and two-year-old twin daughters, M and her sister.

Under the terms of the province’s strict Child, Youth and Family Enhancement Act, we are forbidden to identify any of them.

According to court documents, all three children had allegedly been abused or traumatized in some way. But the girls allegedly suffered more. M was the most badly hurt. Profound brain damage that left her paralyzed, unable to breathe. She was placed on life support.

All three children were taken into the care of Children’s Services. But as the months went by it was apparent that M would never recover. Her brain had liquefied. Doctors wanted to end the extraordinary measures artificially prolonging her life. Her Muslim parents refused, citing their religious beliefs.

But they also faced murder charges if the child died.

In the fall of 2012, Alberta Human Services went to court to ask a judge to make a decision about M’s fate.

Justice June Ross ruled that the child should be taken off life support. The parents’ lawyers sought an emergency appeal. The Court of Appeal upheld Ross’s ruling. The parents appealed again to the Supreme Court in Ottawa, but a special three-judge panel refused to grant an emergency stay of Ross’s order.

M was removed from the ventilator and died shortly afterwards. Her parents were subsequently charged with murder. They’re still at the Remand Centre, where they’ve been held for the last 19 months. Their trial is scheduled for next May, two years after they were first arrested.

Yet the Supreme Court appeal process is still very much alive. Despite the fact that M died in September of 2012, the court has been asked to hear arguments on the difficult legal question, “Who should decide when a dying child should be removed from life support?” The Crown? The courts? The doctors? Or the parents?

We’ll find out early Thursday morning whether the court will hear the appeal and establish a national precedent, or whether the Alberta rulings will stand.

Whatever the Supreme Court decides, under provincial law, we’ll never be able to identify M or her parents.

In theory, that’s to protect the identities of M’s siblings. In reality, it creates a problematic situation for M’s parents.

For almost two years, they’ve been locked away out of sight, out of mind. Because we could never name them, never show you a court sketch, they’ve remained faceless, anonymous monsters. There’s been no way to humanize them or tell their complicated story. It’s been all too easy for some to project their Islamophobia or racism on the couple because they’ve been ciphers, symbols, and never real people.

It’s the same situation for many, many of the foster parents or kinship care providers who’ve been charged with murder or manslaughter in the deaths of kids in care.

Remember SC, the young aunt convicted of manslaughter in the death of her niece, JC? Or little BL, shaken to death by his cousin’s common-law partner?

Probably not.

Like K, the hero of Kakfa’s The Castle, they’re all initials, not people.

The provincial Child, Youth and Family Enhancement Act trumps the federal Criminal Code. It leads to quasi-secret trials in which neither the accused nor the victims have names or faces.

By contrast, consider the well-publicized cases of Allyson McConnell and Nerlin Sarmiento, two troubled mothers who drowned their young sons. We saw their faces and the faces of their lost boys. They weren’t shielded from public judgment by anonymity. But McConnell’s mother and Sarmiento’s husband could speak to the media, offering context and explanation for their loved one’s apparently inexplicable acts. McConnell, who later killed herself, was found guilty of manslaughter. Sarmiento was found not criminally responsible.

The public could critique the fairness of those verdicts because we knew the complex stories. To us, they’d become real people.

The accused and convicted killers who are tried anonymously never really are. Neither are their victims. That doesn’t serve the interests of justice, and it violates the fundamental principles of the open court system.

We do need to safeguard the privacy of living children in care. But we need a better balance, one that doesn’t fetishize “privacy” at the expense of the right to a fair trial — or the right to freedom of expression.

Source: Edmonton Journal

Photos: Living, dying in the shadows

Since 1999, 145 children have died in foster care in Alberta. But a provincial law won’t let us name them, or show you their faces. These are some of those children.

Source: Edmonton Journal

The price of a flawed child welfare system? $8.7 million in claims

At least 12 families have sued the Alberta government over deaths of children in care

Names in this story have been changed to comply with an Alberta law that prohibits identifying children who have received government care.

PAUL FIRST NATION — In a sudden, sickening instant, Sarah knew they were going to take her baby.

She was lying in a hospital bed with her newborn daughter, Amy, just 10 hours old. The baby started fussing and she asked the child protection workers to leave for a moment, so she could breastfeed. They refused.

“The woman said ... ‘I’ll get a nurse to bring her in a bottle’,” Sarah said. “I looked at her and I said, ‘I’m trying to breastfeed my baby, and you want me to give her a bottle?’ By then I was already upset.

“They knew they were going to take her.”

Until that moment, she had managed to keep calm.

They had revisited her failures with her five older children, all of whom had been apprehended. They had asked about her estranged, jailed father. They questioned the baby’s father, Merle, too.

Sarah told them she had a room ready for the baby. She pointed to the stuffed diaper bag she brought to the hospital. She knew drug tests would come back clean — she had pre-emptively tested herself at her doctor’s office. “I was thinking I could win, beat them to the battle,” she said.

Then they refused to let her breastfeed, and she started to heave with angry, despairing sobs.

They left and returned with apprehension papers, telling her she was too emotionally unstable to care for an infant.

She pleaded with the child protection workers to at least take the diaper bag. They wouldn’t. She carried the bag home with her that night, brought it up to the empty baby’s room, and wept.

Amy was taken to foster care and then to a respite home, where she died in a playpen on Sept. 23, 2011, two months after she was born. Sarah still doesn’t know why.

“We are spiritual people. Our belief is if a baby doesn’t feel wanted from birth, the Creator will take her home.

“I feel guilty because that’s my child. I wanted her. I just couldn’t have her.”

In October 2013, Sarah and Merle sued the province for $1 million.

At least 12 Alberta families have sued the government in connection with the death of a child in care since 1999.

The province refused to release details of the lawsuits, and whether any settlements had been paid out, but the Edmonton Journal and Calgary Herald found court records for eight of the 12 lawsuits; those show the claims total at least $8.7 million.

The lawsuits range from a $45,000 claim for a baby girl who died of untreated pneumonia, to a $2.55 million claim for a baby girl found in an infant carrier. The mother of two Edmonton boys sued for just over $1 million after the children were injected with morphine and smothered to death during an unsupervised, court-ordered visit with their mentally unstable father.

Four of the lawsuits involve babies and toddlers who were dropped, thrown or shaken.

Edmonton lawyer Robert P. Lee says the secrecy surrounding these lawsuits undermines government accountability, and that taxpayers have a right to know how often the government is sued and how much they pay out to the biological parents of children who die in its care.

“Lawsuits are about changing behaviour,” Lee said. “If the government got sued every time a child died in care, and it was public, and people found out who made mistakes and how bad those mistakes were, then I think there would be more motivation for the government to change their ways.”

Between 1999 and 2013, 145 children died in government care, a Journal-Herald investigation revealed.

Only 12 families have sued.

Lee said parents of children who die in foster care seldom sue because they are already disenfranchised and the death of a child compounds their powerlessness.

“They’re not sophisticated enough to launch a lawsuit, or capable emotionally or psychologically,” Lee said. “And then their child dies. … To go around and find a lawyer to sue the government — it’s just not within their ability.”

The RCMP investigated Amy’s death, no charges were laid. The government conducted no internal investigation and her death did not result in any recommendations for change. The four-page internal report related to her death says she died from a cardiac arrest, but Sarah and Merle were told she died from Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. They have been unable to see copies of the autopsy report or the hospital records. A fatality inquiry has been called, but not scheduled.

In their lawsuit, Sarah and Merle allege the province “carelessly apprehended Amy when she did not need to be apprehended,” and that officials have refused to give them any information about how she died.

“(Officials) are intentionally hiding the information,” the lawsuit reads.

Amy was buried on the Paul First Nation, where her parents were born and raised. In mid-November, Merle trudged through two feet of snow in a driving storm to visit his daughter’s grave. As the snow soaked into his jeans, he crouched to dust off a stuffed monkey holding a big red heart. Snow pelted his back. He said nothing.

He returned to the family’s simple, cozy home. Sarah walked out of the bedroom, carrying their new baby girl. Her chubby cheeks were pink and her hair was tousled after a nap. She just celebrated her first birthday.

The child was conceived after Amy died, and Sarah contemplated ending the pregnancy. “I didn’t think I could bear to have another child taken away from me,” she said. A friend persuaded her to keep the baby.

When she went to the hospital to give birth, she couldn’t bring herself to pack along a diaper bag.

But this time, she brought their daughter home.

Source: Edmonton Journal

Couple mourns foster son: ‘It was the worst day of our lives’

Foster parents, caseworkers devastated when child dies in their care — yet they often face brunt of blame

Several people in this story are referred to by first-name pseudonyms only to protect their identities.

EDMONTON - In the minutes after John realized his foster son was dead, time stopped.

People around him were running wild, sobbing. His heart seemed to disconnect from his mind. He couldn’t breathe.

His wife tried to rush to the boy’s side, and had to be held back.

“It was the worst day of our lives,” John said, his voice low and heavy with grief. “It felt like a bad dream. It still feels like a bad dream.”

We would like to tell you how this child died, how long the couple had loved and cared for him, and why they were so proud of him.

We would like to describe one heartbreaking moment at his funeral which illustrates the incomprehensibly complex emotional ties that bind a foster family to a boy and to his biological family.

We want to tell you about John and his wife and who they are, the remarkable reason they started fostering, and the sacrifices they have made to care for children who are not their own.

But we cannot.

If we did, Alberta government officials would be able to identify the case and the family could be sanctioned by the Ministry of Human Services for speaking to the media.

“We were in so much emotional pain at the time, because we felt guilty — should have done this, shouldn’t have done that, should have been more vigilant,” John said. “But I was as vigilant as I possibly could be.”

Between 1999 and 2013, 145 Alberta children died after they were apprehended from their families. Of those, 86 were in the care of kinship or foster parents when they died.

A FOSTER PARENT IS HARDER ON THEMSELVES THAN ANYONE ELSE

The death records were obtained by the Edmonton Journal and Calgary Herald after a four-year legal battle with the provincial government, which didn’t want to release details of the cases. Contained in those reports, which remained hidden until now, are astonishing stories about the lengths to which caseworkers and foster parents have gone to help babies, children and teens in crisis.

One foster parent stayed in hospital to cuddle a newborn baby who was given only days to live. Several others took sick children into their homes and cared for them, knowing all the while that death would soon come. Many others care for disabled and medically fragile children for years, and are credited with helping those children live longer, happier lives.

Still others, like Jane, take in profoundly troubled children, love them, raise them and then send them out into the world, only to pick up the phone one day and hear the child has committed suicide.

Jane, a veteran foster parent, says the death of a child in foster care sends shock waves through the entire fostering community.

“A foster parent is harder on themselves than the department, the law or anybody else will be,” Jane said. “You will second-guess yourself. Did I do the right thing? What else could I have done?”

After a child dies, foster parents suddenly find themselves at the centre of a maelstrom. The caseworker might be barred from talking to them, they might have to get a lawyer, and their home comes under intense scrutiny from police and child welfare officials. There can be lawsuits or criminal charges.

The grief of losing one child is compounded by the fear that the ministry will take away the remaining children in their home, including their biological children. The deceased child’s biological parents — and the public — can be quick to judge.

“When you’re a foster parent, you’re guilty until you prove yourself innocent. Period,” Jane said. “Whereas guys that go into jail, they’re innocent until proven guilty. Why is it backward?”

RARE FOR FOSTER PARENTS TO FACE CHARGES

Katherine Jones, executive director of the Alberta Foster Parent Association, said losing a foster child is always traumatic.

“They take this child in because of their love and their care for humanity,” she said. “When a child does die, it affects their whole family. It’s like their own loss; it’s tragic. It’s not only them who are affected, it’s the children — the other children in their home, their biological families, their neighbours, their friends, the foster care community. We are all saddened by those tragedies.”

In rare cases, foster parents do face criminal charges after a child dies in their care. Since 1999, five foster and kinship parents have been charged in connection with the death of a child in their care.

All of the deaths involved allegations of shaking or throwing a child under four; all of the foster parents were initially charged with second-degree murder.

Three pleaded guilty to manslaughter, and received sentences ranging from two to seven years.

In the fourth case, foster mother Lily Choy has twice been convicted of manslaughter after a toddler in her care suffered a traumatic head injury in 2007. She has been sentenced to eight years in prison, but maintains her innocence and continues to appeal.

The most recent case, involving Morinville foster mother Christine Laverdier, is connected to the 2010 death of a 21-month-old girl. It is slated to go before a jury in January next year.

DEATHS SHAKE FRONT-LINE WORKERS TO THE CORE

Front-line caseworkers also suffer when a child dies on their caseload.

Pat, an Alberta social worker who spoke on condition of anonymity, said any death shakes front-line workers to the core.

“We are charged with keeping kids safe, and when we’re unable to — to the point where a child dies — it just highlights everything: the powerlessness, the inability to keep kids safe, it just goes to the core of who we are as people, our practices, our ethics, it just calls all of that into question.”

“It never goes away.”

Pat risked everything to tell us the caseworkers’ side of the story; they, too, are barred from speaking publicly about their experience.

“Being defensive isn’t the answer,” Pat said. “Learning from the (death) should be the province’s goal. To honour the child that has died, the least we can do is improve the system.”

Many experts say that will only happen when better training and support is provided for caseworkers, who struggle with heavy caseloads in very stressful situations.

“Given the extraordinary lack of preparation and support for people in this field of work, it is amazing there aren’t more deaths,” said Allan Wade, who trains child protection workers around the world. “It is amazing that people manage to do the quality of work they do with the scant resources they get.”