Americans use the Internet to abandon children adopted from overseas

Part 1: When a Liberian girl proves too much for her parents, they advertise her online and give her to a couple they’ve never met. Days later, she goes missing.

KIEL, Wisconsin – Todd and Melissa Puchalla struggled for more than two years to raise Quita, the troubled teenager they'd adopted from Liberia. When they decided to give her up, they found new parents to take her in less than two days – by posting an ad on the Internet.

Nicole and Calvin Eason, an Illinois couple in their 30s, saw the ad and a picture of the smiling 16-year-old. They were eager to take Quita, even though the ad warned that she had been diagnosed with severe health and behavioral problems. In emails, Nicole Eason assured Melissa Puchalla that she could handle the girl.

"People that are around me think I am awesome with kids," Eason wrote.

A few weeks later, on Oct. 4, 2008, the Puchallas drove six hours from their Wisconsin home to Westville, Illinois. The handoff took place at the Country Aire Mobile Home Park, where the Easons lived in a trailer.

No attorneys or child welfare officials came with them. The Puchallas simply signed a notarized statement declaring these virtual strangers to be Quita's guardians. The visit lasted just a few hours. It was the first and the last time the couples would meet.

To Melissa Puchalla, the Easons "seemed wonderful." Had she vetted them more closely, she might have discovered what Reuters would learn:

- Child welfare authorities had taken away both of Nicole Eason's biological children years earlier. After a sheriff's deputy helped remove the Easons' second child, a newborn baby boy, the deputy wrote in his report that the "parents have severe psychiatric problems as well with violent tendencies."

- The Easons each had been accused by children they were babysitting of sexual abuse, police reports show. They say they did nothing wrong, and neither was charged.

- The only official document attesting to their parenting skills – one purportedly drafted by a social worker who had inspected the Easons' home – was fake, created by the Easons themselves.

On Quita's first night with the Easons, her new guardians told her to join them in their bed, Quita says today. Nicole slept naked, she says.

Within a few days, the Easons stopped responding to Melissa Puchalla's attempts to check on Quita, Puchalla says. When she called the school that Quita was supposed to attend, an administrator told Puchalla that the teenager had never shown up.

Quita wasn't at the trailer park, either. The Easons had packed up their purple Chevy truck and driven off with her, leaving behind a pile of trash, a pair of blue mattresses and two puppies chained in their yard, authorities later found.

The Puchallas had rescued Quita from an orphanage in Liberia, brought her to America and then signed her over to a couple they barely knew. Days later, they had no idea what had become of her.

When she arrived in the United States, Quita says, she "was happy … coming to a nicer place, a safer place. It didn't turn out that way," she says today. "It turned into a nightmare."

The teenager had been tossed into America's underground market for adopted children, a loose Internet network where desperate parents seek new homes for kids they regret adopting. Like Quita, now 21, these children are often the casualties of international adoptions gone sour.

Through Yahoo and Facebook groups, parents and others advertise the unwanted children and then pass them to strangers with little or no government scrutiny, sometimes illegally, a Reuters investigation has found. It is a largely lawless marketplace. Often, the children are treated as chattel, and the needs of parents are put ahead of the welfare of the orphans they brought to America.

The practice is called "private re-homing," a term typically used by owners seeking new homes for their pets. Based on solicitations posted on one of eight similar online bulletin boards, the parallels are striking.

"Born in October of 2000 – this handsome boy, 'Rick' was placed from India a year ago and is obedient and eager to please," one ad for a child read.

A woman who said she is from Nebraska offered an 11-year-old boy she had adopted from Guatemala. "I am totally ashamed to say it but we do truly hate this boy!" she wrote in a July 2012 post.

Another parent advertised a child days after bringing her to America. "We adopted an 8-year-old girl from China… Unfortunately, We are now struggling having been home for 5 days." The parent asked that others share the ad "with anyone you think may be interested."

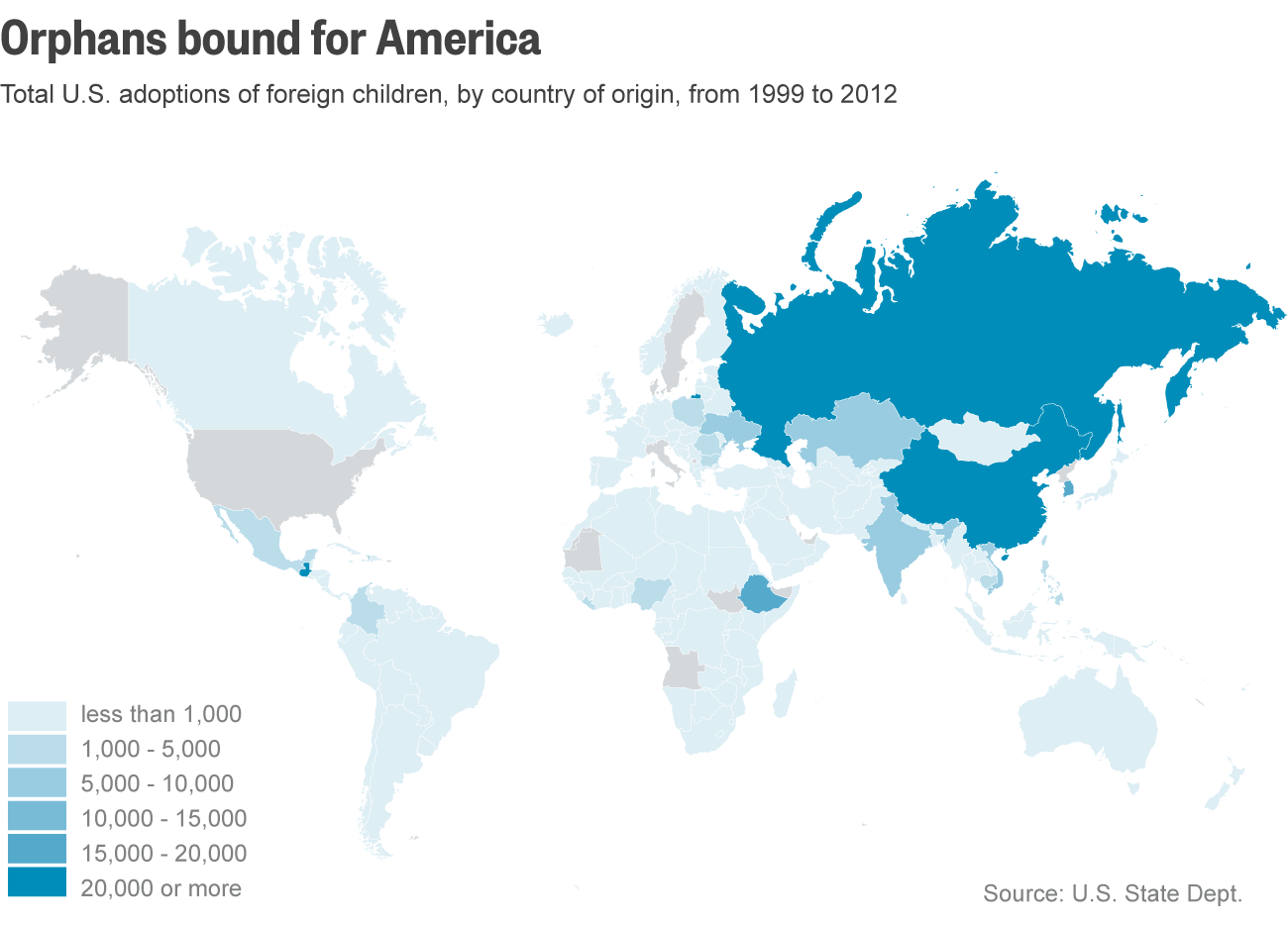

Reuters analyzed 5,029 posts from a five-year period on one Internet message board, a Yahoo group. On average, a child was advertised for re-homing there once a week. Most of the children ranged in age from 6 to 14 and had been adopted from abroad – from countries such as Russia and China, Ethiopia and Ukraine. The youngest was 10 months old.

After learning what Reuters found, Yahoo acted swiftly. Within hours, it began shutting down Adopting-from-Disruption, the six-year-old bulletin board. A spokeswoman said the activity in the group violated the company's terms-of-service agreement. The company subsequently took down five other groups that Reuters brought to its attention.

A similar forum on Facebook, Way Stations of Love, remains active. A Facebook spokeswoman says the page shows "that the Internet is a reflection of society, and people are using it for all kinds of communications and to tackle all sorts of problems, including very complicated issues such as this one."

The Reuters investigation found that some children who were adopted and later re-homed have endured severe abuse. Speaking publicly about her experience for the first time, one girl adopted from China and later sent to a second home said she was made to dig her own grave. Another re-homed child, a Russian girl, recounted how a boy in one house urinated on her after the two had sex; she was 13 at the time and was re-homed three times in six months.

"This is a group of children who are not being raised by biological parents, who have been relocated from a foreign country" and who sometimes don't even speak English, says Michael Seto, an expert on the sexual abuse of children at the Royal Ottawa Health Care Group in Canada. "You're talking about a population that appears to be especially vulnerable to exploitation."

Giving away a child in America can be surprisingly easy. Legal adoptions must be handled through the courts, and prospective parents must be vetted. But there are ways around such oversight. Children can be sent to new families quickly through a basic "power of attorney" document – a notarized statement declaring the child to be in the care of another adult.

In many cases, this flexibility is good for the child. It allows parents experiencing hard times to send their kids to stay with a trusted relative, for instance. But with the rise of the Internet, parents are increasingly able to find complete strangers willing to take in unwanted children. By obtaining a power of attorney, the new guardians are able to enroll a child in school or secure government benefits – actions that can effectively mask changes of custody that take place illegally outside the purview of child welfare authorities.

There is one potential safeguard: an agreement among the 50 U.S. states, the District of Columbia and the U.S. Virgin Islands called the Interstate Compact on the Placement of Children, or ICPC. The agreement requires that if a child is to be transferred outside of the family to a new home in a different state, parents notify authorities in both states. That way, prospective parents can be vetted.

The compact has been adopted by every state and is codified in various statutes that give it the force of law. Even so, these laws are seldom enforced, in part because the compact remains largely unknown to law enforcement authorities. Each state is also left to decide how to punish those who give or take children in violations of the compact's provisions. Some states attach criminal sanctions – generally, misdemeanors. Other states aren't explicit about how violations should be handled.

A child might be removed from the new home if an illegal re-homing is discovered. But seldom is either set of parents punished. No state, federal or international laws even acknowledge the existence of re-homing.

International adoptees are especially susceptible to being re-homed. At least 70 percent of the children offered on the Yahoo bulletin board, Adopting-from-Disruption, were advertised as foreign-born.

Americans have adopted about 243,000 children from other countries since the late 1990s. But unlike parents who take in American-born children through the U.S. foster-care system, many adults adopting from overseas receive little or no training. It isn't unusual for the children they bring home to have undisclosed physical, emotional or behavioral problems.

No authority tracks what happens after a child is brought to America, so no one knows how often international adoptions fail. The U.S. government estimates that domestic adoptions fail at a rate ranging from "about 10 to 25 percent." If international adoptions fail with about the same frequency, then more than 24,000 foreign adoptees are no longer with the parents who brought them to the United States. Some experts say the percentage could be higher given the lack of support for those parents.

A U.S. federal law, passed in 2000, requires states to document cases in which they take custody of children from failed international adoptions. The State Department then collects that information. In addition, adoption agencies are supposed to report to the department certain types of failed international adoptions that come to their attention.

But many states say they are unable to keep track of the cases because their computer systems are antiquated. And the State Department won't disclose the number of failed international adoptions that are reported by adoption agencies.

"Because the State Department is not the authoritative source of information regarding dissolutions and is not always notified when adoptions are dissolved, we do not provide statistics," a State Department official said.

The failure to keep track of what happens after children are brought to America troubles some foreign governments. So do instances of neglect or abuse that become known. Often cited is the case of the Tennessee woman who returned a 7-year-old boy she adopted from a Russian orphanage. The woman had cared for him only six months when she put the boy on a flight to Moscow in April 2010. He was accompanied by a typed letter that read in part, "I no longer wish to parent this child."

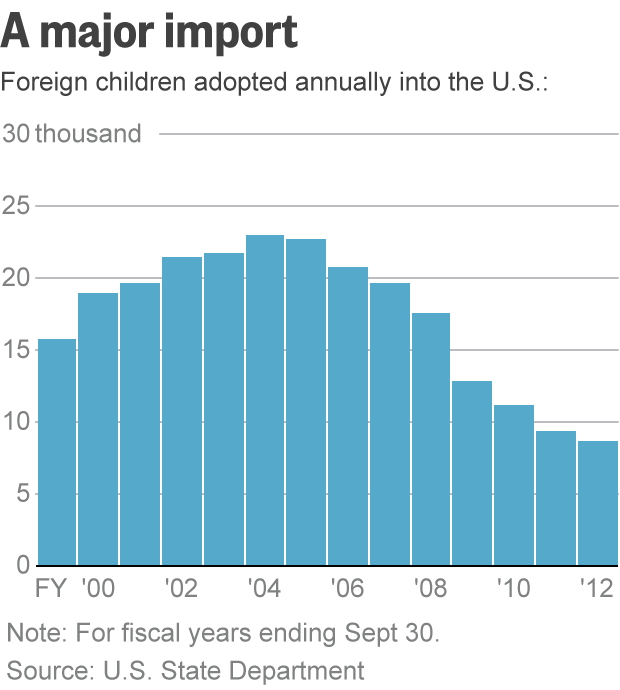

Late last year, Russia banned adoptions by Americans amid a broader diplomatic dispute. Other nations, including Guatemala and China, have also made the process more difficult. As a result, the number of foreign-born children adopted into the United States has declined from a peak of almost 23,000 in 2004 to fewer than 10,000 a year today.

The recent obstacles to bringing new kids to America could make the Internet child exchange even more appealing. A participant in one online bulletin board characterized the re-homing groups as "the 'latest country' to adopt from."

Other participants wrote about openly defying government efforts, foreign and domestic, to keep track of children from failed adoptions (also sometimes called "disrupted" adoptions).

"We adopted two children from Russia. We have disrupted our daughter. What business of the Russian government?" one parent wrote in July 2012. "We never let anyone know about the disruption." (Russia is among the nations that seek periodic updates on children adopted from there.)

Parents who offer their children on the Internet say they have limited options. Residential treatment centers can be expensive, and some parents say social services won't help them; if they do contact authorities, they fear being investigated for abuse or neglect.

The problems – and the isolation parents feel – can prove overwhelming. On the bulletin boards, parents talk of children becoming abusive and violent, terrorizing them and other kids in the household.

"People get in over their heads," says Tim Stowell, an adoptive parent who created the Facebook group last year. "The main thing is to offer hope for families that have no hope... I also knew there were people looking to adopt kids from those situations, so I wanted to get those people together, kind of like a clearinghouse."

Not until January 2011 did any official responsible for overseeing the U.S. child-protection compact call attention to the dangers of the online network. In a nationwide alert to state child welfare authorities, an administrator for the ICPC warned that adoptive parents were sending children to live with people they met on the Internet. The practice, the official wrote, is "placing children in grave danger."

The official who sent the memo, Stephen Pennypacker, says he issued the warning after a child welfare worker in one state noticed cases of kids being sent to new parents without the approval of authorities.

In the alert, Pennypacker asked that such cases be documented and reported to the national non-profit organization that oversees the ICPC. He says he also told child protection officials in each state to alert their attorneys general, local police and social workers "so that people could be on the lookout."

Despite the urgency of the request, Pennypacker says there has been no response.

As part of its investigation, Reuters reviewed thousands of pages of records – many of them confidential – from court cases, police reports and child welfare agencies. Reporters examined ads for children and emails between parents, and also identified eight Internet groups in which members discussed, facilitated or engaged in re-homing. Reporters then analyzed thousands of posts from the group that Yahoo subsequently shut down, Adopting-from-Disruption.

Some participants in that group both offered and sought children for re-homing, sometimes simultaneously. Others looked to offload more than one child at a time. Some sought new parents for children who already had been re-homed. A 10-year-old boy from the Philippines and a 13-year-old boy from Brazil each were advertised three times. So was a girl from Haiti. She was offered for re-homing when she was 14, 15 and 16 years old.

In an interview earlier this year, Nicole Eason - the woman who disappeared with Quita - referred to private re-homing as "non-legalized adoption."

"The meaning of non-legalized is, 'Hey, can I have your baby?'" Eason said.

She discussed why she was so motivated to be a mother. "It makes me feel important," she said.

And she described her parenting style this way: "Dude, just be a little mean, OK? … I'll threaten to throw a knife at your ass, I will. I'll chase you with a hose.

"I won't leave burns on you. I won't leave marks on you. I'm not going to send you with bruises to school," she said. "Make sure you got three meals a day, make sure you have a place to live, OK? If you need medication for your psychological problems, I've got you there. You need therapy? You need a hug? You need a kiss? Somebody to tickle with you? I got you. OK? But this world is not meant to be perfect. And I just don't understand why people think it is."

The story of the Easons and the girls and boys they have taken through re-homing illustrates the many ways in which the U.S. government fails to protect children of adoptions gone awry. It shows how virtually anyone determined to get a child can do so with ease, and how children brought to America can be abruptly discarded and recycled.

A CHILD FOR FREE

The night before leaving Quita with the Easons, Melissa Puchalla showed her daughter a picture of the couple. Like Quita, Calvin Eason is black. Nicole is white, and Puchalla thought Quita might thrive in a mixed-race household.

The Puchallas also say they were giving up the teenager to protect their other children. Quita was unpredictable and violent, Melissa says, and her siblings had grown frightened of her. "There was no other option," Melissa says today.

Puchalla assured her daughter that the Easons were "very good people," Quita remembers. "But I was like judging in my mind: 'How do you know?'" Quita says today. She says she spent the night crying.

The Easons were elated. They were about to get a child, for free.

Part of the allure of re-homing is that the process is far cheaper than formal adoptions. Adopting from a foreign country can cost tens of thousands of dollars. Taking custody through re-homing often costs nothing. In fact, taking a child may enable the new family to claim a tax deduction and draw government benefits. The Easons view re-homing as a way around a prying government, and a way to take a child inexpensively.

"If you don't want to pay $35,000 for a kid," Nicole Eason says today, "you take your chances."

For Quita, the drive to the Eason place was a blur. But she remembers vividly when her adoptive father, Todd Puchalla, stopped in front of a mobile home with an overgrown lawn. Some of the trailers were well-maintained. This one, Quita thought, looked like a junkyard.

From the picture her mother had shown her, Quita recognized the Easons immediately. Both were large, well over 200 pounds, and Calvin was tall – about 6-foot-2. But what first caught the Puchallas' attention was the tube coming out of Calvin's neck a few inches beneath his chin. It was from a tracheostomy, a surgical procedure to alleviate a sleep disorder.

"We were a little standoffish about him because he has a trach," Melissa Puchalla recalls. "But they were warm, and they were caring. They seemed kind."

Today, Melissa Puchalla says, "Maybe a red light should've went off – too good to be true. But at that point, I was walking in such a fog."

Not only were the Easons willing to take Quita, but they would gladly do so through the simple device of a power of attorney document, about 400 words long. The paper is signed by the old parents and the new guardians, and witnessed by a notary. As happened in Quita's case, no lawyers or government authorities are involved. The document is filed nowhere; it functions, in essence, as a receipt. Such agreements fail to satisfy the ICPC when custody of the child is exchanged across state lines and authorities in both states aren't involved. But that hasn't stopped some parents from handling transfers this way.

Not long after the Puchallas arrived with Quita, the Easons presented a cake. "Welcome home Quita" was written in orange frosting.

Nicole also had a card for Melissa. Inside were printed these words: "I have faith that you're going to come out of this experience with more wisdom and resilience than you ever thought possible."

Melissa helped Quita unpack and hugged her goodbye. Everything would be fine, Melissa assured her. Melissa also devised a code: Quita would say "I love asparagus" over the phone if she felt in danger. (Quita didn't use the code, Melissa says.)

As the Puchallas drove away, Melissa sobbed. She calls the decision "the hardest thing we've ever done in our lives." Quita still can't reconcile it. "How would you give me up when you brought me to be yours?" she asks.

In the days that followed, two puppies scampered through the trailer, gifts from the Easons to Quita. The dogs lifted the teenager's spirits, but they weren't housebroken and no one cleaned up after them. No one did the dishes, either, or the laundry.

More troubling, Quita says, was that the Easons took her into their bed: "They call me in there to sleep … to lay in the bed with them." In bed, "Nicole used to be naked and stuff. It was not right to me."

The sleeping arrangements Quita describes are consistent with the experience of another child the Easons took in. Nicole and Calvin both say that no child they took in ever slept in their bed.

A MISSING CHILD

Within days, the Easons had stopped answering Melissa Puchalla's calls or returning her emails, Puchalla says. They attached a makeshift camper to the truck bed of their purple Chevy S-10, packed most of their belongings and left the state. Riding along was a friend of the Easons, a man on parole in Illinois for armed robbery.

When Melissa Puchalla called the school Quita was supposed to attend, she talked with an administrator who then contacted state child protection officials. Although Puchalla had signed over custody of Quita, she says she felt obligated to ensure Quita was safe.

Authorities, including police, subsequently went to the mobile home park in Westville. A neighbor told a child welfare official that before the Easons left, Quita had told the neighbor's daughter that the Easons would be heading to upstate New York to visit Nicole's mother.

The puppies, left chained in the yard, were retrieved by animal protection officers.

As authorities searched for Quita, they discovered information that could have precluded the Easons from taking custody of the teenager, if the proper officials had been involved, adoption experts say.

Illinois authorities determined that the Easons had fabricated a document they provided to the Puchallas called a "home study." It purported to be from a social worker who had visited their home and done background checks of the couple. Actually, Nicole had found a sample document on the Internet and filled it out herself. Some of the information was true; the rest was fiction.

"Quita Puchalla is missing as is the Eason family," reads a confidential report by the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services. The internal report was dated Oct. 20, 2008, 16 days after the Puchallas had dropped Quita at the Easons.

"The Easons faked their home study," the report says. "The Easons are suspected of using the disrupted adoptions of out of country children… Because there are other states involved, licensing issues and possible public aid fraud as well as a missing child, this matter may involve the FBI at some point."

Illinois officials did share their findings with the local sheriff's office and with the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Authorities then contacted the New York State Police, who located the Easons' truck in Stephentown, New York. It was parked outside a house where Nicole's mother lived.

When police went to the home on Oct. 21, they found Nicole, Calvin and Quita. The man convicted of armed robbery who had traveled with the Easons to New York wasn't there.

Later that day, investigators separately interviewed the Easons and Quita. Reports show that the teenager said the Easons had pornography in their house. Police took Quita to a homeless shelter; the next day, she was put on a bus. She was heading back to Wisconsin, by herself, to the parents who had given her up not three weeks before.

Taking Quita from the Easons and returning her to the Puchallas was the extent of the response by authorities.

New York State Police concluded that the Easons had committed no crimes in their jurisdiction. Illinois authorities took no legal action, and neither did officials in Wisconsin. No one did anything to prevent the Easons from taking a child again.

Hundreds of other adoptive parents were seeking new homes for their unwanted children through Internet message boards like those that had featured Quita. Nicole Eason knew how the child exchange worked. She would tap it again after losing Quita, much as she had used it before.

One of the first times, Eason had gone by the screen name Big Momma. The custody transfer took place in a hotel parking lot just off the highway, and the man who went with her to get the 10-year-old boy would later be sentenced to federal prison. His crime: trading child pornography.

Source: Reuters

In a shadowy online network, a pedophile takes home a ‘fun boy’

Part 2: A self-proclaimed ‘lil boylover’ and a woman accused of neglect find a child on the Internet – and pick him up hours later in a hotel parking lot.

EDITOR'S NOTE: This story contains language that some readers may find offensive.

APPLETON, Wisconsin – Online, she called herself Big Momma; he went by the name lovethemcute. And in the summer of 2006, housemates Nicole Eason and Randy Winslow were surfing the Internet with a common objective.

Each was looking for children.

Winslow – lovethemcute – was 41, balding and paunchy. He swapped pictures of naked children and would later spend time in a chat room called baby&toddlerlove, where he described himself as a "lil boylover," court documents show. There, he would graphically boast of molesting boys and explain how to keep the abuse quiet: "Just have to raise them to think its fine and not to tell anyone," he wrote in a chat with an undercover federal agent. "What is done in the family stays in the family."

Eason – Big Momma – was about to turn 28. She had moved to Illinois from two states where authorities had taken away her biological children years earlier. In one report, authorities noted that a child she and friends were watching had died in her care.

Living away from her husband, Calvin, and with Winslow in the Illinois town of Tilton, Eason wanted to be a mother again. A few hours on an Internet bulletin board were all she would need to find a new child.

On July 14, 2006, Eason connected online with Glenna Mueller, a Wisconsin mother ready to give up a 10-year-old boy she had adopted. Mueller, 46, was once a licensed daycare provider. Struggling in a second marriage, she largely supported herself by collecting government subsidies for the seven children she adopted. She had taken the 10-year-old about three years earlier. Now, his tantrums were too much, Mueller told Eason.

"I couldn't stand to look at him anymore," Mueller says today. "I wanted this child gone."

That's when Mueller turned to ConsideringDisruptinganAdoption, a Yahoo group for parents struggling to raise the children they adopted. (After Reuters asked Yahoo about the group, which has been active for nine years, the company shut it down for violating Yahoo's terms of service.) Most of the children mentioned on such bulletin boards come from overseas. Mueller's son – an African-American boy – had been adopted out of the U.S. foster care system. On the site, she posted a description of the boy and her contact information. Almost immediately, Eason reached out.

Early that July morning, the two began exchanging emails, and Mueller sent Eason a picture of the boy. "He is ADORABLE!!!!!!!!!!!" Eason replied minutes later. She quickly added: "Randy wants to know if u would like a visit today?"

By that afternoon, Eason and Winslow were heading north, driving five hours from Illinois to Appleton, Wisconsin, where Mueller lived. They met in a hotel parking lot just off the highway, and Mueller brought the boy.

In an email, Eason had told Mueller that they need not involve a lawyer. No child welfare officials were notified, either. Along with the boy's birth certificate, Mueller handed Nicole a note: Eason and Winslow had her permission to care for her son.

Mueller knew little about the couple. She wasn't certain where or if Eason or Winslow worked, or if they were married; she knew nothing about Eason's two biological children having been taken away, or of Winslow's affinity for young boys; she wasn't even sure of their address. She did know they were willing to take a child she could no longer stomach, and that was enough.

"I was desperate and sick to death of it," Mueller says of caring for the 10-year-old, whose name is withheld because Reuters could not reach him. "And I'm like, 'You know what? Take him for a visit. Let me know.'"

After less than an hour outside the Fairfield Inn, Eason and Winslow drove off with a young boy, a commodity in America's underground market for discarded adopted children.

As nations around the world make adopting overseas more difficult for Americans, the U.S. government has taken no measures to restrict informal "private re-homings," custody transfers of unwanted children that often start in online bulletin boards, a Reuters investigation has found.

The unregulated nature of this market makes it especially dangerous. Because the government doesn't oversee the bulletin boards, people like Randy Winslow can easily gain custody of a child, without authorities ever knowing. Scrutinizing those who want children is often left to parents who are eager to get rid of the kids.

"I would have given her away to a serial killer, I was so desperate," one mother wrote in a March 2012 post about re-homing her 12-year-old daughter.

"There's hundreds of people looking for new homes for kids," Mueller says of those who use the online bulletin boards. One participant referred to the re-homing forums as "'farms' in which to select children."

Many of the online posts say the unwanted children have physical or mental disabilities. In the group Reuters analyzed, more than half were described as having some sort of special need. About 18 percent were said to have a history that included sexual or physical abuse.

Such descriptions could serve as a beacon for predators. "If you advertise details of things like their substance abuse or sexually acting out, that's waving a red flag," says Michael Seto, an expert on the sexual abuse of children at the Royal Ottawa Health Care Group in Canada.

Especially at risk are children described as troubled and lacking a consistent parental figure, says Eric Ostrov, a Chicago-based forensic psychologist who evaluates sex offenders. Those depictions, Ostrov says, would be a "tremendous lure."

The great majority of children on the bulletin boards fit that profile. Most were adopted from overseas and brought to America. But children born in the United States can end up in the underground child exchange, too. The case of the 10-year-old taken by Eason and Winslow illustrates how easily parents will turn children over to strangers met online.

"Nowadays, people are searching out other people," Nicole Eason said in an interview. "That way, nobody's judging nobody."

NICOLE'S DAUGHTER

In early 2000, six years before picking up Glenna Mueller's son in the hotel parking lot, Nicole Eason came to the attention of child welfare authorities in Massachusetts.

Eason, then 21, had taken her biological baby daughter to a hospital in the city of Pittsfield. Doctors at Berkshire Medical Center determined that the girl, 9 months old, had a broken femur "for which the parents had no explanation," court records show. "A full skeletal X-ray" was done, and "two old fractures were discovered that were in different stages of healing," according to court records. "The parents had never sought medical attention for those fractures."

Rebecca Kickery, a former friend of Nicole's, says she remembers the incident that put the girl in the hospital. She says she told a child welfare worker what she witnessed.

The baby was "chasing her mom in the walker," Kickery says, and Nicole Eason "was cussing at her. She grabbed the tray of the walker and yanked her... When she yanked her, her daughter's leg went one way and her body went the other, and I heard it cracking like you crack a stick. And I just thought, this poor little girl."

In an interview with Reuters, Nicole Eason said no such incident took place.

A report by Massachusetts officials, dated Jan. 3, 2000, documents the baby's injuries. Subsequent court records show that "the child was removed from the parents at that time." Officials cited "neglect."

A month later, on Feb. 5, 2000, Nicole and Calvin Eason were at Kickery's Pittsfield apartment with friends. Kickery had asked her sister to watch her 18-month-old son, Austin.

That afternoon, Nicole later told police, the group was playing cards while Austin and his young cousin took a bath. Nicole said she heard a child crying in the bathroom and "thought that the water might have been cold because God knows how long they were in there."

Nicole went to the bathroom and saw Austin lying face down in the water, the police report says. She alerted Kickery's sister and left the bathroom without trying to pull the boy out. "I just freaked out," Nicole told police.

The report, dated Feb. 14, 2000, indicates that Nicole Eason was the last person to check on the children and the first adult to spot Austin face down in the water.

The child couldn't be revived, and the drowning was ruled an accident. Within days, police determined that there was "no reason to expect foul play but rather this appears to be a case of negligence." No charges were filed; under Massachusetts law, prosecutors must show that a caregiver's actions "went beyond mere negligence and amounted to recklessness," according to jury instructions offered in the state.

Today, Kickery wants authorities to reopen the investigation, but a spokesman with the Berkshire District Attorney's Office says that, absent any new evidence, the case is closed. Nicole Eason says she had nothing to do with the baby's death.

LEAVING MASSACHUSETTS

By 2002, Calvin Eason and a pregnant Nicole had moved to South Carolina. That March, Nicole gave birth to a boy.

Massachusetts child protection officials learned of the move and told South Carolina authorities about the Easons' history. They explained that Nicole's daughter was already in the foster care system. "The allegations," a report by South Carolina authorities recounted, "are abuse and neglect." (The couple's parental rights to the girl were subsequently terminated.)

Although the Kickery boy's death had been ruled an accident, Massachusetts authorities also brought Nicole's involvement in the matter to the attention of South Carolina officials. An incident report, dated Feb. 28, 2002 and prepared by the Dorchester County Sheriff's Office in South Carolina, notes that a "child died in Subject's care."

About a week after Nicole's son was born, the state executed an emergency removal of the newborn from the Eason home in Summerville, South Carolina, sheriff's records show. Authorities cited the neglect investigation of the Easons in Massachusetts and the conditions in the couple's South Carolina home.

"The home environment was deplorable for an infant, trash, clothes, stale food and stagnant water," according to a March 27, 2002, report by the sheriff's office. "The parents have an open investigation in (Massachusetts) where their parental rights are being terminated due to physical abuse on another child. Parents have severe psychiatric problems as well with violent tendencies."

In interviews earlier this year at a house they were renting in Tucson, Arizona, the Easons said that both children were still living with them. No pictures of any child hung on the walls, but there were a half-dozen plaques with adages about parenting. One read, "Daughters hold our hands for a little while but hold our hearts forever."

Nicole said South Carolina officials briefly removed their biological son years ago after someone reported that she had killed the boy and stuffed him into a tote bag. But he was returned to them within a few days, she said, after officials determined she had done nothing wrong.

In truth, the Easons never got the children back. The boy was adopted out of foster care, a South Carolina child welfare official said. The girl has either been adopted or remains in foster care; a Massachusetts official would not say which.

Asked last month to explain why officials in two states reported that her children had been permanently removed, Nicole said someone was lying. "I haven't had problems with social services," she said. "That's what I'm claiming."

THE BABYSITTER

Her biological children gone, Nicole Eason babysat for other parents.

A neighbor in North Charleston reported to police in 2003 that she suspected Nicole had molested the neighbor's young daughter. The girl, who was 4 or 5, told her mother that Nicole had been showering and sleeping naked with the child, the mother told police. When authorities interviewed the girl, she "had not disclosed any pertinent information for criminal charges," according to a report by the North Charleston police, dated Feb. 27, 2003.

As police investigated the allegations, Nicole was being treated in the psychiatric ward of The Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston for "an unrelated incident," according to the police report.

No charges were filed, but the mother secured a protective order against Eason when Eason left the hospital weeks later. Nicole says she never abused the girl.

In 2005, another allegation surfaced, this time against Calvin Eason.

A young boy who suffered from mental illness told his counselor that Calvin had touched him improperly while bathing the boy. The boy's mother didn't believe the allegation, according to a report by North Charleston police, and no charges were brought. The boy's mother couldn't be reached for comment.

When Reuters first visited the Easons, Calvin wore a sleeveless maroon T-shirt with the words GOOD DADS MAKE A DIFFERENCE. He said he never improperly touched the boy he had babysat, and added: "I've got kids of my own I could already do that to. So why would I even try to do that to another child?"

The Easons bounced between jobs. By the summer of 2006, Nicole moved from South Carolina to Tilton, Illinois. Calvin says she relocated for a job and he stayed behind.

Nicole lived with her friends Randy Winslow and Winslow's brother, according to Calvin. Later, Calvin joined her in the area, and the Easons moved to a different house.

Before Calvin arrived, Nicole had gone online and taken a child through the re-homing network.

'I CAN HANDLE HIM'

In July 2006, Nicole's pursuit of Glenna Mueller's adopted son was accomplished in a single day.

Ten years old, the boy had come out of the Wisconsin foster system small and underweight. He loved babies and animals but suffered emotional and behavioral problems, Mueller says. He would act out, attack other children and show no remorse, she recalls.

A stay-at-home mother in the paper-mill city of Appleton, Mueller was, in essence, a professional parent. Her income came from government assistance for her adopted sons and daughters. She says a Wisconsin child welfare officer told her that if she relinquished the 10-year-old to the state, the move might prompt an investigation that could result in her losing her other children.

Increasingly stressed, she turned to another Yahoo group, called ConsideringDisruptinganAdoption, to find the boy a new home. If she handled the matter privately, she reasoned, the state wouldn't have to know and therefore wouldn't investigate her for neglect or abuse.

Begun in 2004, the Yahoo group was an active online forum for adoptive parents seeking to re-home unwanted children. Mueller posted a description of the boy and asked if anyone was interested.

Nicole Eason responded by email: "OMG Glenna I CAN HANDLE HIM … I HAVE the love, patience and time…"

Mueller was eager to move forward but told Eason she couldn't afford an attorney.

They wouldn't need one, Eason assured her. She sent Mueller pictures of children she described as being "all part of my family" – including a daughter and stepson "from a previous marriage" and another boy and girl whom she described as Randy Winslow's niece and nephew.

Mueller responded by sending Eason additional pictures of the 10-year-old boy. Minutes later, Eason suggested they meet in person. She and Randy, she told Mueller, were willing to drive to Wisconsin that very day. Mueller agreed.

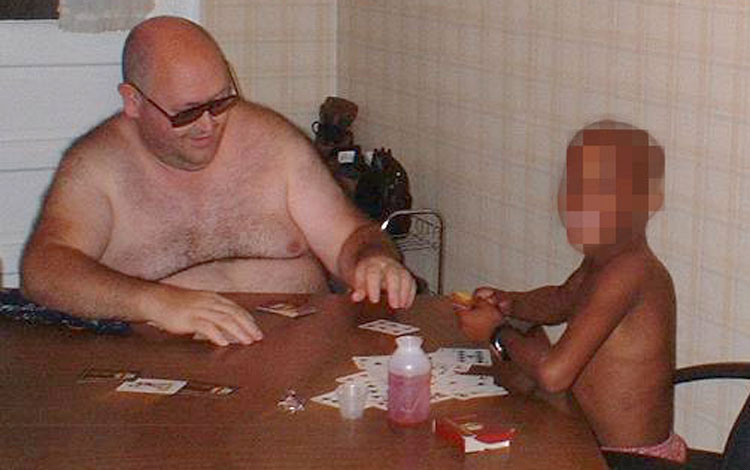

That afternoon, in the hotel parking lot off U.S. Highway 41, Mueller met Eason and Winslow for the first and only time.

Before the couple drove off with the boy, Mueller took a picture of the new family. The snapshot shows a small, lean child between the smiling pair. Winslow, wearing sunglasses, has his arm around the boy.

"I was a little concerned about Randy," Mueller recalls today. "He never said anything. He spent time with (the boy) and played with him but didn't interact with me.... But as long as they were on the up-and-up I was OK with them taking him. It was like, get him out of here.

"In hindsight, it was all wrong. I shouldn't have done it that way," she says. "But I did, you know."

THE STAY

Several months passed before the boy's caseworker in Wisconsin learned that Mueller had given the child to a couple in Illinois. Mueller says the caseworker insisted she take the the boy back. He told her that the transfer violated a legal requirement that authorities be notified when custody is transferred across state lines.

The caseworker "said I could be arrested," Mueller says. "It scared the bejesus out of me."

Mueller called Nicole Eason, who promised to meet her at the state line to give her the boy back. But on the day they arranged to meet, Mueller says, Eason didn't show. Today, Mueller says she cannot remember how the boy got back to her Appleton home. But she says neither Wisconsin nor Illinois authorities took action against her, Eason or Winslow for transferring custody illegally.

When the boy returned to Wisconsin in late 2006, he mentioned that he spent most of his time with Winslow, not with Nicole. "She left," he told Mueller. "I was there with Randy," Mueller recalls him saying.

As Mueller began searching online for another family to take him, Eason and Winslow also were back online, again looking for children.

While Eason worked the re-homing bulletin boards, Winslow spent time in a chat room called baby&toddlerlove. That's where an undercover federal agent named Kevin Laws found him in April 2007.

Laws, who works in the child exploitation investigative unit at the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, posed as a single grandfather living in Alaska. He told Winslow he was caring for his two grandchildren, kids he said he would let Winslow molest.

In his messages to Laws, court records show, Winslow shared child pornography and claimed to have experience "sucking boys" who were 7, 9 and 11 years old.

"Its all fun man no matter their age," Winslow wrote in a chat. Winslow told Laws he would come to Alaska and work as the man's housekeeper; in exchange, Winslow would have access to the children. Their chat went this way:

Lovethemcute: its a shame they have to feel guilty or schools tell them its wrong

Laws, working undercover: yea but what are you going to do

Lovethemcute: I agree its wrong to abuse a child but we don't abuse them there is a difference

Lovethemcute: just have to raise them to think its fine and not to tell anyone

Lovethemcute: what is done in the family stays in the family

A 'FUN BOY'

When authorities searched Winslow's home and took his computer, the warrant allowed them to look only for items related to the sending and receiving of child-exploitation images and the chats and emails between Winslow and the undercover agent. Nicole Eason was no longer living with Winslow.

Not until he was contacted for this story did Laws, an agent who specializes in protecting children, learn about the Internet groups that facilitate private re-homing. At the time he caught Winslow, Laws says, authorities didn't know to look for anything beyond what was in the chats.

After a reporter told Laws about the 10-year-old whom Winslow and Eason had taken in, the agent re-examined his exchanges with Winslow. Among the items Laws discovered was a photo of the boy, clothed.

Reading from a transcript that wasn't made public as part of the criminal case, Laws says Winslow also described the 10-year-old. Winslow called him a "fun boy" whom he and his ex-girlfriend planned to adopt.

In February 2008, Winslow pleaded guilty in his criminal case and was convicted of sending and receiving child pornography from June 2006 through May 2007. The span includes the months that the 10-year-old spent with Winslow and Eason. Serving a 20-year sentence at a federal prison in Elkton, Ohio, Winslow declined requests for an interview.

After returning to Wisconsin, Mueller sent the child to another home after getting approval from child welfare officials.

The boy turned 18 a few days ago. In an interview, his new foster mother said he is one of 10 children with special needs that she and her husband are raising. She said he is often combative and uncommunicative. He once asked if he could attend a school for troubled children, she said, but she and her husband insist on home-schooling him and don't believe in therapy for children. The couple declined to make the boy available for an interview.

'PERFECT TOGETHER'

Asked recently whether she knew that Winslow is in prison for trading child pornography, Nicole replied "nope" and said she knew Winslow "for like a couple weeks." She also disputed that Winslow traveled with her to pick up the boy, despite the photographic evidence to the contrary.

In emails that Nicole Eason and Mueller exchanged shortly after the handover, Eason wrote that the boy and Winslow "are perfect together… both playful kids which is what (the boy) needs."

In an earlier interview, Nicole Eason didn't mention Winslow but did refer to the child as "our sex boy." He often behaved perversely, she said: "He would try to walk around butt-naked."

When the boy misbehaved, she said, she had "no problems spanking an ass." Once, she said, she hit him when he insulted a customer at a Walmart.

"As weird as this sounds, I just unnaturally reacted and backhand him in his mouth," Eason said. "You know, busted his lip with his tooth and, you know, he started crying."

By early 2007, the boy had gone, and Nicole and Winslow had parted. She was again living with Calvin. And again, she had connected with two sets of parents who didn't want their children, a Russian boy and an American girl whom the Easons would take.

Big Momma also was becoming a bigger presence in the Internet re-homing forums. Soon, a woman who moderated one of the bulletin boards grew concerned about Nicole – so much so that she drove through the night to the Eason home. She was there to try to take the boy and girl away from them.

International adoptions: frequently asked questions

How does an American family adopt a child from abroad?

- Ninety countries belong to the Hague Adoption Convention, a set of safeguards for international adoptions. As a member, the United States requires parents to take 10 hours of training before adopting from another member country, such as China. (There's no requirement when adopting from a non-Hague country, such as Ethiopia.) When Americans adopt children from U.S. state foster-care systems, more training is required: typically 30 hours.

- In about half the cases, involving kids from Hague countries, the adopting parents go through a federally accredited U.S. adoption agency that works with authorities in the foreign country. In the other half, involving non-Hague countries, families might go through an American adoption agency or work directly with facilitators in the child's home country.

- Some international adoptions are approved in a foreign court; others in a local U.S. court. In foreign-court adoptions, no authority checks on the child in the new home. In U.S.-court cases, the family may face monitoring by a social worker for around six months.

- Some countries require periodic reports on the child's well-being in their new homeland. Violators face little risk. A foreign country can cut off the agency involved, but has no recourse against the adoptive parents. An agency can sue a family for breach of contract. But that rarely happens.

What help is available for a family struggling with a troubled foreign adoptee?

- Not much. Some agencies provide post-adoption support to families, but they aren't required to, and many don't.

- Many U.S. states provide help to families who adopt troubled children from the state's own foster system, such as counseling or temporary placement outside the home ("respite"). But this support usually isn't available with internationally adopted kids.

- Private alternatives, such as residential treatment centers, are available, but they can cost thousands of dollars a month.

What if a family wants to send its adopted child back to the agency?

- If the child is from a Hague country, and the adoption is still pending approval in a U.S. court, federal law requires the agency to maintain legal custody of the child until it finds another family.

- If the adoption is final, the agency has no responsibility to help. Most don't help parents offer a child for re-adoption.

- Parents can try to relinquish a child to a state's child-welfare system. But this is difficult. In many states, these parents must be investigated for abuse and neglect. If the state takes the child, often parents must pay for the child's care until he or she is re-adopted.

How can a family find a new home for their adopted child?

- A few U.S. adoption agencies assist with "re-homing." They will help find a new family for the child, but don't take legal custody or monitor the transfer. This is a gray zone: The agencies say they are simply facilitating private direct adoptions between two families and their lawyers.

- There are Internet forums, such as Yahoo groups and Facebook pages, that facilitate re-homing. This is a gray zone, too, and it is the focus of this series. Families place informal ads for children needing new homes; adults advertise a desire to take in a child. This activity may violate state laws that prohibit anyone except licensed child-placing agencies from facilitating an adoption or advertising a child's availability. After connecting online, families can move forward with a re-adoption or a transfer of guardianship.

What kinds of re-homing are possible?

- The families can seek a formal re-adoption. This requires court approval – and affords the most protection for the child. The original adoptive family must terminate parental rights. The new family submits to a criminal background check and additional vetting by a social worker.

- The families can try to transfer guardianship in court. The original adoptive parents don't terminate parental rights. The new guardians may have to undergo a background check.

- The families decide to transfer custody of the child in a less formal way, with no court involvement. The original adoptive family signs a piece of paper granting the new family power of attorney over the child for a period of time. Once notarized, this document allows the new family to enroll the child in school and secure government benefits for the child. In many cases, this is a gray zone: The transfer takes place out of the view of the child-welfare and court systems. The document isn't officially recorded anywhere. This is a preferred method for families seeking a temporary, out-of-home placement for the child – often called "respite." In other cases, it is used to transfer custody of a child for years at a time.

Are there laws against informal custody transfers?

- There's a partial safeguard, and it's weakly enforced. When a child is transferred across state lines for re-adoption or new guardianship, the families must secure the approval of authorities in both the sending and receiving state. Failure to do so violates the Interstate Compact on the Placement of Children – a legal agreement among the U.S. states. If authorities learn of an illegal transfer, they can remove the child from the new home. They also can take legal action against the adults involved, but this rarely happens.

What is the Interstate Compact on the Placement of Children, and how does it apply to custody transfers?

- The compact, often called the ICPC, is an agreement adopted as law by all 50 U.S. states, the District of Columbia and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Generally, the ICPC requires that authorities in both states be notified when custody of a child is transferred from one state to another. If authorities aren't informed, the adults involved in the transfer have violated state law in both states. The catch: How – or even whether – authorities enforce the law differs by state. In some states, violations are considered crimes, typically misdemeanors. But other states aren't explicit about how violators of the ICPC should be punished.

Source: Reuters

With blind trust and good intentions, amateurs broker children online

Part 3: A woman thought she was helping find better homes for unwanted adoptees. Duped by one couple, she tries to rescue a Russian boy and an 8-year-old girl.

HICKORY, North Carolina – When Megan Exon began moderating an Internet bulletin board in 2007, she viewed her effort as a way to help kids find better homes.

The group was called adoption_disruption, and it drew parents who were struggling to raise children they had adopted.

The North Carolina woman wasn't a licensed social worker or an adoption specialist. She was a 41-year-old mother who had taken in a child herself less than two years before. Her husband had noticed a Taiwanese boy advertised on the Internet, in one of the online forums that support America's underground market for unwanted adopted children.

The parents who were giving up the boy told Exon that the 4-year-old's feet were too big and his ears looked funny. If parents could discard their adopted kids so callously, she reasoned, maybe she could help children find new families by moderating one of the Internet sites.

"We were just introducing people," Exon says of the online group, where parents sought new homes for unwanted children in a practice known as "private re-homing."

"The only thing we facilitated," she says, "was bringing people together."

Well-intentioned as that seemed, Exon would come to regret her role in the re-homing network, a collection of Internet forums where people seeking children can find one quickly. They are able to do so without involving the government and sometimes with the help of middlemen whose activities can be naïve, reckless or illegal, a Reuters investigation has found.

Exon grew alarmed on April 5, 2007, when she took a phone call from Lynne Banks, a woman in South Dakota who followed the activity on the online adoption boards. Banks warned of an Illinois couple using the Internet to obtain children. The woman sometimes called herself Big Momma. Her real name was Nicole Eason.

In her conversation with Exon, Banks said she believed that Eason and her husband, Calvin, were lying about being approved by the government to take in children. While surfing the Internet, Banks also came to suspect that a man who'd been living with Nicole was possibly a sex offender.

Exon knew of the Easons. They already had sought children on the Internet group. She had introduced them to two families. One lived in California. They had recently sent their daughter, an American-born girl who was about to turn 8, to live with the Easons. The other had sent them a teenager, Dmitri, a boy who had been adopted in Russia.

"I was absolutely stunned," Exon recalls. She also was terrified.

"I felt like we were participating in something that was getting out of hand," she says today. "We weren't doing background checks. We didn't have any way of knowing who these people were.… I felt sick to my stomach."

Even then, Exon had no idea what sort of parents the Easons had been: Child welfare officials had taken away Nicole Eason's two biological children, a son and a daughter, years earlier. A report by authorities who removed the Easons' newborn son characterized them as having "severe psychiatric problems" and "violent tendencies." And the man Banks had mentioned – the one who had been living with Nicole – had been trading pictures of naked children online.

After she got off the phone with Banks, Exon felt she had to act fast. That night, she and a friend would pack their children into a van and drive about 650 miles northwest, to a baby-blue cinderblock house that the Easons rented in Danville, Illinois.

"Oh my God," she told the friend, "we've got to get those kids."

'THE WAY THE INTERNET IS'

For prospective parents, the draw of re-homing is obvious: They can bypass some of the most basic but time-consuming government safeguards meant to protect children.

To legally take custody of a child through the U.S. foster care system, prospective parents undergo criminal background checks, home inspections, and in most states, dozens of hours of training. After placement, social workers visit the family regularly to ensure the child is safe. In many private re-homings, none of that happens.

The online bulletin boards have emerged as a do-it-yourself way for parents to quietly end adoptions. The groups not only attract parents but also appeal to do-gooders like Exon who delight in the chance to help find needy children better homes.

On one bulletin board, Adopting-from-Disruption, Reuters found dozens of advertisements for children that appear to be posted by middlemen. Few were licensed child welfare workers. Some had taken in or re-homed children themselves. Yahoo took down the group after Reuters told it what was going on there. The company also took down five other groups that Reuters brought to its attention.

One relatively new re-homing group is a Facebook page called Way Stations of Love. It was founded last year by Tim Stowell, a 60-year-old father of four adopted children who works at a Tennessee boarding school for boys. Facebook says activity on the page is "a reflection of society."

Stowell says Way Stations serves a dual purpose: to support distressed parents to avert re-homings, and to help find new families for children if necessary. "Every time a child moves from home to home," Stowell says, "it puts a dent into their psychological well-being."

Today, the group has about 275 members. Its Facebook classification is "secret," meaning only members can see it; others need Stowell's permission to join. He says he also keeps a private list of people willing to take in children from failed adoptions. But like most go-betweens, Stowell says he leaves the vetting of prospective parents to families offering a child.

In some cases, he says, parents meet on the site and exchange private emails to arrange custody transfers. "And then I never know what happens to them," Stowell says of the children. "Some people want the children as far away from them as possible."

On Way Stations of Love, intermediaries regularly offer assistance. "Posting for a friend," a North Carolina woman wrote in June. "8 Year old Guatemalan female Resides in North Carolina with her family Adopted at 8 months into current family…"

Many advertisements for unwanted children skirt a patchwork of state laws that define who can place children and how. In some form, 29 U.S. states have laws that govern how children can be advertised for adoption. In many of those states, those helping to arrange an adoption must be licensed to do so.

In Tennessee, no law prevents Stowell from advertising children for adoption, or from helping parents find available children. But Stowell says he isn't certain whether other middlemen who facilitate such transfers online are breaking the law. "They may be," he says. "I don't know that state laws have kept up with the way the Internet is. I'm hoping that people will obey the laws of their different states, whatever they may be."

Idaho is a state that does restrict who can advertise adoptions. There, a statute prohibits those without a state license from advertising children for adoption or from conveying "the ability to place, locate, dispose or receive a child or children for adoption."

One online roster of available children is kept by an Idaho-based non-profit organization named Christian Homes and Special Kids, or CHASK. The group has been helping match children with new parents for almost a decade. It has no state license or contract.

"We're just trying to help families," says Tom Bushnell, a lawyer who founded the group with his wife, Sherry.

Most of the children listed by the group for re-homing come from failed international adoptions, and a disclaimer on its website reads: "CHASK should be considered a 'last resort' avenue for finding a new adoptive home for a previously adopted child."

Initially, regulators were unfamiliar with CHASK. After Reuters inquired more recently about the organization, a spokesman with the Idaho Department of Health and Welfare said late last month that the state attorney general began a review. At issue: "the scope of CHASK's activities and if they are complying with Idaho law," the spokesman said.

Tom Bushnell says CHASK isn't violating Idaho's law on advertising children for adoption, in part because the computer server the group uses is located in another state.

THE LITTLE GIRL

When Exon became a moderator of adoption_disruption, the re-homing group on Yahoo, she was essentially its gatekeeper. Moderators review prospective members and are often the first to see ads for unwanted children. They can orchestrate connections between participants and control the group's settings, including whether to make messages public or private.

Exon says she just wanted to help improve children's lives. She had helped run summer camps and afterschool programs while working for a school board in Florida. Moderating the group seemed like another opportunity to serve.

In 2007, Exon came across Nicole Eason for the first time. Eason's posts in the re-homing group seemed sincere. Nicole explained that she and her husband had taken in children through the U.S. foster care system, Exon recalls. Eason also wrote that Illinois officials had confirmed that they were suitable parents.

Like moderators on other re-homing sites, Exon didn't see vetting prospective parents as her responsibility. After initial connections were made on her bulletin board, it was up to the two families to do due diligence.

"We always reminded people, 'Get an attorney,'" Exon says. "And obviously people didn't always do that."

She and Nicole Eason spoke on the phone a few times, and she says she could tell the Easons badly wanted children. Exon understood that passion to parent; she also saw many adults on the bulletin board who wanted to get rid of kids.

One was the California couple who turned to adoption_disruption in early 2007. The parents were eager to find a new home for their adopted daughter. Exon suggested they connect with Eason.

"I can tell you for a fact that I was the one who introduced them," she says today.

For Nicole Eason, acquiring the girl was easy. "I seen three pictures of her, talked to her on the phone twice, and spent an hour with her before she was all mine," she said in an interview.

RUSSIAN TEEN

Adoption_disruption was also where Eason connected with William and Victoria Stewart, an American couple living in Scotland. The Stewarts were looking to re-home Dmitri, a 14-year-old they'd adopted from Russia 11 years earlier.

Dmitri, now 20, says his relationship with his adoptive parents had broken down after the Stewarts had three children of their own. He recalls he was constantly getting in trouble. William Stewart says Dmitri was emotionally detached and would grow enraged easily.

The family had moved to Scotland from Florida, Stewart says, to avoid child protective officials there who had investigated him and his wife for allegedly abusing Dmitri. They weren't charged, but the experience made them reluctant to reach out to government social services after concluding they could no longer raise Dmitri. Stewart says he stumbled upon the adoption_disruption Yahoo group while surfing the Internet.

Of the bulletin board, Stewart now says this: "There was some crazy stuff going on. People weren't who they said."

Stewart had never reviewed any records attesting to the suitability of the Easons when he flew to Illinois in March 2007 to drop Dmitri with the couple. He says Exon was the "total middle person" in the transfer, and he was relying on her recommendation.

The 8-year-old girl from California was already there, recalls Dmitri. (The girl's name is being withheld because she is a minor.)

The house in Danville didn't resemble the description in a "home study" that Nicole once posted online: "The home is tastefully furnished," the document reads, "and housekeeping standards are good."

"It was really decrepit," Stewart says, adding that he "was really torn" about leaving Dmitri there.

As Dmitri recalls, the rented cinderblock house had almost no furniture and the sink was piled with dirty dishes.

Strangely, none of the bedrooms had doors. Dmitri asked Nicole why. "I like to watch you sleep," Dmitri says she told him. Her answer, he says, made him feel "really weird."

Dmitri had no idea how long the 8-year-old girl, with shaggy brown hair and a wide smile, had been living there. He didn't know where she had come from, either. He says that she slept in the Easons' bed.

The Easons never made him go to school, he says, so he sat home and smoked cigarettes they gave him. A picture taken in Danville shows Dmitri perched on the front steps of the house, a cigarette and a water bottle in his left hand. He wears a striped soccer jersey, dark pants and a blank expression.

In an interview, Nicole Eason took issue with Dmitri's account. She said his bedroom had an accordion-style door, that she never bought him cigarettes, and that the girl living there never shared the Easons' bed.

RED FLAGS

On April 5, 2007 – a few weeks after Dmitri was dropped there – a police officer knocked on the Easons' door. Lynne Banks, the woman who contacted Exon about the Easons, had called authorities.

Browsing the Internet groups, Banks came across posts from Nicole Eason. They didn't add up, Banks thought: Eason referred to children she didn't have and others who she claimed had died.

Banks says she began reaching out to parents who'd been contacted by Eason. Later, she came across the home study Nicole circulated. As far as she could tell, the Easons had simply typed information into a sample document that was posted on the Internet. She also found that a man named Randy, who had posted a profile on an adult sex site, may have taken a child with Nicole. (That man, Randy Winslow, was later convicted of trading child pornography.)

"Red flags were popping up," Banks recalls. She reached out to Exon to relate what she had found. Then, Banks called the Danville Police.

The officer who visited the house spoke briefly to the children, and "both indicated that there were no inappropriate contacts or abuses," the police report says. The Easons also produced "Authorization of Legal Guardianship of Minor" documents for both children, and insisted they were treating the kids well.

The police took no further action. Exon did.

'YOU'RE NOT SAFE HERE'

Exon says that after talking to Banks, she couldn't stop worrying about Dmitri and the girl. She reached out to both sets of parents, and says they gave her permission to retrieve the children.

Within hours, Exon was heading to Illinois. Behind the wheel of the red van was a friend Exon had met through the Yahoo group who had recently taken in two children through re-homing. The two brought their children along on the 10-hour drive.

Before leaving, Exon got Nicole Eason on the phone and announced she was coming for Dmitri and the girl. Nicole seemed willing to turn them over, Exon says.

Still, as Exon arrived at the small house the next morning, she didn't know what to expect. She had never met the Easons, not in person.

Exon knocked on the door. A burly man answered. At around 6-foot-2 (1.9 meters), Calvin Eason stood more than a foot (30 cm) taller than she did.

Behind him, Exon saw a young girl with greasy hair and filthy clothes, and a teenage boy with a cigarette dangling from his mouth. Something – a mouse? – lay on the floor. It was covered in bugs, she remembers. Nicole wasn't around.

Exon composed herself. She was here for the girl, she told Calvin Eason.

Then she turned to Dmitri. "You're coming, too," she said. "You're not safe here."

Neither child had seen her before.

"You're on private property," Eason recalls telling her. "I'm gonna have to ask you to leave."

"Well, I'm not leaving without her," she replied, Eason says. "I'll have the authorities come here and escort her out."

Calvin relented, and Exon says he told the children to grab their belongings. Dmitri was reluctant to go. He didn't know this woman or what she wanted with them.

"It was all very sudden," Dmitri recalls. "I knew I wanted to leave but … it was really crazy."

Exon thought fast and remembered something Dmitri's adoptive father had told her. She promised to buy the boy a hamburger if he came along. It worked.

Just before Exon left, Calvin tried to get her to take a puppy he and Nicole had gotten for the girl, a pit bull that the 8-year-old named Cinderella. Exon refused.

None of these custody transfers were valid – not the Easons taking in the children, or Exon and her friend keeping the kids without involving state officials. Each step violated the Interstate Compact on the Placement of Children, which requires authorities to sign off when custody of a child is transferred across state lines.

In the weeks after Exon picked up the children, the Stewarts and the 8-year-old's parents made clear they didn't want their kids back. Exon's friend from the Yahoo group took Dmitri to her home in Georgia and cared for him for a short time, before handing him over to the Georgia child welfare system.

Dmitri was placed in a government-approved foster home. William Stewart says today he and his wife were allowed to disown Dmitri after agreeing to pay for the boy's care until he turned 18. Dmitri left the foster home this year. He still uses the last name Stewart.

As for the 8-year-old girl, Exon couldn't give her up. She has since gone to court to legally adopt the girl, and says the adoption is almost final.

Exon says she stopped moderating the re-homing bulletin board immediately. "After what happened with the Easons, I felt like maybe we were doing something wrong," she says. "I didn't want to be a part of it anymore."

The Easons became more involved. Within months of Dmitri and the girl leaving, Nicole Eason established her own re-homing group on Yahoo. She called it abig_hug_needed. Instead of Big Momma, she now took the screen name momma_bear2000.

"Did You ever imagine this day would come, where you have no other choice but to disrupt the adoption you longed for," Eason wrote. "This group is for support, resourses or just plain chat. Tell your experiences, Post a message looking for a new home for your special child or Ask a question about disruption. We learn by sharing of thoughts, experiences, and our feelings."

A few weeks later, two new girls would pass through the Eason household. Both had been born overseas. Both had been advertised on an Internet bulletin board.

By 2009, the Easons would also take custody of a 5-year-old boy born in Guatemala. This time, the boy's adoptive father wasn't simply a distraught parent looking to end an adoption.

He was a cop.

Source: Reuters

Despite ‘grave danger,’ government allows Internet forums to go unchecked

Part 4: Parents bypass weak laws and authorities don’t enforce them. A police officer gives away his adopted son. ‘It could have been Hannibal Lecter.’

TUCSON, Arizona – Tom and Misty Mealey brimmed with hope as a battered purple pickup pulled up to their Virginia home.

It was July 5, 2009, and their houseguests had arrived – a husband and wife who had driven from upstate New York to the Mealey residence just outside of Roanoke.

Until that day, the Mealeys hadn't met Calvin Eason, then 40, or his wife Nicole, 30. Both were "shabbily dressed," and they didn't immediately impress, Misty Mealey recalls. Still, if all went well, the Mealeys were prepared to give the Easons one of their children: a 5-year-old boy they had adopted from Guatemala months earlier.

The boy suffered from a condition called reactive attachment disorder, which makes bonding with caretakers difficult. He had grown increasingly violent, breaking windows, hitting the Mealeys' three other children and urinating on their toys. At night, the Mealeys locked him in his room to keep their family safe.

After months of therapy and other attempts to get help, the Mealeys did what distressed parents across America continue to do: They began advertising their unwanted adopted child online.

The Easons responded quickly, stressing in emails and phone calls that they would be excellent parents. Then they drove more than 600 miles to make their case to the Mealeys in person.

The Easons shared meals and went bowling with the family. They also seemed to bond with the 5-year-old. He crawled on their laps and they played with him. He even "spontaneously started calling them Mom and Dad," Misty says today.

"They seemed very comfortable around children," she recalls.

Before week's end, the Mealeys were convinced, and Calvin and Nicole Eason headed back to New York with the 5-year-old.

Like others who find new parents for their child on the Internet, the Mealeys had been distraught. They, too, didn't involve child welfare authorities in the custody transfer, and they knew little about the parents taking their child.

For all their similarities to previous parents who gave children to the Easons, the Mealeys were unique. Tom Mealey was trained to spot deception.

He was a police officer.

The story of how the Easons acquired boys and girls through the Internet exposes almost every way in which authorities fail to crack down on those who use America's underground child exchange, a Reuters investigation has found.

Without involving government officials, parents transfer unwanted children – often foreign adoptees – to virtual strangers they meet online. No law explicitly covers the practice, a type of "private re-homing." The primary safeguard that does exist is a feeble deterrent – an agreement between U.S. states called the Interstate Compact on the Placement of Children (ICPC).

Although the ICPC has been adopted as law by each state, some states attach no penalties to violations of the pact. In others, violations are considered misdemeanors, but even then officials almost never prosecute offenders. Many police are unfamiliar with the ICPC. Authorities who do understand the compact say they are focused on helping children rather than enforcing the law.

"Speaking honestly, we wouldn't be that concerned about the penalty for the person who violated the compact," says Harry Gilmore, deputy administrator of the ICPC in Oregon. There, a violation is a misdemeanor.

For parents who know about the compact but choose to ignore it, any legal risk is outweighed by the need to remove a troublesome child. When the underground network is used, a transfer will likely go unnoticed by authorities, minimizing the chance of getting caught. The only people vetting a child's new family are the adoptive parents themselves – the very people looking to get rid of the boy or girl.

Two families who gave their children to the Easons – the Mealeys of Virginia and Gary and Lisa Barnes of Texas – came to realize the dangers of handling such transfers themselves.

"It's horribly embarrassing," Tom Mealey says of being misled by the Easons. "The thought that I spent a career dealing with people like this is even more embarrassing. I wish we had done more."

"We're thankful that it was just the Easons," he adds. "It could've been Hannibal Lecter."

'A USED CAR'

In August 2008, almost a year before taking the Mealey boy, the Easons found a new child online to join their household. Anna Barnes was 13. She had already been re-homed once since she was adopted in Russia and brought to the United States at age 7.

Her second set of American parents, the Barneses of Tolar, Texas, had come to regret adopting Anna. They had talked with her original adoptive parents before taking custody. But the Barneses quickly suspected that they hadn't been told enough about the emotional and behavioral problems Anna brought to America.

"This is a bad analogy, but it's sort of like selling a used car," Gary Barnes says of why he and his wife weren't told more. "If you tell someone it breaks down every day, nobody's going to buy it."

The Barneses, who breed miniature horses for a living, found Anna to be defiant. Counseling proved too expensive and inconvenient. A home for troubled kids told them she wasn't a good fit for its program. If they turned Anna over to the state of Texas, the Barneses say they were told, they would be considered unfit parents and have to pay child support until she turned 18.

"We spent the first year trying to help the child and fix the problem," Gary says. "Then a light comes on and you realize you can't fix the problem, that you need to get away from the problem."

The Barneses wrote an ad about Anna and posted it online, in a Yahoo forum called Respite-Rehoming.

Nicole Eason, who was going by the name Momma Bear online, replied. In emails with the Barneses, she pledged that she and her husband were prepared to care for Anna.

"We will love her no matter what mistakes she makes in life," Momma Bear assured the Barneses. She promised to buy Anna her favorite candy – Heath bars – and give her a puppy, an inducement the Easons had used before and would use again.

"I gotta tell you, you're hitting a home run with everything that you're offering up to her," Lisa Barnes replied. The "puppy thing was a good idea… It will give her something to focus on instead of thinking all bad or 'poor me' thoughts."

To help clinch the deal, Nicole shared a fictitious "home study" she created. In it, a social worker purportedly vouched for the Easons' parenting skills.