Bricked-up cellar may yield truth of child abuse scandal

By Jerome Taylor in Jersey and James Macintyre, Tuesday, 26 February 2008

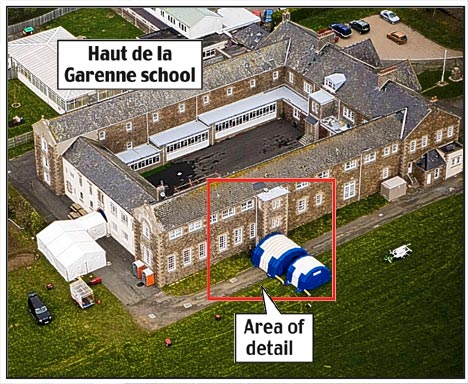

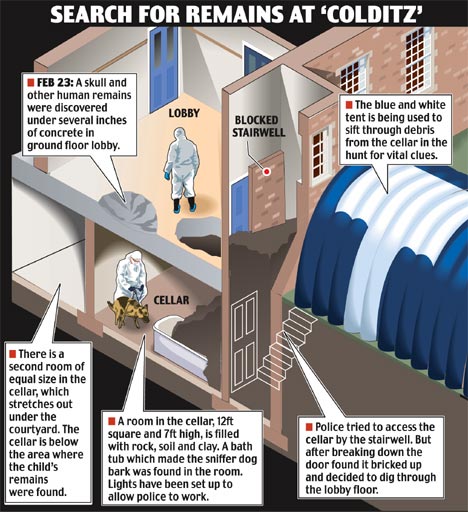

A bricked-up cellar at a former care home in Jersey is being examined by forensic experts after a child's remains were found at the weekend, following claims of abuse at the premises stretching back five decades. Detectives say the search could last up to two weeks after sniffer dogs gave positive "indications" at six other locations within the building.

Amid speculation that more bodies may be found at the property, the island's deputy chief of police, Lenny Harper, told the Jersey Evening Post: "We always hoped it would not end like this but, from the information we were getting, it was always a possibility. We are very interested in the cellar because we do have allegations that offences were committed in a cellar and we think we know where that cellar is."

There were accusations of a cover-up yesterday after it emerged that several bones were found in 2003 by builders renovating the former children's home, but the remains were written off as being animal bones and the case was closed.

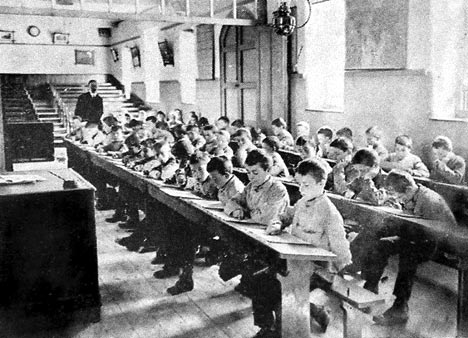

Haut de la Garenne, built in 1867, is known as the setting for the BBC detective series Bergerac. In the 19th century, it originally served as an industrial school for "young people of the lower classes of society and neglected children", before becoming a care home by 1900. It was an orphanage and correctional facility until its closure in 1986. In 2004, the house was turned into a 100-room youth hostel after a £2.25m refurbishment. The majority of the alleged assaults are believed to have taken place between the 1960s and 1980s.

Police say they have been contacted by 150 people claiming to be victims of abuse or witnesses to it at the centre. The NSPCC said it had received 63 calls from people claiming they were abused in Jersey care homes, 27 of whom have been referred to detectives. Detectives made their first gruesome discovery on Saturday afternoon, when a child's remains, believed to be a skull, were found at the youth hostel in St Martin on the north-western tip of the Channel island.

Mr Harper said the inquiry would look into why reported cases went unanswered. "Part of the inquiry will be the fact that a lot of victims tried to report their assaults but ... they were not dealt with as they should be," he said. "We are looking at allegations that a number of agencies didn't deal with things as perhaps they should."

As a result of the recent publicity, he added, several people had reported being abused in care on Jersey between the ages of eight and 10, adding to the police tally of 140 possible victims.

Stuart Syvret, Jersey's former Health minister, who claims he was sacked for revealing the extent of child abuse on the island, has accused Jersey's government of a cover-up, although Mr Harper said he had seen no evidence of that. Speaking on yesterday's Radio 4 Today programme, Mr Syvret alleged that a "culture" of cover-ups went "as far as the very top of Jersey's society".

Comments picked up after a radio interview between the island's chief minister, Frank Walker, and Mr Syvret highlighted the growing tension on the island. After the end of the interview in their Jersey studios Mr Syvret turned on his former political colleague and exclaimed: "We're talking about children here." Mr Walker responded: "You're trying to shaft Jersey internationally."

A free helpline set up by the NSPCC at the request of police has received 63 calls from adults reporting allegations of physical, sexual and emotional abuse dating back to the 1970s and 1980s. Police said that records of children at Haut de la Garenne were "patchy". It is understood that those who died in care may have been reported as runaways.

Although officers have not confirmed where in the hostel they are digging, the cellar at the back of the building – which was covered with a white tarpaulin tent yesterday – is believed to be the main focus of the investigation. Three witnesses have told police that child abuse took place in the cellar many times during the 1960s and 1970s.

The investigation began in November 2006 but detectives kept their inquiries secret for more than a year in order not to alert those suspected of carrying out the attacks.

One Scottish resident, who has lived on the island for eight years, said: "There have been rumours of child abuse for years ... But you don't expect it to happen on a wee little picturesque island like here."

History of Haut de la Garenne

- 1867: Haut de la Garenne first built.

- 1900: Renamed the Jersey Home for Boys, the centre houses youngsters with special needs, serving as a school and orphanage.

- 1986: Home is closed.

- 2004: Reopens after a £2.25m refurbishment as Jersey's first youth hostel.

- 11 September 2007: Stuart Syvret sacked as a health minister after criticising ministers and civil servants over childcare.

- 22 November 2007: As reports emerge of systematic abuse at the home, police investigate the treatment of boys and girls aged between 11 and 15 since the 1960s, as well as links with the Jersey Sea Cadets.

- 30 January 2008: Charges brought against a man linked to the home for indecently assaulting three girls under 16.

- 19 February 2008: A full-scale police excavation begins at the home.

- 23 February 2008: A sniffer dog discovers human remains and shows "indications" at six other sites at the home. The remains are sent for tests.

Source: Independent (UK)

25/02/08 - News section

Haut de la Garenne: Why abuse on this level could happen again

By DEMETRIOUS PANTON

My mouth went dry and my fists clenched when I heard about the remains found in Jersey.

I felt sorrow and rage that police are once again belatedly investigating a huge paedophile ring based on care home kids, and expect to dig up more bodies.

A ring of evil men exploited the most vulnerable children imaginable for up to 40 years, and no one stopped them.

It is emerging now that the victims repeatedly begged for help. Why did no one listen?

I have a pretty good idea why not, given how viciously the politically-correct establishment silenced me about the similar paedophile ring which raped me.

I was sexually abused by two male workers in children's homes in Islington, North London, in the late 1970s and early 1980s. I was unusual, a kid who did not seek escape through drugs or suicide.

But I did run away and never again attended school. I spent my days at my local library, educated myself and went on to university, desperately hoping I could make someone listen. No-one did.

Throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, I wrote reports on my abusers, demanding an inquiry.

In 1992, I even lobbied Margaret Hodge's office - she was then council leader - and met her stand-in, Stephen Twigg, now also a Labour MP. He did nothing.

The truth only emerged thanks to a three-year newspaper campaign which revealed that all of Islington's 12 children's homes were run by, or included, staff who were paedophiles, child pornographers or pimps.

How did this come about? Child care was - and remains - underpaid and undervalued. Sadists easily acquire jobs when no one else wants them.

But there was another insidious factor in Islington - one which I fear leaves other children at equal risk today.

The far-Left council had actively recruited men who claimed to be gay to run its homes, and declared that "gays" did not even need references or professional training or experience.

But the men who flocked forward were not gay - they were paedophiles.

A 1995 Government-ordered inquiry confirmed that no action was taken against these evil men because "the equal opportunities environment, driven from the personnel perspective, became a positive disincentive for bad practice".

In plain English, anyone who raised abuse concerns about the men running its children's homes was "anti gay".

And I was written off as "insane".

In 2003, when Tony Blair shocked many by appointing Margaret Hodge as Children's Minister, she tried to halt a media investigation into her Islington history by claiming I was "extremely disturbed".

She eventually had to apologise to me in the High Court. I was by then a Government adviser, producing reports for the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister.

In Jersey, the victims now coming forward are said to be furious that their earlier pleas for help were ignored. Murder was committed, but no one lifted a finger.

I have always believed only the surface of the corruption in Islington was scraped. An immensely brave social worker who blew the whistle on the scandal told me early on that other victims talked of children being killed. But they were too afraid to give details. None of those allegations was ever investigated.

Let us not kid ourselves that such horrors could never happen again. People may be more vigorously vetted, and complaints taken more seriously, but paedophiles can offend against hundreds before they acquire a criminal record because children are easy to intimidate and ensnare.

The Islington scandal should have shamed social workers out of naive political correctness, but it has not.

Children today in need of care are most likely to be placed with foster parents, rather than in homes.

That does not mean there is no risk, just that victims are more isolated. Consider how many councils now boast of their active commitment to recruiting gay foster carers.

Are they bright and brave enough to distinguish between genuine gay men - who would not dream of hurting children - and paedophiles who cynically hide behind the gay rights banner?

I am not convinced - I know of one foster care manager jailed in 2005 for the sexual abuse of boys in care.

Scandalously, the council responsible - one of Britain's most gay-friendly - has still held no inquiry into whether he was recruiting other paedophile friends as "carers".

So how can anyone be sure the children he placed are safe?

Source: Daily Mail

'I have known about Jersey paedophiles for 15 years,' says award-winning journalist

By EILEEN FAIRWEATHER - More by this author » Last updated at 11:13am on 2nd March 2008

The award-winning journalist who exposed terrible abuse in Islington children's homes now reveals horrifying links to sinister discoveries at Jersey's Haut de la Garenne.

I met the frightened policeman at an isolated country restaurant, many miles from his home and station. Detective Constable Peter Cook had finally despaired, and decided to blow the whistle to a reporter.

He was risking his career, so made me scribble my notes into a tiny pad beneath the tablecloth.

He had uncovered a vicious child sex ring, with victims in both Britain and the Channel Islands, and he wanted me to get his information to police abuse specialists in London.

Incredibly, he claimed that his superiors had barred him from alerting them.

He feared a cover-up: many ring members were powerful and wealthy. But I did not think him paranoid: I specialised in exposing child abuse scandals and knew, from separate sources, of men apparently linked to this ring.

They included an aristocrat, clerics and a social services chief. Their friends included senior police officers.

Repeatedly, inquiries by junior detectives were closed down, so I, a journalist, was asked to convey confidential information from one police officer to others. It seemed surreal.

I duly met trusted contacts at the National Criminal-Intelligence Squad. That was more than 12 years ago, and little happened - until now.

Last weekend, a child's remains were found at a former children's home on Jersey amid claims of a paedophile ring.

More than 200 children who lived at Haut de la Garenne have described horrific sexual and physical torture dating back to the Sixties.

When I heard the news, my eyes filled with tears. I felt heartbroken, not least at my own powerlessness. I have known for more than 15 years about Channel Islands paedophiles victimising children in the British care system.

I was relieved that the truth was finally emerging. But I felt devastated. Children had probably been murdered. I had so not wanted to be right.

I stood outside the forbidding Victorian building of Haut de la Garenne this week and watched grim-faced police in blue plastic forensic suits hunt its bricked-up secret basements for children's bones.

Outside, a large cross commemorates the 35 former residents who died fighting for their country: "Their names liveth forever." Oh yes?

What are the names of the children whose bodies may now be dug up - and why did no one miss and search for them earlier? Jersey's residents and political class must ask these questions.

Disturbing allegations about the murder of children in care have characterised other scandals I investigated in Britain, but today I can reveal for the first time the links between the abuse I uncovered at care homes in Islington, North London, and the horrifying discoveries on Jersey.

I have never before written that 14-year-old Jason Swift, killed in 1985 by a paedophile gang, is believed to have lived in Islington council's Conewood Street home.

Two sources claimed this when I investigated Islington's 12 care homes for The Mail on Sunday's sister paper, the London Evening Standard, in the early Nineties.

But hundreds of children's files mysteriously disappeared in Islington and, without documentation, this was not evidence enough.

We did, however, prove that every home included staff who were paedophiles, child pornographers or pimps. Concerned police secretly confirmed that several Islington workers were believed "networkers", major operators in the supply of children for abuse and pornography.

Some of these were from the Channel Islands or regularly took Islington children there on unofficial visits. In light of the grisly discoveries at Haut de la Garenne, the link now seems significant, but at the time we were so overwhelmed by abuse allegations nearer home that this connection never emerged.

What we did report prompted the sort of vehement official denials that have come to characterise child abuse claims. Margaret Hodge, then council leader, denounced us as Right-wing "gutter journalists" who supposedly bribed children to lie.

Our findings were eventually vindicated by Government-ordered inquiries, and two British Press Awards. Yet I knew we had only scraped the surface of Islington's corruption.

Now Jersey police under deputy chief Lenny Harper - a 'new broom' outsider - have been secretly investigating a paedophile ring linked to the island's care homes for months, I have been struck by common factors with the British abuse scandals: innocent-sounding sailing trips, where children can be isolated and abused, away from prying eyes, then delivered to other abusers; the familiar smearing of whistle-blowers; and the suppression of damning reports.

Jersey social worker Simon Bellwood was sacked early last year after speaking out, and popular health minister Stuart Syvret, 42, was fired in November after publicising the suppressed Sharp Report into abuse allegations.

"The smears on me are water off a duck's back," this brave man told me yesterday in a St Helier cafe. But his hands shook.

I have never assumed that the officials, politicians and police who cover up abuse scandals are all paedophiles, nor does Syvret.

"They just want a quiet life and their competency unquestioned. I'm angrier with them than the abusers, and want several prosecuted for obstructing the course of justice. The police are considering charges," he added.

Traditionally, police fear paedophile ring inquiries as expensive and unproductive. Traumatised witnesses can be hazy and collapse under cross-examination.

Convictions are rare. Police therefore raid suspected abusers for paedophile pornography, which more easily yields convictions.

Well - in theory. In June 1991, police in Cambridgeshire raided the home of Neil Hocquart who abused children in Britain and Guernsey and, with a social worker from Jersey, supplied child pornography for a huge sex ring.

It should have been a major breakthrough. But, as DC Cook told me, it went horribly wrong.

A handful of child sex-ring victims become "recruiters". They are not beaten but rewarded with gifts, money and 'love'. In return, their job is to procure other victims. Such a man, my whistle-blower believed, was Neil Frederick Hocquart.

Hocquart, original surname Foster, was abused while in care in Norfolk and was eventually 'befriended' by an older man, merchant seaman Captain H. Hocquart of Vale, in Guernsey, whose surname he adopted.

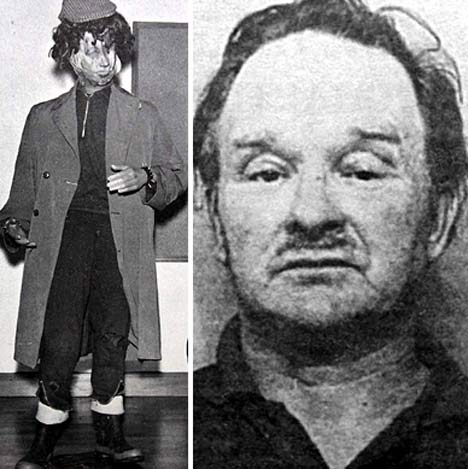

Captain Hocquart was not the only Channel Islands man with an interest in children in care. Satan worshipper Edward Paisnel, "The Beast of Jersey", was given a 30-year sentence in 1971 on 13 counts of raping girls and boys. The building contractor fostered children and played Father Christmas at Haut de la Garenne in the Sixties.

Cambridgeshire police, in a joint operation with Scotland Yard's Obscene Publications Squad (now the Paedophile Unit), raided Neil Hocquart's Swaffham Manor home in June 1991.

They found more than 100 child-sex videos and 300 photographs of children. At nearby Ely they found his friend, Walter Clack, trying to dispose of a sick home video of a middle-aged man abusing a boy.

Who were the children in these films and photos? Police needed properly to question these men. But they never got the chance.

Hocquart secretly took an overdose of anti-depressant dothiepin and died at Addenbrooke's Hospital soon after his arrest. Was his suicide a last act of loyalty?

DC Cook told me incredulously that a senior officer broke with normal procedure and informed Clack, before he was questioned, that the other suspect was dead. Clack then blamed the dead man for everything, and escaped with a £5,000 fine - and inherited one third of Hocquart's wealth, at his bequest.

Wills featured strongly in the fortunesof the Islington and Channel Islands paedophiles. Police discovered that Neil Hocquart inherited his wealth from the Guernsey sea captain.

But Captain Hocquart possibly paid dearly for befriending orphans: he died soon after making out his will in the younger man's favour.

Scotland Yard detectives told me they found at least "two or three" wills of older men who died of apparent heart attacks shortly after leaving everything to Neil Hocquart.

The officers cheerfully called him a "murderer". These deaths were never investigated: the suspect, after all, was now also dead.

Hocquart wasn't the only person in his circle to become rich this way. A Jersey-born friend of Hocquart's, who started his childcare career on the island before becoming a key supplier of children from Islington's care homes to paedophile rings, similarly inherited a fortune.

Nicholas John Rabet was for many years deputy superintendent of Islington council's home at 114 Grosvenor Avenue.

He and a colleague, another single man later barred from social work by the Department of Health, both took children on unauthorised trips to Jersey. Allegations mounted but nothing was done.

Rabet's opportunities to obtain victims massively increased after he befriended the widow of an American oil millionaire. She died after rewriting her will in his favour.

He inherited her manor house at Cross in Hand near Heathfield, Sussex, where he opened a children's activity centre, and regularly invited children in Islington's care to stay.

Hocquart spent £13,000 on quad bikes for the centre, called The Stables, and he and Walter Clack became "volunteers" there.

Hocquart befriended one young boy and took him on a sailing trip, where there would be little risk of being spotted. Police found disturbing film from the trip of men spraying the naked child with water.

But Hocquart left the boy another third of his money, and he denied abuse when questioned.

Police also found at Hocquart's home naked photos of a boy of about ten, whom they learned was in the care of Islington social services. I shall call him Shane.

Sussex police raided Rabet's children's centre. But he had plenty of warning and, they believed, emptied it of child pornography. However officers still found a "shrine to boys", with suggestive photographs everywhere, including pictures of Shane.

They approached Shane, at his Islington children's home. He tearfully confirmed months of abuse. But their attempts to investigate further were thwarted by Islington Council.

Many professionals had, for years, expressed grave fears about Rabet, and put their concerns in writing. But Islington falsely told Sussex officers it had no file material on Rabet or his alleged victim.

Staff had in fact been ordered to find the complaints and deliver them to the office of Lyn Cusack, Islington's assistant director of social services - but they were handed over to Sussex police only when I revealed their existence.

Islington's appalling mishandling of vital records was highlighted by the independent White inquiry into the abuse in Islington children's homes, which found that "at assistant director level . . . many confidential files were destroyed by mistake, although there is no evidence of conspiracy."

During the investigation into Rabet, Islington also refused to interview any other children in care, or, scandalously, help Sussex police identify other children in Rabet's photos.

With only Shane's evidence to rely on, police decided not to prosecute.

I traced Shane. He was furious that Rabet was never prosecuted, but not surprised. "This goes right to the top," he said, "You have no idea how big this is."

He showed me photos of another victim, a young Turkish boy with a sweet shy smile whom Rabet also regularly took from the Islington home to spend weekends at his manor house.

Shane didn't know where the boy was now, he just disappeared. I was never able to find the boy, either. Many children in care are missed by no one.

I retraced Shane two years ago to tell him that justice had finally caught up with Rabet. Third World police had succeeded where Britain's finest in Cambridgeshire, Sussex, London and Jersey had failed.

Rabet fled to Thailand's notorious child sex resort of Pattaya after the White inquiry. He was arrested there in spring 2006 and charged with abusing 30 boys, some as young as six.

Thai police believed he had abused at least 300. But he was never tried: on May 12, 2006, Rabet died of an overdose at the age of 57.

Two other Jersey-born social workers, who for legal reasons I cannot name, also worked in Islington and later with young offenders.

One arranged more of those mysterious sailing trips to Guernsey, the other sent children to Rabet's centre. Both were accused of abuse.

In 1995, we reinvestigated Rabet and met DC Cook at the restaurant. He had gone through Hocquart's papers, investigated other members of the paedophile ring and met their victims. He was horrified at what he discovered.

One man, for example, married a single mother purely so he could abuse her two young sons.

"He told these poor children to keep quiet, that their mother had been lonely so long they would ruin her life if they said anything," the officer told me.

The vicar who married them knew the groom was a paedophile but did not care: he was one too, and got his victims from a British care home.

DC Cook travelled to Guernsey, which Hocquart regularly visited. There local CID officers drove him round, and he met two brothers whom Hocquart abused, then delivered them to a high-ranking, respected local man to rape.

DC Cook traced another distraught victim in England who provided invaluable information about the man, based in Wales, who copied the ring's child pornography for distribution.

This man clearly needed his door kicked in by police, as did Hocquart's other contacts in Britain and the Channel Islands. But no action was taken.

Then word came from on high to drop his inquiries. DC Cook accepted that there might be an innocent explanation - that his local force might not want the financial burden of a national investigation.

But he became deeply troubled when told not to forward his vital intelligence to specialist officers elsewhere.

Britain's new National Criminal Intelligence Squad (NCIS) had the job of disseminating intelligence on paedophiles across the country. Would I, asked the troubled officer, take his information to the squad's Paedophile Unit for him?

And so we pretended to share a meal while I secretly scribbled down the names, addresses, dates of birth and believed victims of dozens of suspects.

My diary records that I met NCIS on January 4, 1996, at 10.30am, and I also channelled the intelligence to Scotland Yard. Neither, unfortunately, had the power to make local forces take action, so I was not optimistic.

This was not the first time I had acted as a go-between. In 1994, another police officer was barred from investigating a paedophile ring, which included an Islington social worker of Channel Islands origin.

We alerted Scotland Yard. This man was, I learned, involved with five overlapping paedophile rings - but he has never been convicted.

Peter Cook has now retired and agreed to go on the record. He told me the partner of Hocquart's video producer was eventually imprisoned for abusing his own sons. "But we could have stopped so much else, so much earlier," he said.

"The news from Jersey is horrifying. I've thought of Rabet all week. The hierarchy does not like these inquiries, they're expensive and produce embarrassment, so people shove it all under the carpet, they don't want to know even when children are dying.

"There will be people now crawling out claiming they were always worried. What cowards, what bastards!"

Jersey police confirmed this week it was aware of Nick Rabet and keen to learn more about his friends. Peter Cook told me: "I will help all I can."

Michael Hames, the former head of Scotland Yard's Obscene Publications Squad, once told me that he never doubted paedophiles were killing children in care.

But the climate of disbelief was fierce, and he asked sadly: "What police chief will dare risk his career by hiring JCBs [to search for the bodies]?"

Courageous Ulsterman Lenny Harper has. Deposed Jersey health minister Stuart Syvret told me: "My family has lived here since William the Conqueror. But if an indigenous police officer were in charge, this investigation would never have happened. Jersey is an oligarchy, where the elite look after each other."

When I flew home late last night, in time for Mother's Day, I felt utter relief.

This tiny island with its high-hedged lanes looked so pretty when the police series Bergerac was filmed here, but to me said just one thing: that there is no escape from here for a terrified child.

If witnesses who want, finally, to help these tragically un-mothered children, now is the time to speak out.

• Historical Abuse Enquiry Team: 0800 7357777

Jersey home dossier to reveal children were murdered...then burnt

Exclusive by Lucy Panton

A SHOCK secret police report into the Jersey House of Hell children's home reveals youngsters there WERE murdered then BURNED in a furnace to COVER UP the atrocities.

captured from the web July 14, 2008

It's feared island authorities may try to hush up the dossier on Haut de la Garenne orphanage but a source told us: "Officers on this case are in NO DOUBT what went on."

Innocent children WERE raped, murdered and their bodies then BURNT in a FURNACE at the Jersey House of Horrors, says a top-secret police report into the scandal.

A News of the World investigation reveals cops have shocking new evidence of how the killings were COVERED UP at the Haut de la Garenne care home.

Our chilling revelations come as officers prepare to hand over their damning dossier from Britain's biggest ever child abuse probe to the island's States of Jersey authorities.

A total of 65 teeth and around 100 charred fragments of bones are all that remain of victims detectives believe were abused and killed before their tortured corpses were thrown into a fiery grave inside the house of hell.

But records of children who stayed at the home over past decades have been destroyed so police have an impossible task of putting names to their grim finds.

A source close to the four-month investigation told us: "There's NO doubt in the minds of the detectives on this case that children WERE murdered in the home.

"Officers believe they have compelling evidence that youngsters' bodies were burnt in the home's furnace then the remains swept into the soil floor in the cellars—the area that became dubbed ‘the torture rooms'.

Ripped

"The problem has been identifying the children that went missing over the years. No records were kept of who came and left that place.

"Kids were shipped to the home from all over the UK and were never heard of again.

"All the inquiry team have to go on is this grim collection of teeth and bone fragments and no names to match up to the remains.

"Because this investigation has seen so many twists and turns people seem to find it hard to accept that children WERE slaughtered and their deaths WERE covered up."

Most of the dental remains discovered have been identified as children's milk teeth. And we can reveal that among more than 100 bone fragments is a TIBIA from a child's leg and what police believe is an "intact" ADENOID bone from the ear of an infant.

These were all retrieved from a fingertip search of the four cellars in the Home's EAST WING.

Forensic teams also found STRANDS OF NYLON which they have concluded came from the head of a broom.

And, because those type of nylon brooms were only used in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the discovery helped officers to put a date on when the bones were swept into the soil floor.

Cops are now convinced that those charred bones and teeth were emptied from the bottom of the home's industrial furnace—located away in the West Wing—when it was ripped out around that time to insall oil-fired central heating.

Officers have spoken to builders who worked on renovations at the home but have been unable to discover what happened to the furnace after that. But they have taken samples from the chimney breast which was left behind.

Around that same time wooden floorboards were laid OVER the old soil floor in the east wing.

And it is there, within the hidden torture chambers just inches below, that the bones, a pair of shackles and children's clothing were found.

Also in the underground rooms police discovered a large concrete bath with traces of blood. A builder has also given evidence that he was asked to dig two lime pits in the ground nearby around that period. Lime pits have often been used to destroy corpses.

So far 97 people have come forward to complain they were abused as children at Haut de la Garenne. Many have described being drugged, shackled, raped, flogged and held in a dark cellar for long periods.

Much of the clothing found at the scene is thought to date back to the 1960s and 1970s when youngsters had to make their own clothes and shoes in the care home work shop.

Cops now believe that whoever was responsible for removing the furnace KNEW that there were children's remains inside. And they think it was moved while disgraced headmaster Colin Tilbrook was in charge of the place.

Tilbrook, now dead, has been described by former charges as being behind "some of the most horrific abuse" at the home.

We can reveal that cops now plan to quiz one of his closest aides who is still alive and living in the UK.

Tilbrook, who ran the home in the 1960s, died aged 62 in 1988 after suffering a heart attack in a public swimming pool. His foster daughter Tina Blee, 38, recently made an emotional visit to Haut de la Garenne to meet abuse victims and bravely told how SHE was raped by the monster every week as a child, after he took her in following his departure from Jersey.

She said: "I needed to come here to say sorry for what he's done. If children were killed here I'm convinced he played a big part in it.

"He was more than capable of murder."

This week police began a forensic examination inside a nearby World War II German bunker which victims say was used as a base for abusing children.

Six witnesses say they were sexually assaulted by staff at the squat brick building which houses a network of underground rooms and passages.

As that work starts, police have closed the doors on their detailed forensic hunt inside the hell home.

Lack of records still hampers police. But we can reveal that one mainland authority, Birmingham City Council, has presented the Jersey force with a list of children who were sent to the home but went missing.

Although four have now been tracked down, after a mammoth search one still remains unaccounted for.

Earlier this year we also uncovered allegations that pictures of BABIES being raped were taken in the care home and circulated by an international child porn ring.

Stash

Experts suspect the home was responsible for many of the seedy network's 9,000 sick pictures, discovered in an infamous haul in Holland in the Nineties.

It was dubbed the Zandvoort stash, after the town where it was found—but the source studio was never uncovered.

Police said their latest intensive probe at Haut de la Garenne has produced more than 40 suspects.

Three men have already been charged with sex abuse offences as part of the inquiry. But now, despite the wealth of shocking detail uncovered by officers, there are fears the full truth about the House of Hell could be covered up yet again after the investigation boss, Jersey's tough No2 top cop Lenny Harper, retires next month.

Haut de la Garenne's abused former residents have repeatedly claimed that what happened was deliberately hushed up to avoid tarnishing Jersey's reputation as a family-friendly tourist haven and to give politicians in London no excuse to try to exercise more control over the island.

Although Jersey is part of the British Isles and under the Queen's rule, it has a separate government system and makes its own laws.

Jersey's 53-member parliament has no political parties and its politicians, judges, policemen and business leaders come from a small elite—often linked by friendship or family.

In a separate case recently investigators were frustrated by the island's legal authorities who refused to charge a couple accused of beating their foster children with cricket bats. Despite being told by lawyers and an honorary police officer who reviewed the case that there was sufficient evidence to go ahead, the charges were blocked at the 11th hour.

A police source said: "The argument for not charging this couple was that their natural children have said they're of good character.

"The detailed statements of all the people who claim they were physically assaulted seem to count for nothing."

The Haut de la Garenne file, along with several others, is now complete but is "being held up" by lawyers.

Our inside source added: "There's a strong suspicion that the files are being held on to until Lenny Harper goes and a new team is in place.

"No one will be surprised if the truth about what happened in the care home never surfaces and once more the evidence gets swept under the carpet."

Source: News of the World (UK)

Remains of five children were deliberately concealed in Jersey home

Jersey police have discovered the remains of five children which were deliberately burnt and concealed at Haut de La Garenne, a former children's home.

By Jessica Salter, Last Updated: 2:38PM BST 31 Jul 2008

Police searching a former children's home in Jersey have found the remains of at least five children.

However officers investigating decades of abuse at the home dating back to the 1960s are unable to tell how or when exactly the children died, making a murder inquiry nearly impossible.

Deputy Chief Officer Lenny Harper, from States of Jersey Police, said there are difficulties dating teeth and bone fragments from the children, who are believed to have been aged between four and 11.

His team have been sifting through 150 tonnes of debris and unearthing pieces "the size of your little fingernail".

He said that while it was possible that the bodies were killed before the 1960s, evidence showed that the bodies were burned and concealed around that time.

"We have the evidence that they were burnt that they were deliberately concealed and that they were moved from one part of the building to another," he told BBC Radio 4.

"You have to ask why would anyone go to the trouble of all that?"

To date, police have recovered a total of 65 milk teeth from the cellars at Haut de la Garenne, but evidence suggests the teeth could only have come out after death.

More than 100 human bone fragments were also found at the site with one piece identified as coming from a child's leg and another from a child's ear.

Tests showed some fragments were cut while others were burnt, suggesting that murders had taken place and the victims' bodies had possibly been cremated in a fireplace.

Police are looking into around 97 allegations of abuse in Jersey dating back to the early 1960s and have said there are more than 100 suspects.

Mr Harper said: "We were pinning our hopes on the process of carbon dating.

"The latest information we're getting is that for the period we're looking at, it's not going to be possible to give us an exact time of death.

"The indications are that if the results come back the same way as they have now it is obvious there won't be a homicide inquiry."

However, the police search has unearthed valuable pieces of evidence which "substantially corroborate" accounts of abuse at the home, Mr Harper said.

Former Jersey health minister Stuart Syvret said that with or without a murder probe it was important to remember the horrendous abuse that occurred.

He said: "I was hoping throughout the whole episode that the police would be able to prove that there had been no child killings.

"I know from speaking to survivors of the appalling abuse that occurred. The abuse aspect was quite appalling enough without children dying.

"But it's very important to try and get across the message that it isn't just the possibility of child deaths that is involved here. There was systematic and monstrous abuse carried out at that institution and others in Jersey."

Investigations started in February after the discovery of what was initially believed to be part of a child's skull.

Tests later suggested it was more likely to be wood or part of a coconut.

Following the find, scores of people came forward claiming they were drugged, raped and beaten.

Police excavated four secret underground chambers at the site, referred to as punishment rooms by some victims, and found shackles, a large bloodstained bath and children's teeth.

In one cellar officers found the disturbing message "I've been bad for years and years" scrawled on a wooden post.

Source: The Daily Telegraph

Home to something evil

What really happened at Haut de la Garenne, the children's home at the centre of the Jersey care scandal last year? Cathy Scott-Clark and Adrian Levy report on a building that still houses some very dark secrets

Cathy Scott-Clark, The Guardian, Saturday 14 March 2009

How Jersey's tourism bosses must have lamented the marketing slogan they chose last year: "Small enough to really get to know, yet still big enough to surprise."

It was supposed to mark a campaign to rejuvenate the holiday business.

Instead, it served to highlight a child abuse scandal that erupted on the island.

The story had first trickled out in November 2007, gaining almost no press attention. Following a covert police inquiry into allegations of mistreatment in the island's care homes, police and the NSPCC in London had appealed to former residents to come forward. By January 2008, hundreds were said to have made contact, reporting physical and sexual abuse, mostly at Haut de la Garenne, a grim, Victorian industrial school that had, until the mid-80s, served as Jersey's main children's home. Soon, Jersey was in the grip of one of the largest police child abuse inquiries seen anywhere in Britain.

How would the tiny island and its 88,000 residents hold up? They pride themselves on their traditionalism (the pound note survives here) and an independent spirit that locals refer to as the Jersey Way. The mantra, reflecting a closed community that knows how to look after itself, is credited with transforming the place from a bourgeois bucket-and-spade resort in the 50s into the oyster-shucking tax haven it is today. So potent is the lure of the island's low-tax, non-intrusive regime that the level of wealth required of prospective settlers has risen to stratospheric levels: only those who can pay a residency fee of about £1m and show assets in excess of £20m need apply. The lucky few include racing driver Nigel Mansell, golfer Ian Woosnam, broadcaster Alan Whicker and writer Jack Higgins, as well as hundreds of reclusive tycoons, who have made the island the third richest compact community in the world, after Bermuda and Luxembourg.

And then February 2008 arrived like a fist in the face. All anyone on the outside looking in could talk about was paedophiles. Then Jersey police announced they were investigating murder as well as complaints of physical and sexual abuse: witnesses said they recalled seeing the corpses of children at Haut de la Garenne; others claimed to have found bones buried beneath the foundations.

What made it worse for those on the inside was that the crisis had been started by an outsider, a Northern Irish copper called Lenny Harper, second-in-command of the island's police force, and the antithesis of the Jersey Way. Instead of managing bad news, Harper had teams of forensics specialists excavating for it. Every day, sitting on a granite wall outside the home, Harper regaled the world's press with stories that "something evil" had happened there - Haut de la Garenne had been a virtual charnel house. The first find was a sliver of human skull on 23 February. As the investigation progressed, the supposed tally rose to "six or more" bodies buried beneath the home.

By August last year, Harper had retired, to be replaced by a new policeman from the British mainland. More experienced than Harper, detective superintendent Mick Gradwell was a veteran whose cases included the deaths of 23 Chinese cockle-pickers at Morecambe Bay in 2004.

At his first press conference, on 12 November, Gladwell stunned reporters with his findings: "There were no bodies, no dead children, no credible allegations of murder and no suspects for murder." Only three bone fragments could be definitely said to be human, he said - and they dated from the 14th to 17th centuries. Newspapers ran gleeful headlines: "Lenny Harper lost the plot." By the time we arrived on Jersey in February 2009, a year after the digging had begun, it was as if Harper and his inquiry had never existed.

The Jersey establishment was triumphant. One of the island's most senior social workers expressed a view we were to hear many times: "I'm not saying all the former children's home residents are liars but some have misremembered," he said. "Some have embellished and a small number have been telling porkies to get money." Nothing was wrong with the island. Jersey was off the hook. It was all a cock-up.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

Among the thousands of statements that still line the shelves of Harper's old incident room, and in the testimony of former residents and workers at Haut de la Garenne and other institutions across Jersey, many of whom we tracked down and interviewed, harrowing stories are buried.

Over a period of three decades, residents of the care homes made repeated complaints that they were being sexually and physically abused. A series of damning reports was produced, following confidential inquiries into these institutions, most of which went unheeded. Few prosecutions ensued.

It is true to say there were no corpses. However, the testimony provides compelling evidence of a catastrophic failure within Jersey's children's services that ran a regime so punitive, they preferred to lock up problem children en masse than deal with them in their own homes: four times more children, proportionately, are imprisoned in Jersey than in its nearest neighbour, France. And what happened to them once in care was something that Harper's team, had they not been distracted by murder plots, came close to exposing.

Harper clashed with the Jersey Way as soon as he was appointed head of police operations in 2002. A career officer, he had been office-bound for a few years and on Jersey he wanted to get back to real policing. Summing him up, one former Jersey colleague told us that Harper "was a bit of a pit bull" who found himself on a small island where discretion and subtlety were valued above all else. Early attempts at making his mark, including a clear-out of illegally held weapons and a curtailment of the often cosy relationship between local police and businessmen, made him instant enemies. Harper, who now lives in Ayrshire, told us: "I started getting death threats. But I'd been on the streets of Northern Ireland."

His most significant problem was recognising the limits of his power. Jerseymen trace their ancestry back to the medieval Dukedom of Normandy and a feudal culture survives. The island is divided into 12 parishes, each governed by a connétable or head constable, who between them raise a private volunteer police force, the Honorary Constabulary. It might sound like a toytown operation, but these so-called "hobby bobbies" form a network of neighbours, friends and relatives licensed to arrest and charge fellow islanders through powers vested in them by the 500-year-old States Assembly.

The assembly - made up of the connétables, their deputies and 12 elected senators, many of them multimillionaires - is supervised by the bailiff, Jersey's highest officer, who is appointed by the Queen, while the task of upholding the law and keeping the hobby bobbies in check falls to the attorney general. These two key posts are currently held by brothers, Sir Philip and William Bailhache, members of one of the oldest and most powerful families on Jersey. At the bottom of the heap are the 240 officers of the States of Jersey Police, imposed on the island in the 50s but even today requiring attorney general Bailhache's approval to charge anyone with anything more serious than a traffic citation.

It was a system that frustrated newcomer Lenny Harper, until he found an ally inside the attorney general's office. This was a mainlander who similarly mistrusted the Jersey Way and told Harper of a "web of child abusers" who he claimed all knew each other. He also alleged the attorney general's office appeared reluctant to prosecute. When we put this to William Bailhache, he replied that Harper had repeatedly suggested his office was "soft" on child abuse - this is untrue, he says, and so is the suggestion that he was reluctant to prosecute. "I have signed many indictments for people charged with child abuse offences, some of them historic. Several cases have resulted in substantial sentences of imprisonment."

Harper recalls: "I was cautious at first. The allegations reached into many worthy organisations, including the Sea Cadets and the St John Ambulance, and there were whispers about establishment men. One name that kept cropping up was Paul Every, a commanding officer in the island's Sea Cadets." Every had also served as a senior civil servant.

Harper dug around, discovering that Every's name had surfaced in connection with child porn offences during Operation Ore in 1999. In late 2004, Harper applied for a warrant to search the Sea Cadets' HQ. He was refused. Harper then contacted the Jersey Sea Cadets directly: "They completely ignored me and refused to sack Every." When the States Assembly, too, declined to act, and Harper received a message from the attorney general's office that it was reluctant to prosecute, Harper began to suspect a cover-up. He says, "What made things more fraught was that some of my own officers were in the Sea Cadets." (On this case, the attorney general comments: "It is absolutely not the case that I decided not to prosecute Every. It is true that one of my officials wrongly gave Mr Harper that impression.")

Harper pressed on, and in January 2005 had Every arrested and his home computer seized. On it, police recovered a cache of child porn and evidence that Every had scoured the internet for "naked sea cadets". Still unable to persuade the local Sea Cadets to act, Harper wrote in August 2005 to the youth organisation's national HQ in London, and finally Every was removed from his position. The following month, Harper arrested Roger James Picton, another Sea Cadet volunteer; Picton was found guilty of indecent assault on a schoolgirl in February 2006 and Every was convicted of child porn offences that December.

In early 2007, convinced there was a broad network of abusers operating on the island and mindful of Jersey's steadfast refusal to introduce a sex offenders' register, Harper began reviewing statements made by Sea Cadets who had alleged abuse. He discovered that many had been in care, especially in Haut de la Garenne. Calling up their care files, Harper found that a member of Jersey police's family protection team, Brian Carter, had been there before him. Carter was no longer in the force, but finding him on the island was easy. It turned out that in 2004 Carter had noticed an unusually high incidence of suicide among men who had passed through Haut de la Garenne. Reviewing the records of 950 former residents, he discovered that a significant number had complained of sexual and physical abuse, describing similar acts and perpetrators, going back to the 50s. Shockingly, even though supervisors at the homes had dutifully noted the complaints, none had been properly investigated.

Carter had sought out victims and taken statements detailing how they were allegedly beaten and raped by older children and staff, and also by Sea Cadet officers, St John Ambulance volunteers and at least one senator in the States Assembly. In April 2006, Carter handed the dossier to Jersey CID. Nothing happened.

Suspecting that allegations of crimes against hundreds of children were being brushed under the carpet, Carter quit the force in late 2006. Now, Harper alerted Graham Power, head of Jersey's police, to the dossier. Appalled, Power contacted the Association of Chief Police Officers which launched an independent inquiry, currently being handled by South Yorkshire. In September 2007, Power gave Harper the go-ahead to launch a full-scale child abuse investigation, with Carter re-employed as a civilian investigator. Together they set up an incident room at Jersey police headquarters in Rouge Bouillon, St Helier. Detective inspector Alison Fossey, another outsider, originally from Strathclyde, was called in to help sift through the first of 4,000 children's files.

Abuse claims were rife. Haut de la Garenne was at the centre; other child facilities on the island were also implicated, including a secure unit called Les Chenes and a "group home", Blanche Pierre. Harper ordered his men to find and interview as many victims as they could - something that proved difficult because several former care home residents had already spoken to Carter and were disillusioned when nothing came of it.

Fearful that his inquiry would collapse, it was then that Harper went public, making an appeal for witnesses to come forward, with the backing of the NSPCC. "I was summoned to the chief minister's office and given a rollicking," Harper claims. "CM Frank Walker told me, 'Stop calling these people victims. It's not proven yet. You can't say that. Do you realise what you are doing here can bring the government down?' " We tried to contact Walker, but he declined to respond.

A firestorm now swirled across the island. Harper recalls: "The NSPCC opened a helpline and the phones went haywire." Former Haut residents talked of being slammed into walls, punched and slapped. One victim from Les Chenes claimed to have been knocked out by a staff member and told police, "The supervisor put a foot on my chest and stood on me, screaming, 'This is what we do to scum like you!' " Former care home children also detailed sadistic sexual abuse, with residents raping their dorm mates and supervisors doing the same.

Dozens of potential protagonists were thrown up by the new inquiry, the same names having also been identified by victims in the Carter report. One of them, a former Jersey senator, Wilfred Krichefski, who died in 1974, was known as the "Fat Man" among Haut residents who accused him of multiple rapes. Other Haut victims claimed to have been "lent out" to men who took them sailing into international waters before forcing them to have sex - crimes thus committed outside Jersey's jurisdiction. Colin Tilbrook, a former headmaster at Haut de la Garenne in the 60s, was repeatedly named as having roamed the corridors at night with a pillow tucked under his arm with which to stifle the screams of the children he raped. Jersey social services had never investigated Tilbrook, who went on to secure a job in the early 70s on the British mainland. When news of the Jersey investigation became public, Tilbrook's foster daughter, by then in her 30s, came forward to reveal that he had repeatedly raped her when she was a child.

Like Krichefski, Tilbrook was dead, as were others accused, including Jim Thomson, the superintendent of Haut de la Garenne in 1979, who was repeatedly accused of abuse. It was the living that presented Harper's team with the knottiest problems. The list of those who had worked at the homes included the serving education director, Tom McKeon, and his deputy, Mario Lundy. Both were interviewed by police earlier this year; both vigorously deny any wrongdoing.

The inquiry was delivered a blow when, in January 2008, Harper's deputy, DI Alison Fossey, went to the mainland on a strategic command course. Fossey had a law degree and had worked in child protection for most of her career. She was a details person, while Harper had a more scattergun approach. In her absence, the investigation was transformed by lurid claims of bodies and murder. One police report from this time states, "Among the [Haut] victims were a few who said that children had been dragged from their beds at night screaming and had then disappeared." A local builder who had done renovations there in 2003 said he had found what he thought were children's bones and shoes. These items had been disposed of by the Jersey pathologist. Harper remained suspicious. On 5 February 2008, he flew to Oxford to take advice from LGC Forensics, a crime scene service used by forces across the UK.

Two weeks later, an LGC team encamped at Haut de la Garenne. A squad of technicians in white suits pored over the site. Central to it all were two sniffer dogs, Eddie and Keela, which Harper took to describing as his "canine assets". They were veterans deployed in the search for missing Madeleine McCann in Portugal, although the controversy caused there should have served as a warning to Harper. In Portugal, the dogs had crawled over a car used by Gerry and Kate McCann, and sounded the alarm. The Portuguese police then claimed that the McCanns had killed their daughter, when what the dogs had actually picked up on was both parents' legitimate proximity to death, working in hospitals.

At Haut de la Garenne, the dogs made straight for the place where in 2003 the builder said he had found bones. A senior police officer recalled, "They did cartwheels on the spot. And Harper went through the roof." As in Portugal, the dogs had smelled something but could not differentiate between ancient remains and a contemporary murder. But at 2pm on 23 February, caution cast aside, Harper called a press conference, telling reporters police believed that the partial remains of a child were buried there.

Over the following months, £7.5m would be spent sifting 100 tonnes of earth. By the time DI Fossey returned, there were 65 milk teeth, 165 bone fragments and two lime-lined pits dominating the inquiry.

Meanwhile the child abuse investigation, which had already identified 160 alleged victims, was, Harper claimed, taking flak. Harper was called to the attorney general's office after his team charged a former Haut warder with indecently assaulting underage girls at the home from 1969 to 1973. William Bailhache demanded that a lawyer appointed by his office be inserted into the inquiry to assess the evidence before any arrest or charges could be preferred - common practice on the mainland, he says.

The police sent the lawyer details of a further five suspects, including a former police officer and two couples. Hearing nothing for two months, Harper went ahead and arrested the 50-year-old former police officer on 12 June last year. The attorney general's lawyer had the man released the next day, citing a lack of evidence. Likewise he vetoed charges being laid against one of the two couples. That left only Jane and Alan Maguire, a couple now living in France, and their case, too, went nowhere.

Bailhache told us: "It would no doubt have been much easier for me personally if I had simply waved prosecutions through. However, had I done so I would have been failing in my duty... Actions on my part which Mr Harper no doubt interpreted as frustrating a prosecution were rather directed at ensuring that any prosecution which was properly brought had the best chance of succeeding."

In the end, Harper charged only two other individuals, both peripheral, one of whom, in a terrible irony, also claims to have been a child victim of abuse at Haut de la Garenne in the 70s.

Once Lenny Harper retired in August 2008, and the murder inquiry was discredited, some island officials were concerned that the investigation into the abuse allegations might collapse, too.

The alarm had been raised in 1979, following the death of a two-year-old at the hands of a foster parent. Two years later, visiting social workers David Lambert and Elizabeth Wilkinson, concerned that none of the proposed improvements had been put in place, launched a full-blown inspection. Their confidential report, taking a broader look at Jersey society, concluded that while the island was reinventing itself as a haunt for jetsetters, there was a neglected group afflicted by a "high incidence of marital breakdown, heavy drinking, alcoholism and psychiatric illness". These problems were exacerbated by a small island mentality that demanded everyone "conform to acceptable public standards".

Children rebelled in small ways: dropping litter, swearing, facing down the police, having parties on the beach. On Jersey, all of these "offences" were, according to Lambert and Wilkinson, often sufficient to get a child into serious trouble. And once children had come to the attention of the police, it was almost inevitable that they would enter Jersey's care home system. Without any provision for children to be bailed, most were incarcerated on remand, placed alongside children taken from their families, often for such reasons as "giving the mother a break". In this rural backwater, one in 10 children had been in care, a ratio far higher than on the mainland.

Once in care, the real problems began, with predatory residents, some with criminal records, bunked with the vulnerable. Cases were almost never reviewed; Lambert and Wilkinson found in one group of 65 children, 36 had remained invisible inside the system for more than 10 years. This was the more likely if parents made little fuss, or even, in some cases, left the island. One of the invisible told us how he had been incarcerated at Haut de la Garenne for being repeatedly sarcastic to the hobby bobbies; he stayed in care for eight years, he says, without ever seeing a trained social worker, during which time he claimed to have been raped by adults and fellow inmates alike.

At the time of Lambert and Wilkinson's visit, Haut was run by superintendent Jim Thomson. Like many then working in the Jersey care system, he had no professional qualifications. Thomson, who would be accused of sexual and physical abuse in Harper's 2008 inquiry, was found by Lambert and Wilkinson to have created a "highly unsatisfactory" environment that focused on corporal punishment for "boys aged 10 to 15", some of them locked in remand cells for days at a time. It was an institution ripe for abusers, especially at night when only one staff member was on duty for 45 children sleeping in four distant wings. Haut was "not suitable for any of the tasks in which it is currently engaged".

Nick (not his real name) was resident at the time. He told us he had been taken, aged 11, to Haut de la Garenne in "a large white van with bars on its windows" after his mother abandoned him in 1975. He said: "The dorm was at the end of a rabbit warren of corridors and consisted of eight hospital-style beds lined up against opposite walls. Most of the boys were in their teens and had been in the home for years." No sooner had he arrived than he was beaten up and his possessions stolen. "At night they would never come to check up on you. The younger boys would be tied down on their beds and raped by the older lads." He survived only because he was a boxer and he was allowed to stay with foster parents at weekends, a time when adults were said to come and prey on the children left behind.

According to the 1981 report, other homes caused concern, too, for their punitive regimes; chief among them was Blanche Pierre with its new house parents, Jane and "Big Al" Maguire. But the extent of the allegations against the Maguires would not be properly investigated for another 18 years. One of their former charges was Dannie Jarman, now 28, who moved into Blanche Pierre when her mother was diagnosed with cancer in 1985, ending up in a hospice. "I wasn't allowed to visit her," Dannie told us. "Two weeks after her funeral, I was told she was dead. I was repeatedly told that our mum hadn't brought us up right and had never wanted me." Other children later levelled accusations about the extremely harsh conditions.

No one would have known about it had Dannie Jarman not got drunk one night in 1998 and thrown a brick through the Maguires' bedroom window. When the Maguires called the police, former residents, including Dannie, were brought in for questioning. After they repeated their allegations of abuse, the police turned around their inquiry and charged the Maguires instead.

The then attorney general, Michael Birt, today the island's deputy bailiff, sought advice from counsel who suggested that while this home "might possibly have been one that was run on a somewhat Dickensian basis, the strict regime applied by the Maguires would have not been regarded as unusual in pre-politically correct times. Indeed it is quite likely members of the jury would have some sympathy for people who in order to instil a sense of discipline in their charges threaten to wash a child's mouth out with soap and water." The counsel suggested: "The evidence is extremely weak." Birt, who declined to comment when we approached him, dropped the charges. Following an internal inquiry, Jane Maguire was subsequently sacked by Jersey social services.

Another inquiry focused on Jersey's elite Victoria College after the head of maths was jailed for four years in April 1999 for indecently assaulting a pupil. In his report, Stephen Sharp, a former chief education officer for Buckinghamshire, criticised senior staff and school governors, who included bailiff Sir Philip Bailhache, for failing to act speedily or adequately. It had taken 15 years for the teacher to be caught and Sharp concluded: "The handling of the complaint was more consistent with protecting a member of staff and the college's reputation than safeguarding the best interests of pupils."

Haut de la Garenne eventually closed in 1986, Blanche Pierre in 2001, but when Kathie Bull, a British child behaviour expert, was called in the following year to inspect the island's children's services, she found the situation had worsened. So many children were now being locked up that the island's institutions operated a "hot-bedding" system to cater for them, which in the case of Les Chenes included children sleeping on a pool table. Discipline was meted out in The Pits, a punishment block consisting of four bare concrete cells. The island's youth justice system was backwards and brutal, Bull concluded, and she made 50 recommendations, including the establishment of a Children's Executive.

Four years later, when Simon Bellwood, a British social worker, was employed to close Les Chenes and move the secure unit to a new, purpose-built site, he was startled to find the old regime still in force: "I met children who spent months at a time, near naked, in bare, concrete punishment blocks." When he made public his concerns in 2007 - following a long-running dispute with some of the old regime who were still in positions of authority - he was sacked; the then health minister, senator Stuart Syvret, who had vocally championed those who alleged they had been abused, was voted out of office for his "intemperate and ill-considered statements in the assembly".

Two years on, Mick Gradwell's team is trying to pick up the pieces of the abuse inquiry. The attorney general has been handed evidential files against key suspects by the police, and says he expects to make his decisions in the next few weeks. Bellwood, Syvret and others are keeping up the pressure on Jersey's States Assembly, and lobbying UK justice minister Jack Straw to call a full, independent inquiry (the subject of a court hearing to be held in London next Tuesday). But, many of the victims of the care homes of Jersey are convinced that nothing can outflank an island establishment that often saw little wrong in what had gone before and is reluctant to embrace the future prescribed by the social work experts.

The guardians of the Jersey Way continue to thrive, such as the sprightly Iris Le Feuvre, elected to the States Assembly for almost 20 years, who as president of the education committee oversaw Haut de la Garenne, Les Chenes and Blanche Pierre during some of their most troubled times. Now retired, the 80-year-old, whose husband Eric was for years a hobby bobby, lives in St Lawrence parish. "Granny's coming," she shouts as an over-excitable Tibetan spaniel barks at the gate, and ushers us into her front room. Le Feuvre, who collected an MBE from Buckingham Palace in 2002, says of Haut de la Garenne: "It's been a terrible business. But mostly I feel for William and Sir Philip Bailhache. They've been through so much."

But what of the victims? She smiles: "Oh, such a fuss has been made. My father always used a belt on me. It did me the world of good."

Source: Guardian

Was the Jersey probe a witch hunt that was stopped by higher authority, or a case of real abuse subject to a cover-up? The following story supports the cover-up version.

BBC NEWS

Senator released over data breach

A Jersey States politician arrested in connection with allegations of breaching data protection laws has been released pending further inquiries.

Police arrested 43-year-old Senator Stuart Syvret at an address in Grouville shortly after 0900 BST.

The senator and former health minister is thought to have spent six hours in custody helping police with inquiries.

A Jersey Police spokeswoman confirmed that a 43-year-old man was released on Monday afternoon.

Inquiry call

Senator Syvret was an outspoken critic of the States of Jersey and the handling of the police investigation in the island into claims of child abuse from the 1960s to 1980s.

In 2007 he was dismissed from his post as Minister for Health and Social Services after claiming abuse cases were being covered up.

The investigation focused on the former Haut de la Garenne children's home.

Hundreds of ex-residents contacted detectives with details of alleged sexual and violent assaults.

Senator Syvret, who called for both an independent inquiry and for court cases to be held on the UK mainland, was accused by the Chief Minister, Frank Walker, of damaging Jersey's reputation.

Source: BBC

Angus couple guilty of Jersey child abuse

A couple who were working at Haut De La Garenne care home have been found guilty of eight counts of abuse each.

An Angus couple accused of child abuse offences at a Jersey care home have been found guilty.

Anthony Jordan, 62, and his wife Morag were found guilty of eight counts of abusing children each. Judge Sir Christopher Pitchers delivered the verdict on Friday.

Mr Jordon of Brechin Road, Kirriemuir, was found guilty of abusing children at the Haut de la Garenne children’s home on the island between 1981 and 1984.

His wife Morag, originally from Dundee, was employed at the house between 1970 and 1984. She was also found guilty of eight counts of common assault during her work there, including shoving soap into their mouths and pushed the face of one into a puddle of urine.

The charges relate to offences committed against 11 children aged between one and 17.

The jury of six men and six women heard from a succession of witnesses before retiring to reach their verdict. The Royal Court in Jersey heard from former residents, now all in their 40s, giving evidence that Jordan and his wife Morag abused them.

The couple, who were arrested in February 2010, worked at the centre until 1984. Sentencing was deferred until January 6.

Source: STV, Scotland